![]() I

I ![]()

1

A Global and Historical Introduction to Social Class

CIRECIE WEST-OLATUNJI AND DONNA M. GIBSON

A global understanding of social class in the literature specific to certain forms of helping through counseling has yet to be reached. This is due to several issues. The first is that counseling as a professional concept has yet to be embraced uniformly in an international context. While the counseling profession has some standing in the United States and Europe, more traditional mental health professions, such as psychology, psychiatry, and social work, are more evident in other regions of the globe (Portal, Suck, & Hinkle, 2010). Due to this reason, integrating social class issues into counseling has not been a priority for countries with emergent counseling programs. Rather, these programs typically focus on establishing themselves as legitimate degree programs with viable job placement opportunities for their graduates. A second issue that explains why a globalized conceptualization of social class has not surfaced is related to the complexity of the concept (Hutchison, 2011). In a meta-analysis of the concept of social class in mental health literature, Lin, Ao, and Song (2009) found that there were 89 different terms being used for this construct. This lack of a streamlined view of social class may, in part, be due to the fact that the term class is culturally situated and therefore relative. Finally, social class issues are enshrouded with socialized beliefs about self and other, thus making it difficult to separate our attitudes about social class from our ability to objectively define and employ our understanding in meaningful ways in our clinical practices (Balmforth, 2009; L. Smith, 2010).

With that being said, a useful definition of social class can be borrowed from the work of Kraus, Cote, and Keltner (2010), who suggested that, as a construct, “social class arises from the social and monetary resources that an individual possesses. Thus, social class is measured by indicators of material wealth, including a person’s educational attainment, income, or occupational prestige” (p. 1716). Why is an understanding of social class so important? Primarily, social class often defines one’s positioning in society—to what degree an individual receives privileges or is marginalized. In Western societies, such as the Americas and Europe, there is a perception that Western countries have moved to classless societies. However, social marginalization in health care, education, the workforce, and housing are evident. For instance, disproportionality in mental health diagnoses persists among lower-class individuals in the United States (Liu, Soleck, Hopps, Dunston, & Pickett, 2004). In other words, if you are poor, you are more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health condition than if you were middle class or above. This disproportionality in diagnoses, for example, has been linked to counselor misperceptions about individuals from lower classes (L. Smith, 2010). Yet, very little has been written about this phenomenon. What has been written has been conceptual or theoretical in nature rather than empirical.

SOCIAL CLASS AS A CONSTRUCT

Three areas shape the discussion of social class within mental health literature: (1) conceptualization of clients, (2) self-perception as clinician, and (3) intersectionality of identity for both clients and clinicians. Accurate conceptualization of client issues and needs is the hallmark of effective counseling (West-Olatunji, 2008). Clinician encapsulation has been discussed as a barrier to effective counseling in relation to issues of race, ethnicity, culture, religion, sexual orientation, and gender. However, very little attention has been paid to clinician bias in relation to social class. One such study conducted in Britain (Balmforth, 2009) focused on social class and counselor bias by interviewing seven counselors about their experiences as clients. The researcher found that power dynamics played a significant role in the clients’ perceptions of their counseling experiences when the counselor was perceived to be of higher social standing than the client. In the one case where the client perceived the counselor as of the same social standing, class identity did not seem to be as salient. Further, participants in the study did not perceive their counselors as being aware of their feelings and perceptions about the clinical interactions. For clinicians, the ability to accurately conceptualize the client’s needs is imperative to effective service delivery (West-Olatunji, 2008). This becomes more significant as a correlate to clinician efficacy when considering work with diverse clients. Another study that explored counselor conceptualization skills in relation to social class investigated the relationship between social class and empathy (Kraus et al., 2010). In a sequenced set of three nested studies in which they solicited the responses from university personnel and students, the researchers found that participants from lower-class backgrounds displayed more empathy toward others and incorporated more of an ecological approach to their perceptions of others. Their findings suggest that one’s social positioning may have a significant impact on counselors’ ability to accurately and effectively conceptualize clients’ concerns.

HELPING PROFESSIONALS AND SOCIAL CLASS

Helping professionals’ self-perception as a member of a social class is another area of interest. One of the major tenets of multicultural counseling is the ability to self-reflect about one’s own biases (Arredondo et al., 1996). This assumption about clinician efficacy is based upon the belief that our own lived experiences serve as barriers to first recognizing and then understanding the experiences of others. In the clinical setting, this is paramount given our task of interpreting clients’ histories and hypothesizing about what can transform their current situations into self-actualizing experiences. Over the past 3 decades, the counseling profession, specifically, has made great strides in assisting counselor trainees to become more culturally competent when working with clients who are diverse based upon ethnocultural, religious, ability, gender, and sexual orientation differences. Moreover, counselors have facilitated similar growth in other mental health disciplines with the adoption of the multicultural counseling competencies in psychology, social work, and education, for example. Recently, other competencies have been developed to provide specificity with particular client populations, such as the advocacy competencies (Toporek, Lewis, & Crethar, 2009) and the LGBTQ counseling competencies (Association for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues in Counseling [ALGBTIC], 2010). However, little discussion has focused on self-awareness and social class.

