eBook - ePub

Gender-Class Equality in Political Economies

Lynn Prince Cooke

This is a test

Share book

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gender-Class Equality in Political Economies

Lynn Prince Cooke

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Gender-Class Equality in Political Economies offers an in-depth analysis of gender-class equality across six countries to reveal why gender-class equality in paid and unpaid work remains elusive, and what more policy might do to achieve better social and economic outcomes. Thisbook is the first to meld cross-time with cross-country comparisons, link macro structures to micro behavior, and connect class with gender dynamics to yield fresh insights into where we are on the road to gender equality, why it varies across industrialized countries, and the barriers to further progress.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Gender-Class Equality in Political Economies an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Gender-Class Equality in Political Economies by Lynn Prince Cooke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Diritto & Diritto di genere. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Gender-Class Equality Over Time

Introduction

Equality in industrial economies remains elusive. Gender, class, and ethnic gaps in education, employment, and domestic tasks all persist in the twenty-first century, despite the equal opportunity, affirmative action, and gender mainstreaming policies enacted during the twentieth century. Today, women often complete more years of education than men, but afterwards gender inequalities in paid and unpaid work widen across adulthood. More men than women are employed continuously and work full- rather than part-time. Men also enjoy greater average wages. Women, in turn, spend more time than men in unpaid housework and child care whether or not they are employed. So where did we stall on the road to gender equality in paid and unpaid work?

This book answers this question by tracing how state policies structured relative gender and class equality in Australia, East and West Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The state was a new entity that evolved with industrialization (Anderson 1974; Weber 1968). Yet classical liberal tenets held that any state interference in the market would undermine economic efficiency and growth (Freeden 1978). The “invisible hand” of self-interest (Smith 1970 [1776]: 184) ensured market efficiency as individuals negotiated work hours and wages directly with employers. The resulting income inequality created the necessary individual incentive for further economic growth (Kuznets 1963). States were therefore reluctant to implement any regulations or policies that affected the employeeemployer relationship.

States had their own interests, however, and were not simply handmaidens to the market. Concern over economic and military competitiveness and political stability encouraged governments to diverge from liberal tenets and introduce the first policies affecting individuals and the labor market (Freeden 1978; Glass 1967). Class-related policies regulated the training, work hours, relative wages, and benefits of those in employment. For example, England’s 1833 Factory Act restricted children’s employment hours and required employers to educate them (David 1980). Compulsory schooling expanded in all of the countries during this period, most rapidly in the United States. Germany introduced industrial accident insurance in 1871 and pensions in 1889 (Pierson 1998: Table 4.1). Australian men were guaranteed “family wages” with the 1907 Harvester Judgement.

The paid work of industrial production systems represented just half of modern life. Supporting it were the reproduction system and unpaid work associated with family. There are many forms of family, but state policies generally legitimated heterosexual families and different activities for the men and women within them (Collins 2000; Fink 2001; Walby 2009). Men were assumed to be the independent workers, although states frequently imposed further restrictions on immigrant men. Women were assumed to be responsible for the unpaid work that sustained families and communities (Pateman 1988). Women’s responsibility for society’s unpaid work limited their ability to be men’s economic equal in the market, and men’s responsibility for paid work limited their ability to provide equal unpaid support to families and communities.

All states therefore inserted gender, class, and other group differences in the work associated with the market and family. Yet states were not independent institutions. As detailed in this book, the specific policies implemented and the resultant group differences reflected other institutions. For example, the institutions of “family” and “market” differed across countries. In Spain and West Germany, Roman Catholic precepts strongly influenced family policy. The church was also an important provider of education and charity in Australia and England. Ethnic divides differed as well. Densely populated European countries sent migrants; the Americas and Australia received them.

