2

New Wine in Old (?) Bottles: Leadership

and Personnel Changes

“A new broom sweeps clean “

—Anonymous

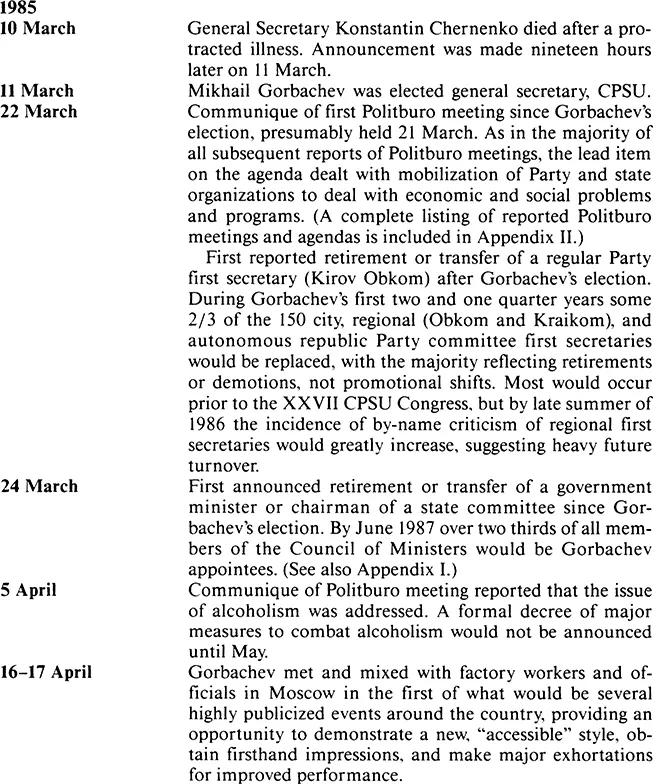

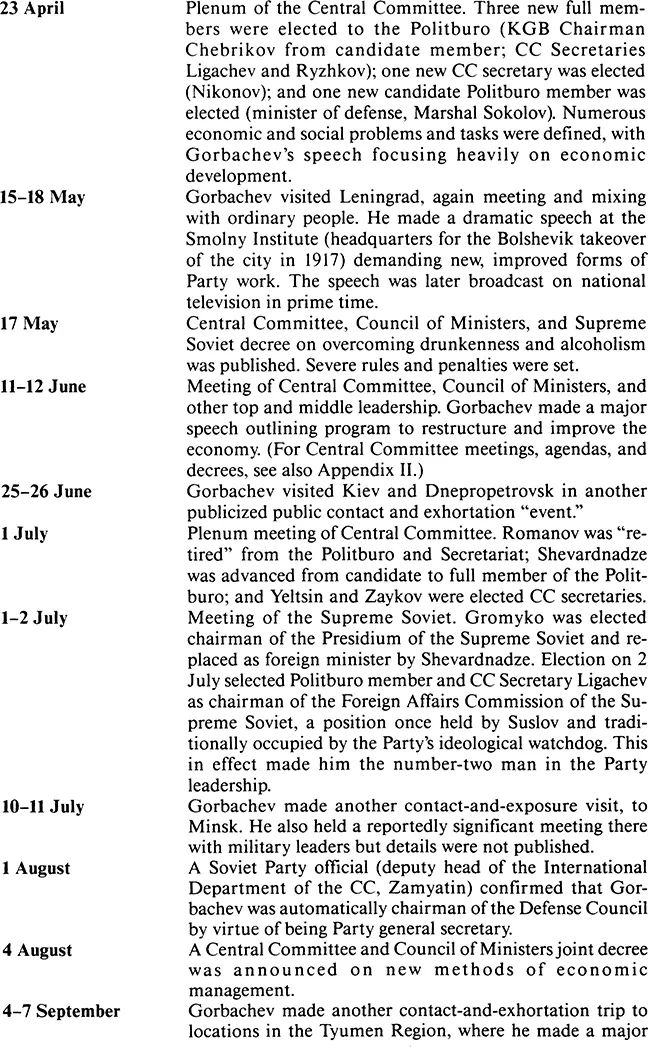

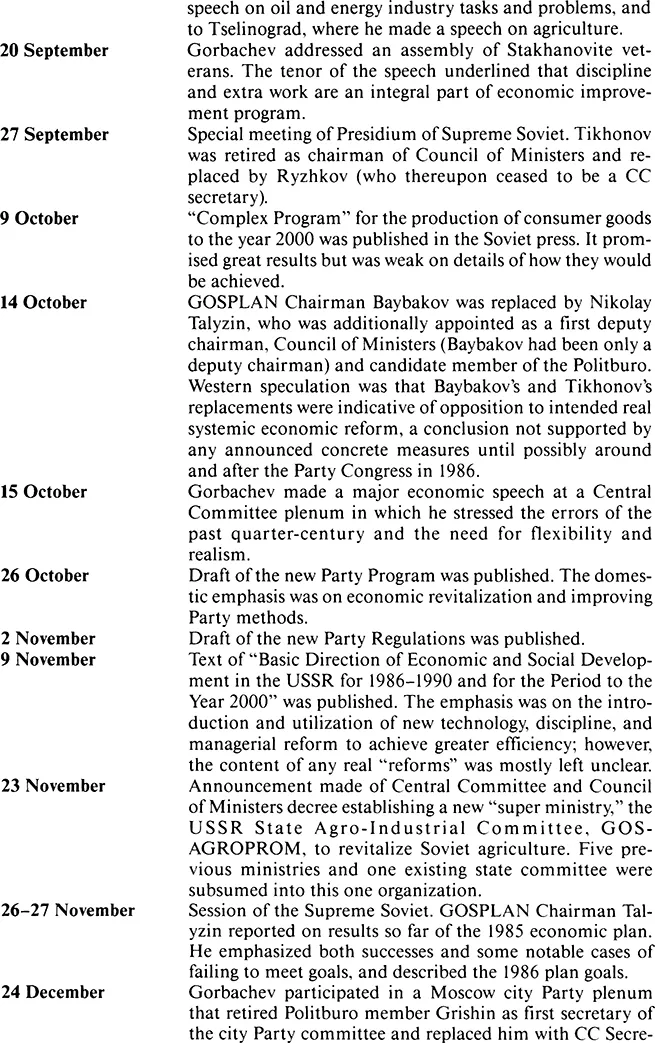

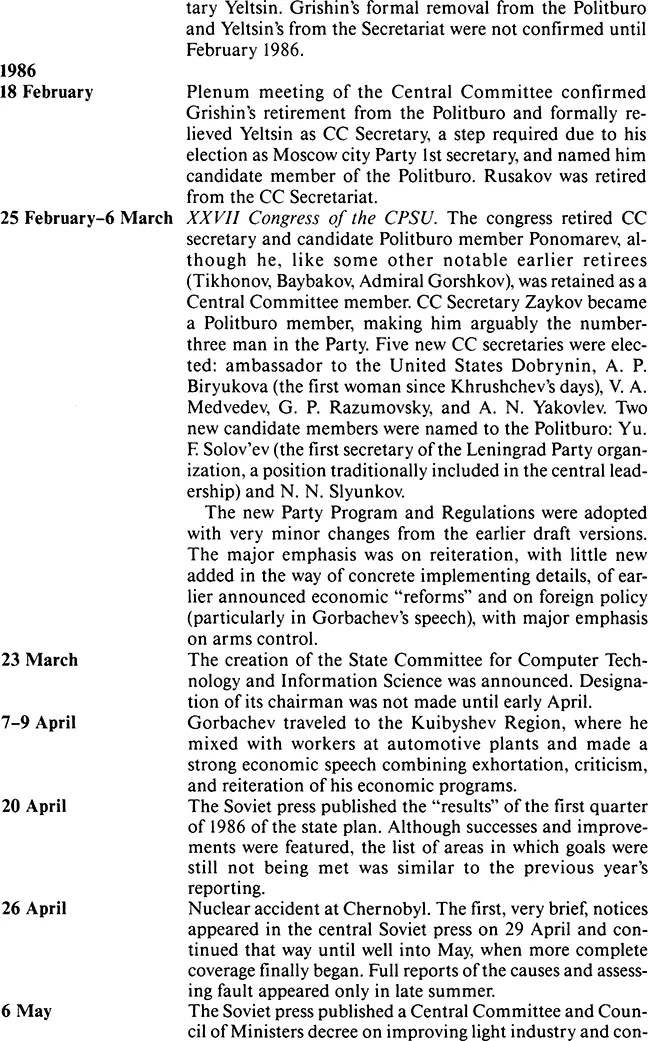

The main problem confronting the new general secretary of the Central Committee (CC) of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was that of real, assured power. Being chosen general secretary was only the prelude to ruling. To become a real ruler, Gorbachev had to consolidate and ensure his position in the Politburo and the CC Secretariat. The dialectics of the Soviet system require that a new general secretary free himself both from his political rivals, because they may prevent the realization of his ambitions, and from those who supported his rise to power, because they may limit his independence of action. Indeed, this is how Gorbachev began: he rid himself of dependence on both enemies and friends. Only by eliminating this double dependence can a general secretary proceed to the implementation of his political, social, and economic goals.

For Gorbachev, the transitional period lasted only one year, and was really accomplished at the national level in a much shorter time. This was a record. But he owed the accomplishment not only to his talents but also to an auspicious configuration of forces in the Kremlin. The death of three successive general secretaries in the course of two and a half years had undermined political alliances within the Politburo.

