- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In order to understand drug metabolism at its most fundamental level, pharmaceutical scientists must be able to analyze drug compound structure and predict possible metabolic pathways in order to avoid the risk of adverse reactions that lead to the withdrawal of a drug from the market. This title is a comprehensive guide for recognizing the chemica

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Drug Metabolism by Jack P. Uetrecht,William Trager in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

The response of different patients to a drug varies widely and, depending on the drug category, from 20% to 75% of patients do not have a therapeutic response (1). In addition, many patients will have an adverse reaction to a drug. There are many reasons for these interindividual differences in drug response, both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic. In order to begin to understand these differences, it is essential to understand what happens to a drug in the body. Most drugs are given orally and some drugs have variable and incomplete absorption. The major determinant of absorption is the physical properties of the drug. Once in the body, most drugs are converted to multiple metabolites. This process can begin in the intestine or liver before the drug even enters the blood stream. Metabolism is often required in order for the body to eliminate a drug. However, some drugs are prodrugs, i.e., in order to exert a therapeutic effect they require metabolism to convert them to an active agent. Examples include enalapril, which has better oral bioavailability than the active agent, enalaprilate, and is readily activated by hydrolysis, and codeine, which must be metabolized to morphine in order to be an effective analgesic (Fig. 1.1).

The enzyme that converts codeine to morphine is polymorphic, and about 7% of the North American population lacks the cytochrome P450 (CYP2D6) needed to perform this conversion; now we understand why codeine does not work in these patients while others have an exaggerated response because of very high levels of CYP2D6 (2). There are several such metabolic enzymes that have common genetic polymorphisms caused by differences in a single nucleotide that influences enzyme expression or protein structure. Classically, this leads to a bi- or even trimodal distribution of enzyme activity in a population. In principle, this could be due to differences in intrinsic activity of the enzyme, but in most cases the genetic variant has very low levels of the enzyme, usually because of rapid protein degradation (3). Such polymorphisms can result in an interindividual difference of more than 100 fold in the blood levels of a drug that is metabolized by a polymorphic enzyme. Examples of polymorphic metabolic enzymes are listed in Table 1.1 (2,4,5). Other metabolic enzymes have more of a Gaussian distribution of enzyme activity in a population, i.e., they do not exhibit a classic bimodal distribution. This is because there are no common variants leading to large differences in enzyme activity and/or because the expression of the enzyme is strongly influenced by environmental factors. A good example of such an enzyme is CYP3A4 whose activity also varies greatly from one individual to another. In a recent study, it was found that the CYP3A4 activity of microsomes from different human livers varied by more than a factor of 100 and this correlated strongly with the level of CYP3A4 protein; however, no single factor was found to be responsible for this large variation (6).

FIGURE 1.1 Metabolic conversion of prodrugs to pharmacologically active agents.

Furthermore, some metabolic pathways, such as glucuronidation and amino acid conjugation, are deficient at birth thereby making newborns more sensitive to drugs that are cleared by the enzymes involved. In the case of glucuronidation and newborns, this is particularly important because glucuronidation is the primary mechanism for the elimination of bilirubin, the breakdown product of hemoglobin, and the increase in the levels of bilirubin leads to jaundice. Another aspect of drug variability that impinges upon therapeutics is that many drugs and other xenobiotics, i.e., chemicals that are foreign to the body, can increase or decrease the levels/activity of metabolic enzymes leading to drug–drug interactions.

TABLE 1.1 Examples of Common Polymorphic Metabolic Enzymes

Although many drugs require metabolism in order for them to be cleared from the body, many adverse effects of drugs are mediated by metabolites. In particular, it appears that most idiosyncratic drug reactions are caused by chemically reactive metabolites of drugs, and interindividual differences in metabolism of a drug may contribute to the idiosyncratic nature of these adverse reactions. However, the mechanisms of idiosyncratic reactions are not really understood, and even though there is evidence that reactive metabolites are involved, genetic polymorphisms in enzymes responsible for forming the reactive metabolite that appears to be responsible for a given idiosyncratic reaction do not appear to be the major factor leading to the idiosyncratic nature of these adverse reactions (7).

The goal of this book is to provide a basic understanding of how drugs are converted to metabolites and how these transformations can change the physical and pharmacological properties of the drug. In order to gain a basic understanding of drug metabolism, it is essential to have a basic understanding of chemistry. To make this material more accessible to nonchemists, in Chapter 2 we review the basic chemical principles required to fully appreciate the subsequent chapters. It is also important to be able to mathematically describe the rates of metabolism and other processes that control the concentration of a drug and therefore a review of pharmacokinetics is provided in Chapter 3. Drug metabolism is commonly divided into phase I (oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis) and phase II (conjugation); this implies that phase I metabolism occurs before phase II metabolism. However, if a drug can undergo phase II metabolism, phase I metabolism may make a minor contribution to the clearance of a drug and we have chosen to organize the pathways according to their chemical nature, i.e., oxidation, etc. As mentioned above, many adverse effects of drugs appear to be due to chemically reactive metabolites; therefore, the last chapter is a discussion of reactive metabolites.

