eBook - ePub

Cultural Studies

Volume 6, Issue 1

Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway, Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway

This is a test

Share book

- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultural Studies

Volume 6, Issue 1

Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway, Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Now under new editors, Cultural Studies explores popular culture in a uniquely exciting and innovative way. Encouraging experimentation, intervention and dialogue, Cultural Studies is both politically and theoretically rewarding.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Cultural Studies an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Cultural Studies by Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway, Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Cultura popolare nell'arte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ARTICLES

FROM GESTURE TO ACTIVITY: DISLOCATING THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCRIPTORIUM1

DAVID TOMAS

All writing is an index of law. (Pierre Clastres, 1987a:177)

The place of a tactic belongs to the other. (Michel de Certeau, 1988:xix)

Everything is related to the body’, observes Jean Starobinski (1989:353), ‘as if it had just been rediscovered after being long forgotten.’ With these words Starobinski draws attention to a recent eruption of literature devoted to the body’s multifarious histories and forms. It is a literature, moreover, that has proliferated to such an extent that one can now speak of a ‘fin-de-siècle’ platitude: the body is no longer ‘object’ (biological or otherwise) but a series of discursive traces. Although one would imagine that ethnography has provided an abundance of material for this evolutionary mutation from chromosome to text,2 one is surprised to note that the ethnographer has escaped a similar process of textualization, although the authority of one of the principal products of ethnographic activity—writing—has dissolved under the corrosive gaze of a critical textual politics. This paradox is amply illustrated in the case of the ‘timely’ publication (Spencer, 1989) of a collection of essays entitled Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. The collection of articles —boldly presented as ‘Experiments in contemporary anthropology’— is varied and contradictory in its approach to its subject, and yet its title and introductory essay speak eloquently of a new ethnographic moment—of writing about the writing of culture—which is clearly the product of an explosive mixture of poststructuralist thought, with its emphasis on a textually based interdisciplinary approach to the production of social knowledge, and an emergent self-reflexivity on the part of anthropologists. As such, the collection celebrates a late-modernist form of natural selection: a self-confessed, apologetic, yet determined predisposition toward shedding ‘a strong, partial light’ or ‘a defensible, productive focus’ (Clifford, 1986a:21, 20) on the experimental ethnographic applications of contemporary textual theory and practice, applications clearly (though not exclusively) proclaimed and defended in James Clifford’s introductory manifesto on ‘Partial truths’.

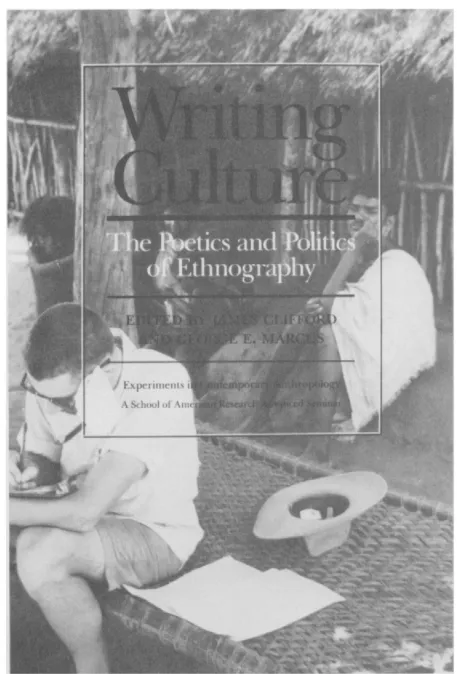

Clifford’s celebration of a new ‘emergent interdisciplinary phenomenon’ and his assertion that the ideology of the ‘transparency of representation and the immediacy of experience’ (Clifford, 1986a:3, 2) has crumbled in the face of an approach to ethnographic texts that proclaims the contested nature of culture and the ‘artisanal…worldly work of writing’ ethnography (1986a:6), highlights ethnography’s contemporary ‘historical predicament’ (1986a:2). Such proclamations have none the less been received with a certain amount of scepticism in a variety of quarters (see Rabinow, 1986:245; Gordon, 1988; Mascia-Lees, Sharpe, Cohen, 1989:13) which is understandable given the author’s focus on a male-dominated practice of writing to the exclusion of other gendered/indigenous forms of ‘ethnographic’ inscription. The complex and contradictory nature of this exclusionary focus is amply illustrated by a curious description, at the beginning of Clifford’s essay, of a photograph that not only adorns the cover to this self-proclaimed ‘controversial collection’ of ‘post-anthropological’, ‘post-literary’ essays (Clifford, 1986a:24, 5), but also acts as a frontispiece to the collection as a whole.3