Throughout Gorbachev’s time as Soviet leader, all of his actions, including foreign policy initiatives, administrative reorganizations, the shakeup of the bureaucracy, and the various social campaigns, can be best understood in the context of his struggle for the consolidation and retention of power. The decisions a new general secretary makes and the policies he embarks upon can be linked to his need of advancing “his” people to higher positions of power, Everything else he does is of secondary importance. The period of genuine policy-making on Gorbachev’s part could not really begin until the apparatus to carry out his policies in exact conformity with his political preferences and personal ambitions was in place.

Gorbachev first needed two things: a set of issues to justify wholesale changes at the top and all through the system, and a safe working majority in the central leadership. The issues were ready-made in the economic, social, and foreign policy drift of recent years. Gorbachev had already, in December 1984, associated himself with a policy aimed at “an intensive, highly developed economy.” A campaign against corruption had been used by Andropov and given lip service by Chernenko as a vehicle for shaking up the bureaucracy, and a campaign against alcoholism was a handy tool for promoting social change. Moreover, because these involved real issues facing the USSR, if Gorbachev wanted eventually to introduce any radical or fundamental changes in order to solve them, he had to first ensure his absolute power base.

Before Gorbachev could move concretely on any issue, he had to shore up a very slim majority in the Politburo. He did this in April when he brought the Andropov-appointed CC secretaries, Ligachev and Ryzhkov, to full Politburo membership without their even having been candidate members. At the same time he reensured the support of the KGB by elevating Andropov’s man, Chebrikov, from candidate to full member. He mollified the defense establishment for his intended sacking of Romanov by making Defense Minister Sokolov a Politburo candidate member. Ligachev and Ryzhkov were excellent illustrations of his preference for promoting men who had demonstrated great success in regional work; Ryzkhov, in fact, had his primary professional working background in industry as an engineer, manager, and planner rather than in Party work.

All of these Politburo appointments, except that of Sokolov, were made from among men whom Andropov had brought to central leadership prominence. Gorbachev was not yet in a position to bring his own people into the central leadership in any numbers. For that, he was in too early a stage in the struggle for power; he was completing the consolidation of power by the Andropov group, but was doing so in a way that would make some of them fully his protégés and so that he could later isolate others. The only exception at this time, April 1985, was the appointment of the new CC secretary in charge of agriculture, Nikonov, a career agricultural specialist who had long, close ties to Gorbachev.