The state was therefore a single institutional pole in what I call an institutional equality frame that structured relative gender, class, and other group equality in paid and unpaid work. The frame was not a simple border around the market and family, but an institutional cage that constrained group choices among the components of paid and unpaid work. Components of paid work included employment hours, occupations, wages, autonomy, supervision, and the like. Unpaid work components included child and elder care, cooking, shopping, housework, running errands, and community volunteer work. These components of work complemented each other within the institutional frame, but not all work components were equally valued. As noted by Heidi Hartmann (1981: 18): “Capitalist development creates places for a hierarchy of workers, but … [g]ender and racial hierarchies determine who fills the empty places.”

The institutional equality frame reinforced these hierarchies as state policies allocated the work of the new industrial order among social groups. Population policies affected who had children and who was responsible for their care, which reaffirmed the state’s desired class and ethnic mix as well as gender differences in unpaid work. Public schooling provided the bedrock of education and skills later rewarded in the labor market (Mincer 1974), but the schooling systems systematically privileged some groups over others. The regulation of work hours, wages, and entitlements to sickness, unemployment, and parental benefits reflected societal expectations of adults’ time allocations among employment, family, and leisure activities. These time allocations, in turn, created group differences in the accumulated work experience and on-the-job training that determined wages. Accumulated lifetime earnings determined individual financial circumstances in later years. State policies therefore affected relative group advantage and disadvantage from birth through old age.

Not all groups were subject to the same policies, but the group policies needed to complement one another just as the different components of “work” complemented one another (Verloo 2006). For example, policies that encouraged women to leave employment when they married created labor shortages. These shortages could be balanced by more open immigration policies. Immigration policies frequently controlled the numbers of ethnically diverse migrants, barred immigrants from bringing other family members, or restricted immigrants’ access to state provisions such as education and unemployment benefits (Sainsbury 2006). Our relative advantage or disadvantage within the institutional frame therefore cannot be determined by single characteristic such as gender or class or ethnicity, but by the accumulated policy effects at what Crenshaw (1989) termed the “intersection” of our group memberships (see also Hancock 2007; McCall 2001; Verloo 2006).

Each country’s frame therefore supported a given socio-economic equilibrium among the work components and social groups, but not equality for all groups. Any changes in the market, population, or policy in turn necessitated a reshuffling within the institutional equality frame to reach a new equilibrium. For example, class victories in early welfare state provisions advanced economic equality among more men, but often by limiting the employment opportunities for women, ethnic minorities, and immigrants (Freeman and Birrell 2001; Mink 1986; O’Connor 1993). Equal opportunity and affirmative action legislation implemented after World War II enabled some women and ethnic minorities to complete higher levels of education and pursue better jobs, but widened class differences within these groups (McLanahan 2004; Sobotka 2008). Growth in female employment increased class differences in unpaid work. Less-educated women and immigrant workers performed the domestic work of affluent households but could not afford to purchase such services for themselves (Anderson 2000; Gupta 2007).

In short, I argue the march toward greater equality stalled because its pursuit is a zero-sum exchange: advances for one group are invariably offset by losses for other groups or elsewhere within the frame. This offset could occur in a multitude of places. As will be shown here, policy support for greater class equality could lead to women’s exclusion from the labor market, women’s over-representation in part-time employment, and/or more unpaid work in the home. Policy support for gender employment equality crowded out time for unpaid work, which remained gendered. As a result, those who enjoyed the greatest degree of equality in paid or unpaid work sacrificed time and/or money. In other words, there is no policy or market “silver bullet” that eradicates gender-class inequality.

The State and Institutional Equality Frames

The zero-sum nature of gender-class equality over time has eluded us to date because it is not revealed in research focused on policy effects at specific historical periods,1 or that compared current gender equality in just one or two components of paid and unpaid work.2 In this book I combine comparative-historical and individual-level analyses to develop a more comprehensive picture of gender-class equality in national context and over time. The emphasis throughout the book will be the policy and market effects on relative equality in paid and unpaid work at the intersection of class and gender—hence “gender-class.” The comparative method is used to explore the comprehensive structures and large-scale processes that patterned social life (Tilly 1984). The outcome of interest is why gender-class inequalities in paid and unpaid work persisted across industrialized societies despite some impressive policy triumphs over the past half century.

