![]()

Section One:

Conceptualizing and Studying Cultural Participation

![]()

1 Engaging Art

What Counts?

Steven J. Tepper and Yang Gao

Introduction

Recently, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) released a report titled Reading at Risk based on a government-sponsored 2002 survey of arts participation. The report, discussed in the mainstream news and by countless pundits and Internet bloggers, found that fewer Americans today are reading poetry and literary fiction compared to a decade ago, and alarmingly, the most dramatic declines were among young people.

Readers at Risk takes its place in a long line of similar reports and news articles that document the health and vitality of the arts in the United States by measuring trends in participation for the benchmark art forms: ballet, classical music, opera, theater, museums, literary fiction, and jazz. Big arts associations, like the American Association of Museums and the American Symphony Orchestra League, have commissioned studies based on ticket sales, admissions, and attendance figures. The federal government tracks arts participation every five years (since 1982) through the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA). The polling firm Louis Harris and Associates has sponsored five public polls in their Americans and the Arts series. There are dozens of other national and local participation studies.1 The findings from these studies vary extensively as the result of differences in the wording of survey questions, the types of arts activities explored, the composition of the population surveyed, and, of course, the year of the survey (Tepper 1998). But regardless of the findings, which range from optimism to pronouncements of demise, there has been a persistent interest in the size and scope of arts participation for well more than three decades.

This chapter argues that the enduring interest in arts participation has shifted from a broad concern with democratic life to a more narrow concern with attendance at nonprofit arts institutions. These findings link cultural participation with other forms of social engagement (i.e., political and religious), drawing attention to a shared social context and trajectory. Given the similarities, we believe arts participation should be analyzed within a more coherent framework that considers multiple forms of social involvement. Furthermore, by focusing its attention almost exclusively on attendance, the arts community has largely ignored important forms of artistic practice. Interestingly, when artistic practice (i.e., making and performing the arts) is compared with more traditional measures of attendance, it is found that barriers of age, income, and education become less significant. This tentative finding implies that citizen engagement in the arts might be healthier than some would think; it also suggests that a broader view of participation can help reconnect the arts with concerns for social equality, individual expression, and participatory democracy. Before examining new analysis, the chapter traces the history of America’s preoccupation with the idea of participation.2

Participation in Context

Alexis de Tocqueville, the French historian and political thinker who visited the United States in the early 1830s, produced one of the most enduring and trenchant analyses of American habits, customs, and beliefs: Democracy in America. For Tocqueville, the vigorous egalitarianism and democracy that defined the new republic emanated from, and in turn cultivated, a participatory spirit. He wrote, “No sooner do you set foot upon American ground than you are stunned by a kind of tumult. Everything is in motion around you” (Tocqueville 2004, p. 249). Galvanized by a propensity to participate, Americans started churches and attended religious services regularly; they joined in quilting circles and community sings, formed associations, and participated in local politics. This active engagement in a range of political, social, religious, and cultural affairs, Tocqueville argued, protected citizens from drifting toward tyranny and despotism.

