eBook - ePub

The Routledge Companion to Fair Value and Financial Reporting

Peter Walton, Peter Walton

This is a test

Share book

- 406 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Routledge Companion to Fair Value and Financial Reporting

Peter Walton, Peter Walton

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Comprising contributions from a unique mixture of academics, standard setters and practitioners, and edited by an internationally recognized expert, this book, on a controversial and intensely debated topic, is the only definitive reference source available on the topics of fair value and financial reporting.

Drawing chapters from a diverse range of contributorson different aspects of the subject together into one volume, it:

- examines the use of fair value in international financial reporting standards and the US standard SFAS 157 Fair Value Measurement, setting out the case for and against

- looks at fair value from a number of different theoretical perspectives, including possible future uses, alternative measurement paradigms and how it compares with other valuation models

- explores fair value accounting in practice, including audit, financial instruments, impairments, an investment banking perspective, approaches to fair value in Japan and the USA, and Enron's use of fair value

-

An outstanding resource, thisvolume is an indispensable reference that is deserving of a place on the bookshelves of both libraries and all those working in, studying, or researching the areas of international accounting, financial accounting and reporting.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Routledge Companion to Fair Value and Financial Reporting an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Routledge Companion to Fair Value and Financial Reporting by Peter Walton, Peter Walton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Section II

Theoretical Analysis

6

Recent History of Fair Value1

David Alexander

Introduction

This chapter is about fair value as defined by IASB. It is not about fair value as a shorthand and ill-defined euphemism for current values (plural), this being the sense used in some other chapters. The contrast between these two ways of thinking can be usefully explored by first of all thinking of the theoretical array of valuation possibilities, and then by considering the IASB definition of fair value and its implications.

Towards a Theoretical Framework

This section provides an analytical framework of value concepts within which the later discussion of fair value can be embedded. This closely follows, but is significantly extended from, the work of Edwards and Bell (1961).

Edwards and Bell invite us to consider a semi-finished asset (i.e. part-way through the production process) to enumerate the various dimensions through which we can describe this asset, and thus to calculate and define all the possible permutations arising from this multidimensional consideration.

Three dimensions are suggested:

- the form (and place) of the thing being valued;

- the date of the price used in valuation;

- the market from which the price is obtained.

The form can be of three types. First, the asset could be described and valued in its present form (e.g. a frame for a chair). Second, it could be described and valued in terms of the list of inputs (e.g. wood, labour, its initial form). Third, it could be described and valued as the output it is ultimately expected to become, less the additional inputs necessary to reach that stage (e.g. a chair less a padded seat). This last can be described as its ultimate form.

The date of the price used in valuation, when applied to any of the above three forms, itself gives rise to three possibilities – past, current and future. We can talk about past costs of the initial inputs, current costs of the initial inputs, or future costs of the initial inputs. We can talk about past costs of the present form (i.e. what we could have bought it for in the past as bought-in-work-in-progress), about current costs of the present form, or about future costs of the present form. Finally, the prices assigned to the asset in its ultimate form (and to the inputs which must be deducted) could also bear past, current or future dates.

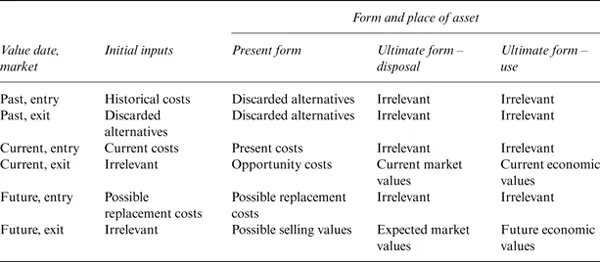

Table 6.1. An array of value concepts

Source: Edwards and Bell (1961); last column: author

The above yields nine possible alternatives for the asset. But we have still to consider the third dimension – the market from which the price is obtained. Two basic types of market need to be distinguished: the market in which the firm could buy the asset in its specified form at the specified time, giving entry prices, and the market in which the firm could sell the asset in its specified form at the specified time, giving exit prices. Adding this third dimension with its two possibilities leads to a total of 18 possible alternatives for the asset. This is as far as the Edwards and Bell analysis went. But the ‘ultimate form’ column needs to be further divided to allow for valuation through usage, as well as valuation through disposal, i.e. to embrace economic value as well as the various market exit prices. To extend the chair illustration, one possible course of action with a partly completed chair is to complete it and hire it out for rental, or to allow the managing director to sit on it while at work (in which case it becomes part of a ‘cash-generating unit’ (IAS 36 para 5, 1998, para 6, 2004). This adds a further six possible alternatives for the asset, making 24 in all. These are shown in Table 6.1. Note that, strictly speaking, columns 1 and 2 need to be further divided in the same way, but none of the additional 12 theoretical possibilities will be relevant to rational decision-making, so this complication is ignored here.