Answering this question entails comparing how states institutionalized a group hierarchy through initial policies, regulations, and provisions, and the impact of subsequent policy innovations on gender-class equality. Institutions represent strategic contexts and shared cultural understandings (Grief 1994). These understandings affect the way economic, social, or political challenges are perceived and the range of possible solutions considered acceptable (Thelen 1999: 371). Most importantly, institutions reveal and reproduce power relations within a society (Stinchcombe 1997).

This book examines these processes by revealing (1) the different institutional arrangements that emerged in countries facing similar external pressures, (2) the role of institutions as coordinating mechanisms that sustained a country’s socio-economic equilibrium, and (3) what happened in the aftermath of significant social or policy change—i.e. what were the new gender-class equilibria (Levi 1997; North 1990; Pierson 2000; Thelen 1999).

To accomplish this, I trace the evolution of state provisions in Australia, Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States from the early nineteenth through the twentieth centuries. States all faced similar challenges in the process of industrialization: the best way to deal with worker mobilization (class), the new global flows of immigrants (ethnicity), and the sharp decline in fertility that accompanied industrialization (gender). As detailed here, countries differed in the level of concern generated by these changes. In the end, however, all states moved away from liberal tenets and instead took a more active role in ensuring individuals’ well-being or “welfare.”

States differed, however, in the nature of the new regulations and welfare provisions (Titmuss 1958). The historical comparisons reveal the diversity in policies and the institutions they complemented or created in each of the countries. The institutional equality frames also differed because of practical considerations. For example, Orloff and Skocpol (1984) argued that in the nineteenth century, the United States lacked the established civil bureaucracy of England that supported the latter’s early expansion of state welfare programs. Part of the difference stemmed from the US westward expansion during this period. Yet this same local expansion that thwarted development of national welfare programs fueled development of the locally based US public schooling system far ahead of Europe (Goldin and Katz 2008). In Australia and Spain, the state met the challenge of providing education to rural communities by supporting existing religious schooling. In Australia, this resulted in a class-stratified secondary educational system that contrasted with the labor market policies that ensured greater class equality. Geographic variation in state services formed another policy dimension that affected group differences within a country.

The resulting institutional equality frames legitimated specific discursive and material relations among social groups vis-à-vis “family” and the “market” in each country (Collins 2000; Walby 2009). A detailed discussion of the political debates from which the national policies emerged is beyond the scope of this book. Instead I focus on how the specific policy choices structured each country’s unique institutional frame of relative gender, class, and at times ethnic equality in paid work hours, wages, and unpaid work.

The Country Cases: Policy Effects on Class v. Gender Equality

The countries selected for comparison represent two sets of broadly similar countries in some aspects of policy, but they diverge in other policies that affect the gender-class intersections. Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States share a British political heritage, and the first state provisions generally adhered more closely to liberal tenets (O’Connor et al. 1999). In such “liberal welfare regimes” (Esping-Andersen 1990), individuals were expected to ensure their well-being via employment. England, for example, had a long legacy of differentiating between the deserving and undeserving poor (Orloff 1993a). The United States adhered to liberal tenets in the development of corporate rather than state welfare (Kalleberg et al. 2000; Skocpol 1992). Most people in the United States were made to rely on employer-provided sickness, disability, health insurance, and other benefits, whereas the Australian and British states offered more state protections. Australia differed further from the other two English-speaking countries because of its shortage of free (as opposed to prison) labor during the nineteenth century. This restricted labor supply enhanced working-class mobilization efforts, leading to the 1907 passage of the Harvester Judgement that guaranteed Australian men a family wage sufficient for supporting a wife and three dependent children (F. Castles 1985).