With his Politburo majority shored up, Gorbachev was in a position to be much more openly critical of the economic failures of the old guard. More important, he was now in a position both to axe his principal former rival and to move to isolate supporters who had accumulated too much independent power. The convening of the Supreme Soviet at the beginning of July and the concurrent plenum meeting of the Central Committee provided the opportunity.

Grigori Romanov, who had only recently collided with Gorbachev in the struggle to succeed Chernenko, was ousted from his positions in the Politburo and Secretariat, and pensioned off. In a very different manner, Gorbachev’s ideologically compatible friend and supporter in his bid for power, Gromyko, was removed from active political life. The new leader was beginning to distance himself from those to whom he was indebted. Gromyko relinquished his post as foreign minister and was promoted to chairman of the Supreme Soviet. Although according to the Soviet Constitution this post entails significant responsibilities, in fact it is largely ceremonial. By this move, Gorbachev opened up the foreign policy field for himself.

From then on Gorbachev would both set priorities in Soviet foreign policy and determine the means for their realization. He needed, however, to find a nominal head for the foreign policy establishment and there was no appropriate candidate, i.e., one who would be totally subservient and dependent upon Gorbachev, in the Moscow political deck. Therefore, he settled upon a member of the republic nomenklatura, the first secretary of the Georgian republic Central Committee, Eduard Shevardnadze, and promoted him to full membership in the Politburo. Shevardnadze was chosen for several obvious reasons. First, he was dynamic, comparatively young, fairly well educated, and experienced as an administrator. In Georgia he had risen to prominence rapidly. In the 1950s he was secretary of the Central Committee of the Komsomol; from the mid-1960s he was republic minister of internal affairs; and from 1972, first secretary of the republic Central Committee. During his career he had gained a reputation for his uncompromising fight against corruption. This provided a second reason for his promotion, for evidently Gorbachev had decided to conduct a thoroughgoing purge of personnel in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs under the pretext of rooting out corruption in the diplomatic milieu. A third possible reason could have been Gorbachev’s desire to make a positive impression on Western public opinion by giving the appearance that Soviet policy is made not just by Russians but also by members of the other nationalities. This goal could be achieved if the West did not realize that Shevardnadze’s functions would be confined to executing policy, not making it.

At the same time, the CC Plenum “elected” two new members of the Secretariat. Lev Zaykov had succeeded Romanov as Leningrad first secretary when the latter moved to Moscow and was reportedly on very good personal terms with Gorbachev. Now Gorbachev made him Romanov’s replacement as the CC secretary supervising defense. It was a very adroit move, for it appeased the powerful Leningrad regional Party organization while allowing Gorbachev to put his own man there, and it also contributed to the expansion of Gorbachev’s team in the central leadership. Significantly, Zaykov later—at the XXVII CPSU Congress in 1986—became virtually the number-three man in the Party, behind Gorbachev and Ligachev. At the same time Gorbachev brought Boris Yeltsin to Moscow as the CC secretary in charge of construction. Yeltsin was another member of Kirilenko’s old entourage, which had been so effectively coopted by Andropov in his defeat of Chernenko. As it turned out, Yeltsin’s appointment to the Secretariat was only an interim step in the replacement of another of Gorbachev’s former rivals, Grishin. With these changes, Gorbachev had assured an absolute majority of supporters in both the Politburo and the CC Secretariat.

Following these moves to restructure the central Party leadership, the Gorbachev team began to move more virorously to bring new blood into government ministries and into regional Party first-secretary posts. In addition to Shevardnadze, five new ministers were appointed in July, bringing the total to nine since Gorbachev became general secretary. Meanwhile, through the summer the total of new regional first secretaries replaced since Gorbachev had succeeded Chernenko rose to at least twenty-two. To this list of regional satraps selected or approved by Gorbachev should be added an even larger number appointed before his rise to the supreme leadership, when he was Party secretary for cadres, i.e. in charge of personnel appointments.