The meaning of each of these 24 value concepts might be articulated as shown in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2. Suggested articulation of the 24 concepts from Table 6.1

| Initial inputs | |

| Past, entry | Original costs of raw inputs. |

| Past, exit | Past selling prices of those raw inputs in their raw form. |

| Current, entry | Cost of those raw inputs. |

| Current, exit | Today’s potential selling price of those raw inputs if still in their original form (which they are not). |

| Future, entry | Expected future costs of those same raw inputs in their original form. |

| Future, exit | The expected future selling price of the raw inputs if still in their original form (which they are not). |

| Present form | |

| Past, entry | The past cost at which the product could have been purchased in its present partially completed form (it was not). |

| Past, exit | Past selling prices at which the product could have been sold in its present partially completed form (but it was not). |

| Current, entry | The cost at the present time of buying the asset in its present partially completed form. |

| Current, exit | Today’s selling price of the product in its present partially completed form. |

| Future, entry | The expected future cost of buying the asset directly from a supplier in its present partially completed form. |

| Future, exit | The expected future selling price of the product in its present partially completed form. |

| Ultimate form | |

| Past, entry | The past cost at which the product could have been purchased directly from a supplier in its final fully completed form (but it was not). |

| Past, exit | The past selling price at which the product could have been sold in its final fully completed form (if we had had the product in that form, which we did not). |

| Current, entry | The cost at the present time of buying the product in its final fully completed form (which we did not). |

| Current, exit | Today’s selling price of the product in its final fully completed form. |

| Future, entry | The expected future cost of buying the product directly from a supplier in its final fully completed form. |

| Future, exit | The expected future selling price of the product in its final fully completed form. |

| Ultimate form – Usage | |

| Past, entry | The past cost at which this or an alternative sit-on-able resource could have been purchased directly from a supplier in fully usable form (but it was not). |

| Past, exit | The past selling price of the stream of net benefits from this or an alternative sit-on-able resource (but we did not sell it). |

| Current, entry | The cost at the present time of buying the stream of net benefits (which we did not). |

| Current, exit | The selling price today of the stream of net benefits from this or an alternative resource. |

| Future, entry | The expected future cost of buying the stream of net benefits. |

| Future, exit | The expected future selling price of the stream of net benefits from this or an alternative resource. |

Source: Author

Edwards and Bell choose a subset of the alternatives in Table 6.1 for their own detailed theoretical development and appraisal. The purpose in this chapter is different and no comparative appraisal is attempted here (but see also Chapter 11).

It should be noted that current economic value, as the term is used in Tables 6.1 and 6.2, is the same, ignoring transaction costs, as the concept implicit in Hicks’ famous Income No. 3 (Hicks, 1946). This is defined as follows:

Income No. 3 must be defined as the maximum amount of money which the individual can spend this week, and still expect to be able to spend the same amount in real terms in each ensuing week.

Fair Values

There is overwhelming evidence that IASC/B is favourably disposed towards the use of fair values, defined in 1982 in the then version of IAS 20 as: ‘the amount for which an asset could be exchanged between a knowledgeable, willing buyer and a knowledgeable, willing seller in an arm’s length transaction’ and in the current IASB Glossary as: ‘the amount for which an asset could be exchanged, or a liability settled, between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm’s length transaction’.

Fair value is a central concept in all the last three Standards issued by the old IASC, i.e. IASs 39, 40 and 41. Since the advent of the IASB in 2000, the onward march of the fair value concept has continued apace. The concept is included in the definitions section of IFRS 2, IFRS 3, IFRS 4 and IFRS 5. IFRS 7 cross-references the reader to the IAS 39 definition, and IFRS 6 allows the use of the revaluation model in IAS 16. Resistance to the concept has also been strong, as will be discussed briefly later in this chapter and in more detail elsewhere in this volume, such as Chapters 18 and 19. The new single statement of financial performance towards which IASB, FASB and others are working is clearly designed to facilitate reporting under a fair value world. It is not yet officially in the public domain, even in draft, but see Barker (2004). Notwithstanding these anticipated developments, the emanation of the fair value concept seems to have occurred more or less spontaneously, and certainly more or less haphazardly, over the past couple of decades, with no clear theoretical foundations (Warrell, 2002).

Over the years, the IASC has given a number of slightly different definitions of fair values, which are shown in detail in Table 6.3.

