eBook - ePub

Internal Displacement

Conceptualization and its Consequences

Thomas G. Weiss, David A. Korn

This is a test

Share book

- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Internal Displacement

Conceptualization and its Consequences

Thomas G. Weiss, David A. Korn

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This new volume traces the normative, legal, institutional, and political responses to the challenges of assisting and protecting internally displaced persons (IDPs).

The crisis of IDPs was first confronted in the 1980s, and the problems of those suffering from this type of forced migration has grown continually since then. Drawing on official and confidential documents as well as interviews with leading personalities, Internal Displacement provides an unparalleled analysis of this important issue and includes:

- an exploration of the phenomenon of internal displacement and of policy research about it

- a review of efforts to increase awareness about the plight of IDPs and the development of a legal framework to protect them

- a 'behind-the-scenes' look at the creation and evolution of the mandate of the Representative of the Secretary-General on IDPs

- avariety of case studies illustrating the difficulties in overcoming the operational shortcomings within the UN system

- aforeword by former UN high commissioner for refugees, Sadako Ogata.

-

Internal Displacement will appeal to students and scholars with interests in war and peace, forced migration, human rights and global governance.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Internal Displacement an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Internal Displacement by Thomas G. Weiss, David A. Korn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Política. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Putting the issue on the map

Resolution 1992/73, which the 53-member United Nations Commission on Human Rights approved on 5 March 1992 near the close of its annual session in Geneva’s stately Palais des Nations, did not seem like a ground-breaking initiative. It called for the secretary-general to:

Designate a representative to seek again views and information from all Governments on the human rights issues related to internally displaced persons, including an examination of existing international human rights, humanitarian and refugee law and standards and their applicability to the protection of and relief assistance to internally displaced persons.

One year earlier the commission had asked the previous secretary-general to prepare “an analytical report” on IDPs. That report, issued in the name of newly appointed Boutros Boutros-Ghali in February 1992, concluded with a call for the establishment of a “focal point” (in UN jargon, a person or an institution with responsibility for an issue) within the human rights system for internally displaced persons.1

The phenomenon of internal displacement was real enough. Around the globe millions of people were being forced from their homes by a spreading rash of state breakdowns, civil wars, and other violent disorders, with no assured access to international humanitarian relief and even less prospect of international protection from the worst sorts of abuses. Was a study all that the UN’s main human rights body could think of? A look to the history of the UN’s handling of refugees provides insights for an answer.

At its close, the Second World War left tens of millions uprooted in Europe and Asia. The vast majority had fled across borders for sanctuary while others who could not or did not wish to escape remained within the boundaries of their home countries. The Cold War followed and had a different effect. Refugees continued to play a prominent role as political pawns, fleeing from the East to the West where they were granted asylum, in part to make a political statement. Meanwhile, geopolitical competition between the two superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, led to the channeling of massive economic and arms assistance to client Third World regimes, which assured a fragile artificial stability in many parts of the globe for much of the Cold War.

Victims of persecution who crossed frontiers fell under the 1951 Convention on Refugees. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees was specifically charged to assist and protect them. Those who remained within their home state, however, were far harder to help. Given the international system’s prevailing norms, outsider access to victims required permission from the very authorities who were abusing them. Human rights groups, both intergovernmental and nongovernmental, confronted the traditional bulwark, state sovereignty and its corollary principle, nonintervention in domestic affairs.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the accompanying civil war was soon followed by the eruption of internal armed conflicts in southern Africa (in Mozambique and Angola) and in Central America (in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala). Beginning in the early 1980s, these wars prompted a dramatic rise in the numbers of displaced. But this time, the proxy wars in the East–West conflict meant that most of those forcefully uprooted were IDPs rather than refugees.

As the grip of the Cold War loosened, and particularly after its end, fewer political points could be scored by accepting refugees, especially when so many came from the poorest of countries instead of Eastern Europe. Asylum regimes tightened as “the end of the Cold War swept away any remaining ideological motive for accepting refugees.”2 Hence, both the nature of the wars and the politics of asylum changed. Refugee numbers diminished while IDPs shot up still further. As the superpowers abandoned Africa in the 1990s and were no longer jockeying in an ideological war, stability crumbled; refugee numbers continued to fall, but IDP numbers continued to increase.