Also in July two major personnel changes in the armed forces leadership were announced. This was done “through the back door,” i.e. via answers to questions at press conferences, as befits the tradition of Soviet uncom-municativeness in direct official, publicized announcements about senior military command changes. A new commander in chief of the strategic rocket forces and a new head of the main political administration of the armed forces were installed. In diplomatic scuttlebutt this was widely reported to have been due to the incumbents’ opposition to Gorbachev’s plans for wide-ranging arms control proposals. Such a version cannot be precluded, but the more important of these changes in such a regard, the retirement of Marshal Yepishev, the army’s political watchdog, was officially attributed to health and, in fact, he died only two months later. Moreover, as will be discussed in subsequent chapters, neither the extent of Gorbachev’s arms control proposals nor any real indications of military disapproval had at this time reached the proportions that they did later.

The Gorbachev team was at this stage in a position to speak with increasing openness about past failures, to begin to propose new reforms, and to emphasize new foreign policy lines. These proceeded mostly in generalities whose real content would remain unclear into the fall. Then in September the axe fell on the most senior remaining member of the Brezhnev-Cher-nenko team, the eighty-year-old chairman of the Council of Ministers (the official Soviet “premier”) Nikolai Tikhonov. Tikhonov was replaced by Gorbachev’s man Nikolai Ryzhkov, who epitomized the type of officials favored by the new general secretary: those who had demonstrated technical competence in a successful regional post, were loyal to him, and were likely to be willing to undertake innovative approaches to “get the job done.” If one assumes that Tikhonov’s departure was not mainly, or at least not only, due to age and illness, it appears to have three possible explanations. First, it may have been simply part of the consolidation of Gorbachev’s personal power, although this could have awaited a more fitting time, such as at or just before the Party congress. Second, and most likely, it was related to economic plans, with the young (only fifty-six years old) and dynamic Ryzhkov’s being appointed to carry through economic reforms that Gorbachev hoped to pursue. Even if major changes were not intended, Ryzhkov’s appointment contributed to the appearance of the new vigor necessary for psychological impact if the program for reform was to be mostly only window dressing and a combination of exhortation and discipline. A third reason for the timing may have been to show the West, on the eve of Gorbachev’s visit to France, that the new leader was firmly in control, with the struggle-for-power stage already behind him.

The economic explanation became more compelling when Tikhonov’s replacement was followed in early October by the sudden resignation of a key economic planner, the chairman of the State Planning Committee (GOSPLAN) and deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers, N. K. Baybakov, who had held this key post almost twenty years! Moreover, Baybakov’s replacement, Nikolai Talyzin, was made a first deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers and a candidate member of the Politburo, positions his predecessor had never held.

In the same vein, the rest of the year saw a turnover in the state apparatus that was virtually unprecented in both scale and rapidity. In the last three months of 1985 Gorbachev removed five of the then eight deputy chairmen of the Council of Ministers, appointed two new first deputy chairmen (out of then four), and removed twenty-two USSR ministers or chairmen of state committees. Of the latter, fourteen were directly replaced, including two who were simultaneously deputy chairmen of the Council of Ministers; the other eight were heads of ministries or state committees that were abolished as separate entities and subsumed into two new larger ones. In January primarily, and also in February, prior to the Party Congress, this pace continued with nine more such changes being announced.

The Gorbachev axe also fell on more of the old guard in the Politburo and Secretariat. Erstwhile rival Grishin was sacked as first secretary of the Moscow city Party organization in December. In February the formality of removing him from the Politburo was completed when Gorbachev’s protégé Yeltsin moved from the Secretariat to become a candidate member of the Politburo as well as, from December, first secretary of the Moscow organization. At the same time another Brezhnev era CC secretary, Rus-akov, was retired.

During these months leading up to the Party Congress, the Gorbachev machine was also busy restaffing the regional Party organizations. Four more republic Party first secretaries were named (a replacement for Shevardnadze in Georgia had been announced after the former had become full Politburo member and minister of foreign affairs), and at least another 24 regional (Obkom) first secretaries were appointed. In fact, just before the Congress a senior Party figure was quoted as stating that some 23 percent of the heads of the 430,000 primary Party organizations, or some 100,000 functionaries, had been replaced. Meanwhile, prior to the Congress some nine heads of the key CC departments had also been replaced.