Our Frontispiece shows Stephen Tyler, one of this volume’s contributors, at work in India in 1963. The ethnographer is absorbed in writing—taking dictation? fleshing out an interpretation? recording an important observation? dashing off a poem? Hunched over in the heat, he has draped a wet cloth over his glasses. His expression is obscured. An interlocutor looks over his shoulder—with boredom? patience? amusement? In this image the ethnographer hovers at the edge of the frame—faceless, almost extraterrestrial, a hand that writes. (Clifford, 1986a:1)

We are witness in this passage to the contradictory birth of a particular ‘textualist meta-anthropology’ (Rabinow, 1986:243), for Clifford’s claim that this image is ‘not the usual portrait of anthropological fieldwork’ serves as an originary moment for another history—the history, in his words, of ‘a hand that writes’.

In the following pages, I want to question the political validity of the enterprise launched through this descriptive passage by challenging the notion that ethnography ‘is always writing’ (Clifford, 1986a:26), for I believe that one cannot construct critical or oppositional practices on the basis of privileging ‘literary processes’ to the apparent exclusion of all other modes of representational production and reproduction that ‘affect the ways cultural phenomena are registered’ (1986a:4). To focus exclusively on writing is to marginalize other ‘social technologies’ (see de Lauretis, 1987:2), and in particular other contemporary technologies of observation/ inscription that determine and fix the parameters of ethnographic vision, by truncating ethnographic practice into an activity that begins with ‘the first jotted “observations’” and ends with the ‘completed book’ whose literary ‘configurations “make sense” in determined acts of reading’ (Clifford, 1986a: 4). This process of marginalization is, moreover, clearly at odds with a textual practice predicated, as we have seen, on a visually inspired originary moment. I will argue that the exclusive focus on a writerly system4 for the representation or invention of culture(s) (Clifford, 1986a:2) has important consequences for the development of effective critical strategies and local tactics devoted to the production of alternative forms for postethnographic, postcolonial stories. I argue, further, that this type of literary myopia can only be redressed in the course of a critical reassessment of the observational preconditions of modernist and postmodern ethnographic activity,5 and that this can only be finally achieved by embracing an intersystem of hybrid technologies and creolized activities that include but are not dominated by the types of ethnographic figures of authority and writerly practices proposed by the current generation of postanthropological writerly theorists (see Marcus and Cushman, 1982; Marcus and Fischer 1986; Clifford, 1986b). It is only by situating such an intersystemic approach in relation to (that is between) dominant disciplinary practices that one can engender an alternative identity for an observer and pattern of observation (from the Latin ob over, against, and servare to keep safe, preserve, conserve: observare—to watch over (physically and morally), to respect, to heed appropriately (Partridge, 1983:446)) or pattern of looking to call into question anthropology’s natural historically sanctioned methodological propensity to mask its often violent origins.

However, it must be emphasized that the choice of vision as a principal site for generating critical or oppositional postanthropological activities is both strategic, based as it is on its dominant role in constructing anthropological knowledge of other peoples (see Fabian, 1983; Tomas, 1987) and a recent resurgence of interest in alternative ethnographic practices rooted in early twentieth-century avant-garde art (Clifford, 1988d; Marcus, 1990). It is also contingent on my ongoing personal interest and engagement in oppositional anthropo-visual activities in contemporary visual art (see Tomas, 1984). James Clifford has produced a seminal body of essays (see Clifford, 1986a, b;1988a) that has gained a wide audience, influence and currency because of its modernist critiques of anthropological authority, the most radical of which have been concerned with the interpenetrations between French anthropologists and surrealists in the inter-war years in Paris and the potential consequences of this cross-fertilization for a contemporary surrealistic ethnography. Although Clifford seems to have retreated, in recent works, from the radical aesthetico-epistemological thrust of his earlier historical and critical ruminations on a surrealistic ethnography, this work still stands at the limits of the current crisis in (Western) representation as articulated in advanced anthropological debate and is thus worthy of detailed consideration. It is especially worthy of critical attention since a surrealistic ethnography engages two of the principal contested domains of a Western humanist imagination: Art and Ethnography.