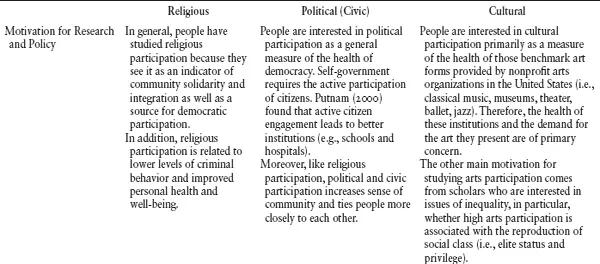

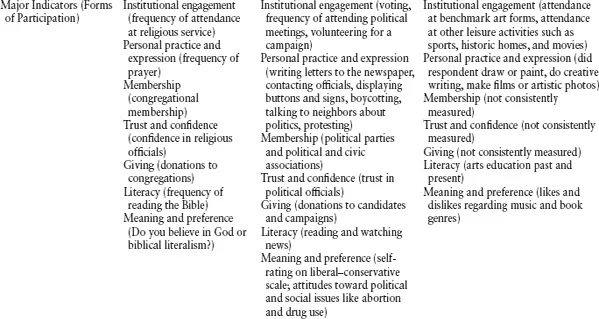

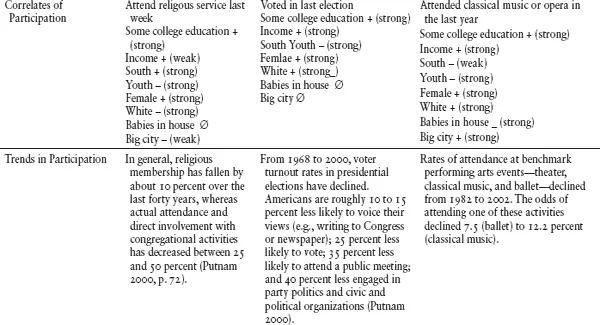

Tocqueville was not alone in pointing out the association between participation and a healthy and spirited society, and over the years three forms of participation have attracted the interest of American intellectual and political leaders: political and civic participation, religious participation, and cultural participation. Given the historical connection among all three forms, the attempt is made to compare them systematically. In particular, the chapter looks at (1) the motivations for studying participation; (2) the major indicators of participation employed in the scholarly literature; (3) the correlates of participation; and (4) trends in participation. All of these dimensions are summarized in Table 1.1.

Motivations for Studying and Tracking Participation

In general, scholars have approached religious and political participation out of a concern for collective outcomes (i.e., democracy and community solidarity) and individual well-being (i.e., health and well-being). As mentioned earlier, writers have long argued that democracy requires active citizens who pursue and protect both their own interests and the interests of their communities. Obviously, political participation is the most direct form of self-government, and voter turnout rates, which serve as a measure of political participation, have long been seen as a proxy for the health of democracy. More recently, as discussed following, Robert Putnam (2000) and others have looked beyond voting to a range of other forms of civic participation, from attending political meetings to joining civic clubs.

Table 1.1 Comparing Religious, Political, and Cultural Participation: Indicators, Correlates, Motivations, and Trends

As for religious participation, reformers and advocates have monitored church attendance, the growth of denominations, and the presence of religious pluralism. These measures of participation have historically been linked to democratic life as religious congregations have been important conduits for mobilizing voters and providing their congregants with skills required for political activity. Thus, democracy prospers when there are more religious institutions, representing more denominations, and serving more Americans (Putnam 2000, pp. 65–66).

In addition to concerns about self-government—and consequent fears of big government and big business—scholars have long worried about the effects of modernization on social solidarity and community. In particular, they feared that the industrial economy would lead to a breakdown of the social fabric, individual alienation, and, ultimately, a decline in people’s willingness to trust each other. In this regard, declines in both religious and political participation are seen as signs of a larger social collapse.

Like religion and politics, initial concern about cultural participation also centered around the health of U.S. democracy. Tocqueville, again, believed that democracy and cultural participation were mutually reinforcing. He wrote that in America, “the taste for intellectual enjoyment will descend, step by step, even to those who, in aristocratic societies, seem to have neither time nor ability to indulge in them” (DiMaggio and Useem 1977, p. 8). Similarly, early advocates for American museums promoted widespread participation in an attempt to elevate taste and, consequently, to bring about a more enlightened citizenry. Thus, as early as the late nineteenth century, museums began to track attendance figures, in part to justify their reach and influence. Building participation in the arts also animated the work of musical progressives from the 1870s through the 1930s. These progressives, beginning with the founders of the Hull House Music School in Chicago, believed that enlarging the audience for music—through public concerts, festivals, community sings, and free music lessons—was an essential democratizing force in America (Vaillant 2003). Of course, underlying the interest in arts participation is the idea that egalitarianism, the hallmark of American democracy, requires not only equal access to material and political resources (i.e., “the opportunity to do well for yourself”) but also to culture (i.e., “the opportunity to live well”).

In fact, DiMaggio and Useem (1977) traced the idea for a national survey of arts participation—what became the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts or SPPA—to a concern about democracy and equitable access. Writing about national arts policy in the 1970s, they noted, “The vast increase in the level of public support for the arts has stimulated concern about the social composition of the expanding arts public. Policy makers and interest groups increasingly ask if government programs are underwriting an activity enjoyed by a large cross section of the American public; or are they backing an activity that remains the special preserve of an exclusive social elite?” (p. 180). The implication here is that the government has an interest in democratizing the arts by expanding access.