The winter of 1985-86 also saw another key change in the top military leadership. Fleet Admiral Gorshkov, who had led the Soviet navy for almost thirty years, was unceremoniously retired and replaced by his deputy, Admiral Chernavin. Gorshkov could well have been retired primarily due to age; however it cannot be discounted that as with the military leadership changes in July, there may have been other factors involved. If the military was slated to lose some of its traditional priority claim on Soviet resources—an assumption that is still not fully confirmed—the influential and combative Gorshkov may have had to be replaced because unlike the other leaders in the Ministry of Defense, he was less willing to accept cutbacks docilely. It may also be significant that in addition to the two service commanders in chief (Gorshkov and Tolubko, the former commander in chief of the strategic rocket forces) and the head of the military political administration (Yepishev), there appears to have been an unusually high turnover of major operational commanders in the Soviet armed forces under Gorbachev. Moreover, this turnover again reached the level of deputy, and even first deputy minister of defense in late summer 1986, when a few other, more persuasive indications of concern with military ranks over the directions of Gorbachev’s economic and arms control policies began appearing. Finally, in mid-1987, Gorbachev installed his “own” new minister of defense. (These changes will be discussed in greater detail in chapter 12.)

At the Congress itself the process of Gorbachevization of the leadership continued in a dramatic fashion. Zaykov, a Gorbachev appointment to the Secretariat, became the third individual to be simultaneously a full Politburo member and a Party secretary. Five new Party secretaries were “elected”: A. P. Biryukova from the trade union organization, the first woman since Khrushchev’s time; A. F. Dobrynin, the long-time ambassador to the United States; V. A. Medvedev, the head of the Science Department of the Central Committee; G. P. Razumovskiy, an Obkom first secretary; and A. N. Yakovlev, a Gorbachev adviser who earlier was ambassador to Canada. At the same time Boris Poriomarev, the longtime head of the key International Department of the CC, was removed from both the Secretariat and from candidate membership in the Politburo. Two new candidate Politburo members were also appoined: Yu. F. Solov’ev, the first secretary of the Leningrad Obkom; and N. N. Slyunkov, the first secretary of the Byelorussian Party Similarly, 147 (i.e., almost half) of the Central Committee full members were new.

As a result of these changes, five of the twelve full Politburo members were Gorbachev appointees, and either two or three more were staunch Gorbachev loyalists. (The third of these, Gromyko, was originally a full Gorbachev supporter, but in that he has increasingly been shunted into relative impotence, he could now conceivably be no longer as zealous a Gorbachev loyalist as before.) One more (Aliev) is a weathervane who can be counted upon to go with the prevailing winds. The remaining two— Shcherbitskiy and Kunaev—were Brezhnev-era holdovers. They were both regional leaders often away from Moscow and the day-to-day decisionmaking, and both came increasingly under heavy clouds for corruption and inefficiency in their home bases. In fact, at the end of 1986 the axe fell on the more vulnerable of these two old Brezhnev cronies. Kunaev was ousted as first secretary of the Kazakh Party and replaced not by another Kazakh but by a Russian. His removal from the central leadership was then only a formality. In January 1987 he was stripped of his Politburo membership and in June of Central Committee membership. Shcherbitskiy held on through 1986 and the first half of 1987, but he was obviously under fire. He walked a more careful line, but the Ukraine with its long history of nationalism and its vital position in the Soviet economy was a much stronger base of localism (mestnichestvo) than Kazakhstan in the overall all-Union scheme of things.

To return to spring of 1986, after the Party Congress five of the candidate Politburo members and seven of the CC secretaries were then Gorbachev appointees; an additional secretary, although not appointed by Gorbachev, was, after all, Gorbachev’s number-two associate and close colleague, Ligachev. With such majorities, and with at least half of all ministries and state committees—including a majority of the most important ones— headed by his appointees, along with an absolute majority of his men in the Presidium of the Council of Ministers, there was then nothing to prevent Gorbachev from introducing almost any reforms or new directions that he wished. By spring of 1986, one short year after his election as general secretary, Gorbachev had essentially ensured his control over the senior echelons of both the Party and state.