Table 6.3. IASB definitions of fair value

| 16.6 | Fair value is the amount for which an asset could be exchanged between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm’s-length transaction. | 1998 (and 1993) |

| 17.3 | Fair value is the amount for which an asset could be exchanged or a liability settled between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm’s-length transaction. | 1997 |

| 18.7 | Fair value is the amount for which an asset could be exchanged, or a liability settled, between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm’s-length transaction. | 1993 |

| 19.3 | Fair value is the amount for which an asset could be exchanged or a liability settled between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm’s-length transaction. | 1988 |

| 20.3 | Fair value is the amount for which an asset could be exchanged between a knowledgeable, willing buyer and a knowledgeable, willing seller in an arm’s-length transaction. | 1982 (Ref. 1994) |

| 21.7 | As 18.7 | 1993 |

| 22.8 | As 19.3 | 1998 (and 1993) |

| 25.4 | As 20.3 | 1985 (Ref. 1994) |

| 32.5 | As 18.7 | 1998 (and 1995) |

| 33.9 | As 18.7 | 1997 |

| 38.7 | Fair value of an asset is the amount for which that asset could be exchanged between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm’s-length transaction. | 1998 |

| 39.8 | ‘As IAS 32’, i.e. as 18.7 | 1998 |

| 40.4 | As 16.6 | 2000 |

| 41.8 | As 18.7 (but see also 41.9, as in note 2 below) | 2001 |

| Glossary | As 18.7 | 1999 |

Source: Extracted from published accounting standards

Notes

- Paragraph numbers are shown on the left and the year of publication is shown on the right. Ref. is short for reformatted.

- 41.9: The fair value of an asset is based on its present location and condition. As a result, for example, the fair value of cattle on a farm is the price for the cattle in the relevant market less the transport and other costs of getting the cattle to that market.

- All definitions, except the glossary, are explicitly stated to apply ‘in this Standard’.

- The earlier version of the definition, as quoted here for 20.3, was also used in earlier versions of other standards, i.e. 16.6 (1982)17.2 (1982)18.4 (1982)22.3 (1983)

Fair Value in a Non-IAS Context

There seems to be a tendency to use the phrase ‘fair value’ as a loose term for market or current value, as, for example, in Richard (2002). A number of these looser interpretations are explored elsewhere in this book. The relationship between the continental traditions (Savary, Schmalenbach; see e.g. Richard, 2002) and more recent regulatory approaches is not pursued here. However, US usages of the ‘fair value’ term are worth exploring, essentially because early usage did not necessarily seem to equate with the IASC use of the term, and considerable confusion could result.

A number of references to fair value in US regulation have surfaced (see Note 1). The earliest found is in ARB 43, on quasi-reorganization or corporate readjustment (1939–1953), but no clear definition is even implicit. APB 29, Accounting for Nonmonetary Transactions (1973), takes an exit value slant, but whether net or gross is unclear from the statement given:

Fair value of a nonmonetary asset transferred to or from an enterprise in a nonmonetary transaction should be determined by referring to estimated realizable values in cash transactions of the same or similar assets, quoted market prices, independent appraisals, estimated fair values of assets or services received in exchange, and other available evidence. If one of the parties in a nonmonetary transaction could have elected to receive cash instead of the nonmonetary asset, the amount of cash that could have been received may be evidence of the fair value of the nonmonetary assets exchanged.

SFAS 35, Accounting and Reporting by Defined Benefit Plans (1980), gives a definition in the Standard (but not in the glossary), which is essentially net realizable value:

Plan investments, whether equity or debt securities, real estate, or other (excluding contracts with insurance companies) shall be presented at their fair value at the reporting date. The fair value of an investment is the amount that the plan could reasonably expect to receive for it in a current sale between a willing buyer and a willing seller, that is, other than a forced or liquidation sale. Fair value shall be measured by the market price if there is an active market for the investment. If there is not an active market for an investment but there is such a market for similar investments, selling prices in that market may be helpful in estimating fair value. If a market price is not available, a forecast of expected cash flows may aid in estimating fair value, provided the expected cash flows are discounted at a rate commensurate with the risk involved. For an indication of factors to be considered in determining the discount rate, see APB Opinion No.21, Interest on Receivables and Payables. If significant, the fair value of an investment shall reflect the brokerage commissions and other costs normally incurred in a sale.

SFAS 67, Accounting for Costs and Initial Rental Operations of Real Estate Projects (1982), gives a formal definition, which is obviously an exit value, and arguably implicitly net rather than gross:

The amount in cash or cash equivalent value of other consideration that a real estate parcel would yield in a current sale between a willing buyer and a willing seller (i.e., selling price), that is, other than in a forced or liquidation sale. The fair value of a parcel is affected by its physical characteristics, its probable ultimate use, and the time required for the buyer to make such use of the property considering access, development plans, zoning restrictions, and market absorption factors.

SFAS 80 (1985) refers to fair values of hedged items but gives no definition. Finally, SFAS 87 (1985) gives a formal definition in its glossary which is definitely a net realizable value concept:

The amount that a pension plan could reasonably expect to receive for an investment in a current sale between a willing buyer and a ...