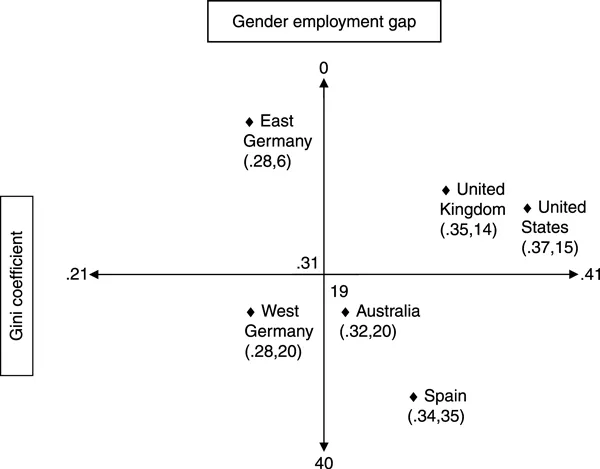

With less state interference in market mechanisms, liberal markets fostered greater income inequality (Kenworthy 2008). The Gini coefficient is a commonly used measure of income inequality. It ranges from zero to one, with larger numbers indicating greater inequality. As noted in Figure 1.1, the average Gini coefficient for OECD countries in 2000 was 0.31.3 The Gini coefficient for Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States exceeded that, indicating greater than average income inequality in these countries. At the same time, the degree of inequality across these three liberal regimes differed. As would be expected with their respective policy legacies, Australia’s income inequality was closer to the average, whereas the US market imposed the greatest inequality.

Source: The employment gap for 2000 is from the OECD Employment Outlook 2002, table 2.2 for men and women between the ages of 25 and 54. The Gini coefficient at the origin is also from OECD data, whereas the country Gini coefficients are from the Luxembourg Income Study Key Figures, www.lisproject.org/php/kf/kf.php, accessed February 25, 2010.

Figure 1.1 Relative gender-class equality in Australia, East and West Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States

Countries on the European continent implemented policies that sustained more social hierarchies than the liberal regimes. Corporatist elements required greater coordination among institutions such as employers, labor organizations, and the state (Esping-Andersen 1990; Hall and Soskice 2001). More of the population enjoyed some state welfare benefits as compared with the liberal regimes, but certain groups such as the elderly, civil servants, and skilled workers enjoyed superior benefits (Esping-Andersen 1990; Ferrera 1996).

The greater market coordination yielded greater income equality than in the liberal markets (Kenworthy 2008). This is most evident in the East and West German Gini coefficients displayed in Figure 1.1. Spain modernized much later than Germany and emerged from fascism during a period of intense global market competition (Noguera et al. 2005; Royo 2007). As a result, income inequality in Spain in 2000 was more similar to that of the United Kingdom than Germany.

The degree of class equality has been central to many mainstream welfare state theories (F. Castles 1985; Esping-Andersen 1990; Korpi 1983; Stephens 1979).4 Feminists, however, were quick to point out that class victories were rarely socially costless (Orloff 1993b). Under the laws of supply and demand that undergird free markets, improving the working conditions or wages of some workers required limiting the employment of others. Many class victories therefore created outsider groups, usually women, ethnic minorities, and/or immigrants. The greater the early class victories, the more likely women and immigrants encountered barriers to employment (Bertola et al. 2007).

Regardless of class equality provisions, all industrialized countries imposed labor restrictions on children’s and women’s employment before doing so for men (Wikander et al. 1995). These policies strengthened men’s position in paid work at the expense of women’s. Other policies relegated women to the private sphere to maintain families and communities (Gilligan 1996; Pateman 1988; Tronto 1993). Emphasizing women’s domestic duties addressed states’ concerns over declining fertility and coincided with the introduction of abortion and contraception regulation (Glass 1967). Many White middle-class women’s groups claimed all of society’s unpaid care work as a female prerogative (Bock and Thane 1991). Women’s care responsibilities also became embedded in new welfare institutions such as educational systems and health services. States supported these trends because women’s unpaid or low-paid care work reduced the public cost of providing welfare (Koven and ...