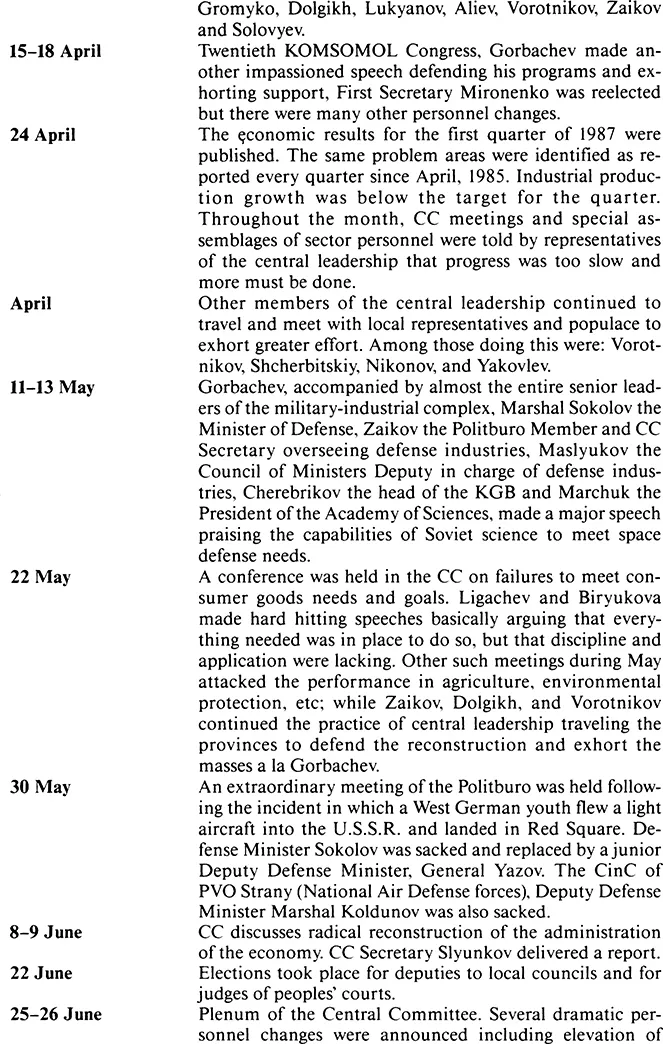

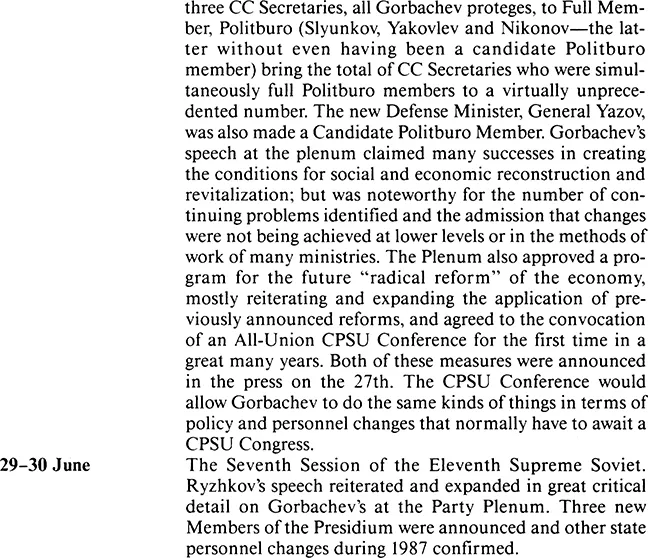

He had also appointed at least half of the city, regional (oblast) and territorial (krai) Party committee first secretaryships. But here he evidently still faced problems, problems not so much of conscious or organized opposition but of immobilism and unwillingness or inability to adapt to the new ways he was preaching. As discussed in the next chapter, throughout the period after the XXVII Party Congress the main themes of the Gorbachev leadership and of the Soviet press turned to the need to root out entrenched re...