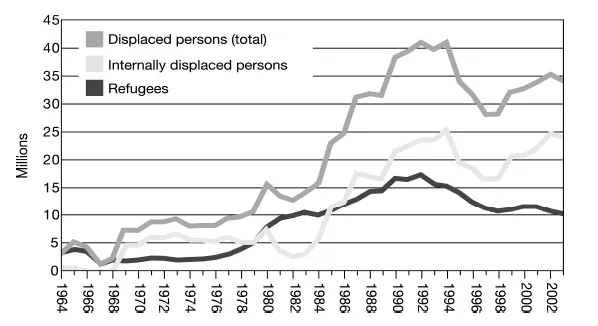

There are a number of explanations for the dramatic rise of internally displaced persons. The nature of warfare changed, as belligerents directly targeted civilians, and brutal ethnic cleansing left returning refugees without secure homes. Moreover, not only was the phenomenon of internal displacement better understood than a decade earlier, but better data also were available. If we fast forward to the present, statistics indicate that the ratio of IDPs to refugees is 2.5:1, as depicted in Figure 1.1. Some recent research also suggests that refugee flows may be greater in the face of state-sponsored genocide than civil wars; and that refugee numbers (relative to IDPs) will be greater if armed conflict occurs in a country whose neighbors are relatively wealthy and democratic rather than poor and authoritarian.3

Figure 1.1 IDPs and refugees, 1964–2003.

Source: Andrew Mack, ed., Human Security Report 2005 (Vancouver: Human Security Centre, 2005), 103.

Statistics are one thing, but what was the actual meaning for a war victim who fell into this category? If someone fled across an international border seeking safety from persecution, she or he could qualify for refugee status and for international assistance and protection under the 1951 Refugee Convention, the implementing arm of which is the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, headquartered in Geneva, with 5,000 strong and an annual budget of $1 billion. But if that same individual stopped short of crossing an international border, the hope for succor and protection would be non-existent from the home government, which in most cases either was the oppressor or had no means to help. If that person were lucky, UNHCR might have an extra tent and food if the IDP happened to mingle with a refugee population from another armed conflict, or if it was one of those special situations in which the secretary-general, Security Council, or General Assembly specifically asked UNHCR to help the internally displaced. If it happened to be on the scene, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) might also offer help.

But there was and still is no internationally accredited agency with a mandate to reach inside state borders—overriding state sovereignty in the process—to assist and protect internally displaced persons in any and all circumstances. What in 1982 had been a minor institutional lacuna, at least in terms of numbers, had become within less than a few years a glaring hole in the international safety net for victims of armed conflicts.

Journalists hate the term and the acronym. “Internally displaced persons” is an awkward mouthful, and “IDP” lacks pizzazz and offers no immediate clarity of meaning for those seeking sound-bites rather than writing legal treatises. For years reporters and editors were reluctant to use it. An outspoken Richard Holbrooke called it “odious terminology.”4 He and others preferred anything, even a circumlocution, or calling the internally displaced “internal refugees,” or, inaccurately, simply “refugees.” Even those in humanitarian and human rights organizations as well as other professionals working on uprooted people do not much like it. For instance, a special issue on Africa in National Geographic in September 2005 contained the following: “Number of refugees: 15 million—3.3 million who have fled their native countries because of conflict, some 12 million who are internally displaced.”5

“Refugees” immediately evokes the image of people fleeing persecution. “Internally displaced persons” is too many words, too clinical, too antiseptic. It does not automatically conjure up any identifiable image of distress. It does not convey the fact that in many instances these people are the most destitute of the destitute, those most exposed to hunger and disease and abuse by governments and rebel movements, the populations with the highest death rates recorded among all those whom humanitarians seek to assist. Or that they are, in their overwhelming majority, women and children, the most vulnerable of the vulnerable.

Try as they might, neither journalists nor others could come up with anything more concise or evocative that did not blur the line between people uprooted inside their own country and those who had crossed a border. “Internally displaced persons,” soon shorthanded to “IDPs,” became the term of art. Interestingly, in the wake of the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in August and September 2005, the term “displacees” became commonplace after African-Americans reacted negatively to being labeled “refugees” and the implication that somehow they were the “other.” The acronym “IDP” suddenly was not something relegated to the documents of UN organizations or private charities working in Africa but quite pertinent for the American South. Perhaps there would be room to adopt “displacees” as the alternative—it has the same number of syllables and rhymes with “refugees.”

The first substantial institution to make a public issue of how the numbers of internally displaced persons had burgeoned was the United States Committee for Refugees, a Washington-based private voluntary organization that issues an annual worldwide refugee survey. In its 1982 accounting, USCR estimated a total of 1.2 million persons in “refugeelike situations” within their own countries.6 By 1985 USCR was recording such a surge in the number of internally displaced—to over 9 million—that it decided to establish a distinct reporting category for them. By 1987 the 15 million mark had been crossed, about the same as refugees; and by 1992 the number of internally displaced persons from wars was edging toward 25 million, surpassing the figure for refugees. The report of the Independent Commission on International Humanitarian Issues, chaired by two princes—former UN high commissioner for refugees Sadruddin Aga Khan and Jordan’s then crown prince Hassan Bin Talal—also contained a significant treatment of the phenomenon in its examination of the “uprooted.”7

Well before that, however, the sheer numbers of the internally displaced had brought to light the fact that neither the UN’s elaborate humanitarian assistance machinery nor its more limited human rights apparatus had institutional arrangements for their assistance or protection. A UN-sponsored Conference on the Plight of Refugees, Returnees and Displaced Persons in Southern Africa, held in Oslo in August 1988, was the first to draw attention officially to this gap in the UN system.8 The conference proceedings prompted a resolution in the General Assembly in the fall of that year, calling on Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar to study the need for an international mechanism to coordinate relief programs for the internally displaced. He did not welcome the initiative. In a report issued in 1989, Pérez de Cuéllar replied that he did “not believe it necessary or appropriate to establish a new mechanism or arrangement to ensure the implementation or overall coordination of relief programs to internally displaced persons.”9 He nevertheless designated United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) resident representatives, in their capacities as UN resident coordinators, to be “focal points” for coordinating relief for internally displaced populations in the countries to which they were assigned.