Although the emphasis is on drugs, the same principles apply to any xenobiotic agent. The major difference between drugs and other xenobiotics such as environmental toxins is the dose. The dose of common drugs is usually on the order of 100 mg/day and can be more than a gram a day; in contrast, exposure to most other xenobiotics is typically much lower.

REFERENCES

1. Spear BB, Heath-Chiozzi M, Huff J. Clinical application of pharmacogenetics. Trends Mol Med 2001;7(5):201–204.

2. Wilkinson GR. Drug metabolism and variability among patients in drug response. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(21):2211–2221.

3. Weinshilboum R, Wang L. Pharmacogenetics: Inherited variation in amino acid sequence and altered protein quantity. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004; 75(4):253–258.

4. Evans WE, Johnson JA. Pharmacogenomics: The inherited basis for interindividual differences in drug response. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2001; 2:9–39.

5. Weinshilboum R, Wang L. Pharmacogenomics: Bench to bedside. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004; 3(9):739–748.

6. He P, Court MH, Greenblatt DJ, et al. Factors influencing midazolam hydroxylation activity in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos 2006; 34(7):1198–1207.

7. Uetrecht J. Idiosyncratic drug reactions: Current understanding. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2007; 47:513–539.

2

Background for Nonchemists

Although nonchemists are usually intimidated by chemical structures, drugs are chemicals and a basic understanding of chemistry is necessary to understand the properties of drugs. The name of a drug is arbitrary and provides little or no information about the drug, but the structure defines a drug and provides many clues as to the likely properties of the drug. It is a valuable skill to be able to look at the structure of a drug and be able to predict with a reasonable degree of certainty many of the properties of that drug; one of the goals of this book is to facilitate developing this skill and to make it more accessible to nonchemists. Although the focus of this book is on drugs, in principle, drugs are no different than other xenobiotics (any foreign compound, be it from an herbal product or a chemical waste).

USING THE STRUCTURE OF A DRUG TO PREDICT PROPERTIES SUCH AS WATER SOLUBILITY

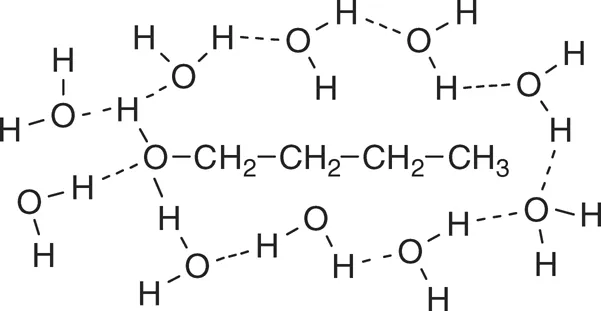

The properties and pharmacological effects of drugs are due to their interactions with other molecules such as enzymes and receptors. Water solubility, which is a very important property of a drug, is based on interactions with water. Ion–dipole interactions are the strongest and therefore drugs that are mostly charged at physiological pH usually have high water solubility. The next strongest interaction is hydrogen bonds. Therefore, drugs that contain O–H or N–H groups are, in general, more water soluble than those that do not have such groups. However, the presence of one O–H group on a large molecule is not sufficient to confer high water solubility. Solubility is based on the balance of bonds formed and broken. Strong interactions with water molecules obviously promote water solubility, but interactions between water molecules must be broken to form these new interactions. Even hydrophobic drugs interact with water, but the energy of the bonds between water molecules that must be broken in the process of dissolving the hydrophobic drug in water is much greater than that of the bonds between the drug and water; therefore, hydrophobic drugs have very low water solubility. As shown in Figure 2.1, 1-butanol is surrounded by water molecules. There are hydrogen bonds between the water molecules and between water molecules and the OH of butanol, but the interactions between the water molecules and the hydrocarbon part of butanol are weak and interactions between water molecules have to be broken in order to dissolve the butanol. 1-Butanol is soluble in water, but unlike ethanol, it is not miscible in all proportions in water and alcohols with a longer alkyl chain are less soluble.

FIGURE 2.1 1-Butanol surrounded by water molecules showing possible hydrogen bond interactions.

Likewise, another factor that affects water solubility is the strength of interactions between the drug molecules that must be broken when the drug dissolves. One clue to the strength of these interactions is the melting point of a drug. Other factors being equal, liquids are more water soluble than solids and, with the exception of salts, drugs with a high melting point usually have low water solubility. For example, in a comparison of sulfadiazine and sulfamethazine (Fig. 2.2), the only difference between the two molecules is the presence two methyl groups on sulfamethazine. Even though the methyl groups are “hydrophobic” and decrease the strength of the molecule’s interactio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Background for Nonchemists

- 3. Background for Chemists

- 4. Oxidation Pathways and the Enzymes That Mediate Them

- 5. Reductive Pathways

- 6. Hydrolytic Pathways

- 7. Conjugation Pathways

- 8. Reactive Metabolites

- Index