The academic production of ‘unproductive’ bodies

For writing can tell the truth about language, but not the truth about reality (we are at present trying to learn what a reality without language might be). (Roland Barthes, 1971b:320)

Photography displaces, shifts the notion of art, and that is why it takes part in a certain progress in the world. (Roland Barthes, 1980a:360)

The appearance of a disembodied hand at the end of a process of defamiliarization in which the ethnographer is refashioned into an extraterrestrial is a powerful, pivotal image. It not only glosses the intertextuality of the ethnographer’s body but it also highlights the exclusionary practices that marginalize less useful bodies—bodies, in other words, that have no apparent disciplinary role in the production of ethnographic and metaethnographic Knowledge. However, such gratuitous figurative violence does not remain unchallenged for bodies are not necessarily written, invented or fragmented according to such academic stories. In fact, ‘Tyler’s’ photograph provides evidence of a more complicated deployment of the body across and between different technologies of observation/inscription (the pen and camera) and inscriptive sites (the page and photograph)— evidence that suggests that the privileging of one or other of these technologies/sites not only does violence to the body itself but also obscures a prime contestatory function of one of these systems, for the body can also be seen. Indeed, the photograph betrays the existence of other figures—a woman and two children—in addition to the two who figure in Clifford’s originary tale. Why, one wonders, are these figures not acknowledged in this originary tale? Are such exclusions to be considered as further examples of Clifford’s gendered postanthropological agenda, a bias that has already attracted commentary from feminist anthropologists (see Gordon, 1988; Mascia-Lees, Sharpe, Cohen, 1989: 13–14) and cultural critics (Grossberg, 1988:389n. 7)? This possibility is certainly endorsed by a further significant omission: Martha G.Tyler is acknowledged to have taken the Tyler photograph—an important observation that does not draw further commentary as to its potential as source for other gendered roles and media histories implicated in the production of ethnographic knowledge. Moreover, the question of ethnography and its exclusive media histories is again highlighted by a cursory reference to two other photographs of prominent anthropological authorities—Margaret Mead (one of the few women who have attained mythic stature in this predominantly male-dominated discipline and who as a consequence can be ‘naturally’ accorded a named position) and Bronislaw Malinowski—that serve as additional cornerstones in Clifford’s postliterary manifesto on ‘the making of texts’ (Clifford, 1986a:1–2)). Given the fact that visual representations are of considerable importance in articulating an agenda to reconstitute ethnographic practice, given writing’s constitutive originary role in this story one can only assume that Clifford speaks with the traditional authority of the academic scribe, that is from the position of someone who seeks to designate and control a privileged channel of textual production and ethnographic ‘invention’.

Cover, Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Photograph of Stephen Tyler in the field. Photograph by Martha G.Tyler.

The deftness of hand that has allowed Clifford to begin ‘not with participant-observation or with cultural texts (suitable for interpretation), but with writing, the making of texts’ (1986a:2) has succeeded in establishing its sovereign claims in regard to writing and inventing culture(s) by way of an interpretive gesture that renders the figure of the other as an abstract nameless ‘interlocutor’. Or it has consigned it outside of the rebellious and innovative domain of writing (as in the case of the woman and child)—a condition that is unfortunately exacerbated by the graphic layout of the book’s cover where the underlined portion of the title is positioned (almost as if to emphasize the gestural powers of the hand that writes) so as to effectively occlude the eyes of the woman in the background (Gordon, 1988:8). It should therefore come as no surprise, given such an inscriptive emphasis on

Same:Other:: Ethnographer:Native:: Named:Unnamed:: Writing:Photography,

that one occasionally discovers anonymous bodies inscribed in photo-chemical emulsions, testimonies to ordinary lives that have no place in the politics of disciplinary interpretation and the ‘micropractices of the academy’ (Rabinow, 1986:253). These bodies are the neutral or anonymous grounds upon which the metadescription of the ethnographer is situated. This point is of considerable importance, for although Clifford reminds us (1986a:3) that ethnography’s ‘authority and rhetoric have spread to many fields where “culture” is a newly problematic object of description and critique’ he fails to note that it is, in fact, its observational practices—its use of techniques of participant-observation—that have allowed for the regeneration of critical approaches in other fields (see Radway, 1988:367; Grossberg, 1988). Thus, it is in terms of the capillary action of its observational practices that ethnography is being transported along the fissures and faults of ‘culture’. Notwithstanding this important fact, ethnography’s contested domain is not, as one might expect, its observational practices—its modes of looking—but as Rabinow points out (1986:241–7) the Academy and its principal site of inscription: the book.

The figure of the writer is an important motif in recent critical theory, which is not surprising since most of the protagonists who have been engaged in promoting its iconoclastic practices have been concerned with the art of writing. Thus a writer’s presence at the beginning of Clifford’s introductory text signals not only the author’s current gene...