Perhaps helping professionals have been slow in developing discourse around clinicians and social class because of our implicit beliefs about this construct. In the United States, in particular, race and gender are more dominant in our discourse than social class. Part of this is due to socially embedded beliefs about diversity in U.S. society, that any individuals can achieve and advance as far as their talents and industriousness will take them. This is the bootstraps concept wherein hard work and the myth of meritocracy prevail (Sue & Sue, 2008). In other countries, the concept of social class is more visible and accepted in societies. In India, for example, the country continues to struggle with discrimination against Dalits (formerly known as “untouchables”) and has instituted several constitutional provisions to address this social issue (Waughray, 2010). Japan also wrestles with the challenge of confronting socialized beliefs about the barakumin, who are considered to have hereditary underclass status (Yoshino & Murakoshi, 1977). However, it has been suggested that the social silence around social stratification globally is linked to issues of social identity construction (L. Smith, 2010). Thus, there may be some reflexivity between clinicians’ own constructed identities, the issues of systemic oppression, and their inclination to openly discuss their own social identity, social class, and social positioning among peers.

MULTICULTURAL CONCERNS AND SOCIAL CLASS

As clinicians begin to open up the discourse on social class, a major task is to begin framing the discussion beyond the roots of sociological theories to counseling pedagogy. At present, theorizing about social class requires an understanding of complex, multilayered theoretical constructs embedded in 18th-century sociological literature (West-Olatunji, 2010b). Further, what is available in the literature about lower-class individuals for practitioners is often pejorative in nature. Additionally, discussion about social class is still framed within the experiences of mainstream values and does not take into consideration the concerns of women and people of color. More importantly, existing literature on social class is disjointed. Hence, social class scholarship with a focus on women, LGBTQ, disability, and cultural hegemony has been disconnected from the social class discussion. For example, the literature on traumatic stress is used to frame the emotional and psychological effects of systemic oppression and cultural hegemony on historically marginalized groups in the United States. Additionally, much of the foundational discussion on social class has used the intellectualism of European philosophers to the exclusion of female and culturally diverse scholars (Belgrave & Allison, 2006). Finally, womanist scholars have advanced the discussion of intersectionality to highlight the confluence of culture, gender, and class for women of color.

SELF-REFLECTION OPPORTUNITY 1.1

Borrowing from the multicultural counseling competencies (Arredondo et al., 1996), enhancing awareness, knowledge, and skills are useful tools for increasing clinical competence when working with clients of varying social class. Increasing awareness means to focus on one’s own biases in order to: (1) identify and shelve any barriers to the therapeutic alliance and (2) effectively conceptualize the client’s concerns (West-Olatunji, 2008). Table 1.1 reflects four socially embedded messages about social class with examples from the first author’s experiences about these messages.

Now, use Table 1.2 to reflect on your own internalized views about social class. What messages were socially constructed for you? From what institutional sources did these messages emerge? What messages did you receive about these beliefs from your familial system?

Table 1.1 My Socially Embedded Messages About Social Class

Table 1.2 Socially Embedded Messages Exercise

KNOWLEDGE

Our socially embedded perceptions of others often create single stories that lack depth and context. Altering these single stories requires the creation of multiple realities to move beyond our culturally encapsulated beliefs. New knowledge construction is needed to assist the counselor in rescripting old (ineffective) perceptions of the client’s reality. Thus, it becomes important to acquire accurate information about the client’s environmental influences. To begin your investigation to increase knowledge about a particular social class group, watch a movie/film or read a book, and then seek out an opportunity to interact with members. As follow up, reinsert your socially embedded messages from Table 1.2 in the first column of Table 1.3 to document your experiences, then document your experiences in the second column (“Contact”). Provide a brief reflection narrative for each experience.