The step was important symbolically as an acknowledgment of the need for the UN to gear up to deal with the challenge of internal displacement, but its immediate practical effect was negligible. The resident representatives’ line of work was economic development, not humanitarian assistance. Not only did few have humanitarian experience, they had no authority to initiate actions to assist the internally displaced, and the secretary-general’s designation of them as “focal points” gave them none; they had to wait for governments to ask for help. And they had no authority whatsoever to act to protect the internally displaced from killing and other abuses that governments and insurgent movements frequently inflicted. Perhaps most importantly, drawing the attention of governments to human rights abuses was awkward, to say the least. It would have impeded the kind of good diplomatic relations on which UNDP technical cooperation depends. In short, it was not in the bureaucratic interests of officials based within a country even to raise the issue.

Still, Pérez de Cuéllar’s instruction kept the subject alive. It nudged the UNDP’s Governing Council to ask, in June 1990, for a survey of the UN system’s ability to assist refugees, displaced persons, and returnees. That request in turn generated a resolution in the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) the following month asking the secretary-general for a survey of the UN system to “assess the experience and capacity of various organizations in assisting all categories of refugees, displaced persons and returnees.”10 Jacques Cuénod, a recently retired UNHCR official, was hired. His 1991 report concluded by recognizing the obvious reality that “within the United Nations system there is no entity entrusted with the responsibility of ensuring that aid is provided to needy internally displaced persons.”11 The problem, Cuénod wrote, was the lack of international protection:

Assistance to internally displaced persons raises delicate issues for the United Nations system which has to respect the national sovereignty of its members. In some situations, an offer of assistance by the United Nations may be interpreted as an interference in the internal affairs of the State or an implicit judgment on the way some nationals have been treated or not protected by their Government. The Secretary General has little room to act because the United Nations Charter recognizes explicitly the concept of domestic jurisdiction in its Article 2(7).12

Humanitarian and human rights advocates hoped, somewhat prematurely as it turned out, that the Security Council’s authorization for U.S. and allied intervention in Iraq to protect the Kurds, in the spring of 1991, would mark a turning point, a breach that would show the way to shake off the shibboleth of state sovereignty when large numbers of persons were at risk.13 Even earlier, in 1989, Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) had established a precedent for UN action to provide food and medicine for displaced persons, albeit in that instance with reluctant agreement from Khartoum.14 Nonetheless, governments remained hesitant to challenge the notion that state sovereignty in most instances barred the United Nations from assisting people uprooted and abused within their own countries. When France proposed, in ECOSOC, a right of intervention in humanitarian crises, the resolution failed.

In the end, nongovernmental organizations would push the issue of internal displacement onto the agenda at the UN’s Commission on Human Rights. By the 1980s, NGOs had become a powerful force both in the shaping of public opinion and in the delivery of relief and development assistance worldwide.15 In 1986 NGOs spent over $3 billion for development-related activities,16 and UN operational agencies increasingly sought them out as implementing partners for their programs.

Church groups were among the first to feel the impact of the growing number of internally displaced persons. By the late 1980s those affiliated with the World Council of Churches (WCC) were finding their resources strained to the limit in providing food, shelter, and protection to southern Sudanese who had fled to camps on the outskirts of Khartoum to escape the ravages of the civil war in that country, and to similarly displaced populations in El Salvador and Sri Lanka.

The link between human rights and refugee and IDP issues was under discussion both at the WCC’s Geneva UN office and in Washington at the Refugee Policy Group, a think-tank set up in 1982 by Dennis Gallagher. A former Carter administration political appointee, Gallagher had big ideas for RPG and the entrepreneurial talent to make them happen. The board of trustees that he organized included prominent names in the refugee field: Alice Henkin, Doris Meissner, Robert Nathan, former Canadian secretary of state for foreign affairs Flora MacDonald, and Kitty Dukakis, wife of the 1998 Democratic Party’s presidential candidate; and later Francis M. Deng who had left Sudanese government service and in 1988 became a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and director of its Africa Program.

Gallagher and his deputy Susan Martin gathered a team of energetic professionals researching and writing on a broad range of refugee and migration issues. The main focus at first was on refugee resettlement in the United States and asylum and protection. Some initial work on refugee problems in developing countries suggested that there was little difference in the problems on b...