Along with an interest in participation for democracy’s sake, arts leaders were interested in measuring participation for the benefit of arts institutions. Beginning in the late 1960s, America witnessed a dramatic rise in the number of arts organizations, fueled in part by grants from the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, as well as from the newly formed National Endowment for the Arts. These organizations often conducted audience surveys as a means of gauging demand, justifying requests for public support, and thinking strategically about marketing and future growth. But many of these audience surveys were poor in quality and dissimilar enough that making comparisons across organizations or compiling a national portrait of participation was virtually impossible. So, the NEA launched a national survey, the SPPA, which could help track trends in participation, thus providing arts organizations with important data for advocacy and strategic planning.

The emphasis on the health of arts organizations influenced the nature and design of the survey, as well as the indicators that track cultural participation in the United States. Most of the questions on the SPPA focus on live attendance at benchmark cultural forms that are provided mainly through nonprofit arts organizations and venues: theatre, classical music, opera, ballet and modern dance, and museums. Of course, these organizations, as well as the artists they represent, were and are the primary stakeholders for the agency, which had organized its grant making to support their activities. So, tracking attendance at these benchmark forms was one way the NEA could provide useful information to its primary clients while at the same time tracking whether these benchmark forms were reaching a broad section of the American public and thus were serving democratic goals.

Although the National Endowment for the Arts saw its efforts to collect national participation data as meeting both goals—serving existing institutions and the public interest—the goals were not entirely compatible. Richard Orend (1977) wrote one of the early monographs that influenced the creation of the SPPA. In it, he discussed the tension that exists from trying to meet these two goals and argued that one or the other will have to drive the design of any future national survey, but not both. Ultimately, he noted that the NEA would have to decide if its role was to promote a broader range of activities, giving people what they want, or to enhance those already determined to be within its scope, preserving traditional high culture institutions. The NEA emphasized the latter goal, which makes perfect sense given that its programs were already organized around existing traditional high culture institutions. Of course, NEA programs have evolved to include a more eclectic set of arts activities, including folk arts and film, and its national survey includes some broader questions about other leisure activities and about amateur art making. But on the whole, the survey emphasizes attendance at the benchmark art forms.

In sum, it is fair to say that studies of political and religious participation are more concerned with what may properly be considered the public interest—the health and functioning of society and its citizens. Like the arts, scholars in these two areas have also been interested in the shape of institutions, such as the strength of political parties or the rise and fall of particular denominations. These concerns, however, are overshadowed by the larger question of whether citizens are becoming more or less engaged, trusting, and connected to one another. On the other hand, concern for arts participation, though once part and parcel of a historical preoccupation with the health of a participatory democracy more broadly, has become less connected to the public interest arguments and has been focused on the health of nonprofit cultural institutions, especially in the last few decades. Although there is preliminary research on the relationships between arts participation and (1) general social engagement (Stern and Seifert 1998) and (2) individual well-being (e.g., health, happiness, educational success), these studies have remained relatively local and have not been a major force motivating national studies of participation.3

Indicators of Participation

Participation can mean many different things. When existing studies are examined across the three domains—religion, politics, and culture—it is revealed that modes of participating fall roughly into six different areas, with some overlap between them. First, participation can involve engagement with an institution; in other words, participation is geared toward supporting or interacting with some formal organization, structure, or institution, typically in a manner that is relatively predetermined (i.e., there is a time, place, and agreed-on method of engaging). Institutional participation can involve attending events, volunteering, voting, and going to church.

A second mode of participation involves personal practice and expression, which emphasizes activities that require some personal competency and commitment and which often involve some form of individual expression. These activities can be more private and selfdetermined than institutional engagement (e.g., playing the guitar in one’s bedroom, praying to God), or they can be collective (e.g., playing in a band, taking part in a protest event). Although there is clear overlap with institutional engagement, this form of engagement is less bound by the needs, interests, and routines of organizations and, ultimat...