Table 1.3 My Single Stories: Knowledge Acquisition Exercise

Skill

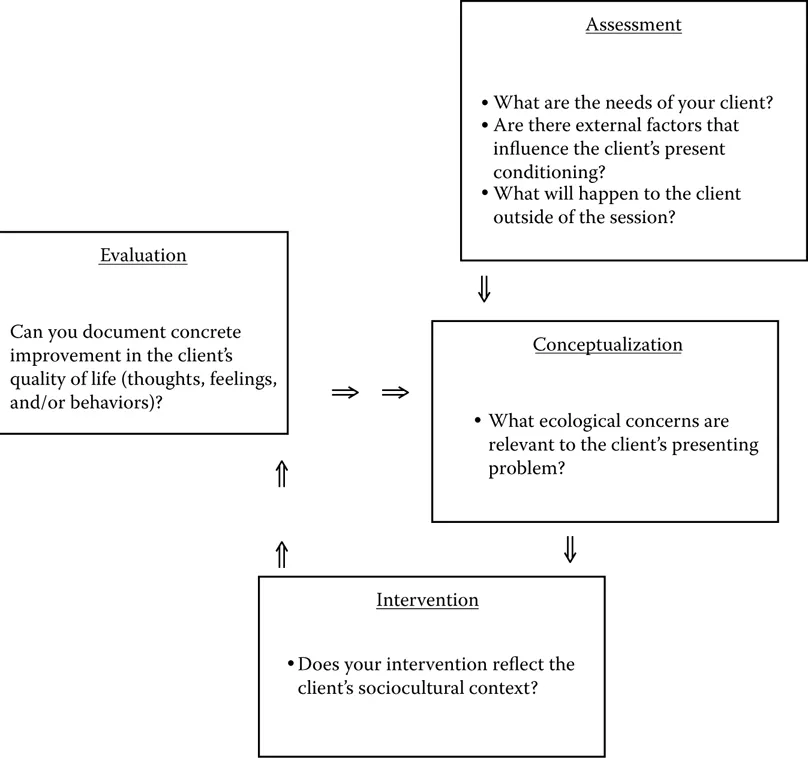

Having awareness about one’s biases and then learning about the lived experiences of others is insufficient alone to significantly impact clinical effectiveness. Increasing clinical skills is the ultimate goal in cultural competence. Thus, it becomes imperative that clinicians change the way in which they practice counseling with clients of varying social classes. Noted below is a self-reflection exercise that focuses on four key phases of clinical activity: assessment, conceptualization, evaluation, and intervention. First, reflect on your experiences with a client in your practice, particularly one who represents a social class group with which you would like to increase your skill level. In each box, document your clinical activity and note how it incorporates your awareness of social class. First, assess the status of your client, then conceptualize the client’s needs, next provide an appropriate intervention, and finally, evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Four phases of clinical activity.

Case Study 1.1: Disasters and Social Class

Nowhere have the issues of disasters and social class been more evident with worldwide implications than during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in the Gulf Coast area, and more particularly, in New Orleans. Shortly after the devastation of the hurricane, the levees broke, causing the massive flooding that forever changed the city of New Orleans. Around the time that Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, I was out of the country providing consultation in Asia. While I had prepared an elaborate training program on multicultural counseling, the participants were far more interested in the post-Katrina events shown on CNN World and other televised news channels. They wanted to know why the U.S. government was not providing immediate rescue and aid to the survivors trapped on rooftops and in attics. I had no easy answers.

In training for disaster response, counselors and other mental health professionals are taught how to assess for the most vulnerable sectors of the community, such as the elderly, children, and those with compromised health conditions, including mental health diagnoses. However, disaster mental health counselors have not been trained to view social class as a vulnerability. Yet, in almost every major natural disaster that has occurred globally, social class has been a factor. Large numbers of individuals from the lower social strata are disproportionately impacted by disasters (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009). This was true during the Kobe (Japan) mudslides in 1995, the tsunami that hit Southeast Asia in 2004, Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005, and the earthquakes of Haiti and Guatemala in 2010.

Why are lower-class communities disproportionately affected by natural disasters? One explanation links substandard housing to poverty. Municipalities tend to build low-income living quarters in geographic locations that are hazardous, unstable, or unprotected from natural forces. Moreover, lines of communication to provide emergency notification and procedures are often either nonexistent or inoperable. Further, individuals from lower classes often lack adequate transportation to leave their communities during a natural disaster. Thus, members of impoverished communities are often at the mercy of natural forces. Without advocacy efforts from within and without, members of lower-class communities continue to experience systemic marginalization and suffer disproportionately during disasters.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In order to change the way in which we practice counseling to address socially embedded norms about social class, it is important that we emphasize the concept of humanism that is a core element of our profession. To be more fully human, we must: (1) move away from our single stories about social class, (2) expand our circle of influence by seeking interactions with those individuals who are outside of our social class group, and (3) challenge false assumptions made by others.

Moving away from the single story requires reflection and critical discourse to challenge our belief systems. This is not an easy task, as we have seen from the previous work of multicultural counseling scholars. Students being trained in helping professions as well as professionals alike struggle with adopting new attitudes and beliefs about diverse groups of people. Restorying about social class will be no different, and perhaps even more difficult. However, what we have learned from the historiography of multicultural counseling is that we can (and do) rescript, relearn, and retool to more effectively serve culturally diverse clients. With the advancement of counseling in a global context, the 21st century allows the profession to learn from developing counseling programs in Asia, Eastern Europe, and southern Africa (Portal et al., 2010). Counselors and counselor educators in the global arena show promise as potential leaders of the discussion on counselors and social class, given the salience of social class outside of the United States. The American Counseling Association and other international counseling organizations, such as the International Association for Counselling, need to develop an international agenda that actively promotes international dialogue about social class. The venue could be both face-to-face and digital to allow for greater participation worldwide. Additionally, international organizations need to augment publishing opportunities for international scholars to di...