eBook - ePub

Prism and Lens Making

A Textbook for Optical Glassworkers

Twyman F

This is a test

Share book

- 640 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prism and Lens Making

A Textbook for Optical Glassworkers

Twyman F

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Prism and Lens Making: A Textbook for Optical Glassworkers, Second Edition is a unique compendium of the art and science of the optical working of glass for the production of mirrors, lenses, and prisms. Incorporating minor corrections and a foreword by Professor Walter Welford FRS, this reissue of the 1957 edition provides a wealth of technical information and hands-on guidance gained from a lifetime of experience. Although some of the techniques have been replaced by more modern methods, this classic book is still a valuable source of practical assistance as well as being a pleasure to read.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Prism and Lens Making an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Prism and Lens Making by Twyman F in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Physics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER 1

HISTORICAL

Ancient Optical Work

1 As with most of the useful arts, the development of lens making has been in an order the reverse of what the scientific man feels to be logical. Instead of first studying the principles of the process, then putting the process into operation, and then finding a use for the product—a course followed by the science-born electrical industry—man first discovered some optical uses of accidentally produced lens-shaped bodies, and only then set himself deliberately to make lenses, leaving till quite recent times the study of the process of lens polishing.

2 It is a pleasing fancy that the possibility of using a lens as a burning glass may be related to the supposed ability of the priestly classes during the Nilotic and Mesopotamian civilizations to “bring down fire from heaven” during religious ceremonies. The word focus (Latin) meant originally a hearth or burning place, and its etymology goes back to roots which suggest that originally it had associations with temple altars or places where sacrifices were burned (see the larger Oxford Dictionary). It may be noted that the modern French word “foyer” is used for both “hearth” and “focus.”

Gunther (1923) points out that in England, the practice of kindling the new fire on Easter Eve by a burning glass was not uncommon in the Middle Ages; an entry to that effect occurs in the Inventory of the Vestry, Westminster Abbey, in 1388.

The references of Pliny and other ancient writers show quite clearly that burning glasses were known to them in the shape of glass spheres filled with water ; and passages from Greek and Roman writers have been cited as showing that they knew of the magnifying properties of lenses, or at least of such glass spheres filled with water. The very thorough account of the subject by (Wilde 1838–43)∗ denies to the ancients all knowledge of spectacle lenses whether for short or long sight, or indeed of any kind of lenses, if we except the spheres of glass filled with water referred to above; and maintains that the lens-shaped glasses or crystals which have been found from time to time among the relics of departed civilizations were made by polishers of jewels for purposes of ornament.Mach (1926), on the other hand, seems to tend, on the whole, to the opinion that a few archaeological objects which have been found were made, and intended to be used, as lenses.

3 Beck (1928) adduces further evidence to show that lens-shaped objects were used as magnifying and burning glasses from very early times. He points out that the usual varieties of glass have been continuously made from the time of the Eighth Egyptian Dynasty, whilst a piece of glass in the Ashmolean Museum is claimed to be First Dynasty, if not pre-dynastic. A large piece of blue glass from Abu Shahrein in Mesopotamia dates from about 3000 B.C. The author continues—

But whatever may have been the original date of the invention of glass we know that by the fourteenth century B.C. there was a well-established centre of glass manufacture in Egypt, and a totally different one in the Aegean, where the technique was in use which did not penetrate into Egypt until a very much later date. Also, although the amount of transparent glass made in Egypt at that time was only a trifling proportion of the total output, much of the Aegean glass was transparent and a considerable amount colourless.

The date of the first manufacture of colourless glass need not however, limit us in finding a possible date for early magnifiers, as crystal was always to hand and the earliest magnifiers known are in that material.

The first reference to a lens that I know of in literature is in The Comedy of the Clouds by Aristophanes, which was performed in 434 B.C. In the second act comes the following passage—

STREPSIADES: You have seen at the druggists that fine transparent stone with which fires are kindled?

SOCRATES: You mean glass?

STREPSIADES: Just so.

SOCRATES: Well what will you do with that?

STREPSIADES: When a summons is sent me, I will take this stone and placing myself in the sun I will, though at a distance, melt all the writing of the summons.

Note.—The point of the remark of Strepsiades in the above passage is that the writing was a summons for debt. Such a writing would be traced on wax, and the suggestion is that, if he melted it with his burning glass, the record would be lost and he would thus be freed from his debts.

… Lactantius in A.D. 303 says that a glass globe filled with water and held in the sun could light a fire even in the coldest weather.

Now lenses sufficiently good to make burning glasses, would make magnifying glasses …

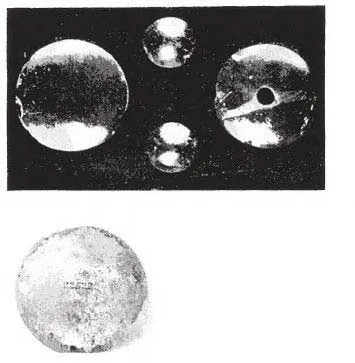

There are in the Egyptian department of the British Museum two magnifying glasses which would make excellent burning glasses, except for the tarnish. They are about 2 in. diameter and about 3 in. focus and would magnify three diameters. They have been ground and are not merely cast. The flat surface has been ground against another flat surface with a rotary motion as at the present. For example; one of these glasses (22522 Egyptian Department) was found at Tanis, and definitely dated A.D. 150. (See Fig. 1.)∗

… but the most conclusive proof as to the early magnifying glasses is the discovery this year (1927) by Mr. E. J. Forsdyke, in Crete, of two crystal magnifying lenses that date back at least as early as 1200 B.C., and probably 1600 B.C., as most of the small objects from the tombs where they were found are of that date.

The author adds finally—

The excellence and minuteness of some of the work in the objects recently discovered by Mr Woolley, and supposed to date before 3000 B.C., make it seem very probable that magnifiers were used, and the fact that crystal was then used makes one hope that further discoveries will enable us definitely to place the manufacture of magnifying lenses, or crystals earlier even than these very important ones just found in Crete.

About half-a–dozen other examples of objects which, whether intended to be used as magnifying glasses or not, were—and indeed, in some cases, are—capable of being so used are given in Chapter 3 of Greeff’s book (1921). One of them is illustrated in Fig. 1. This is in the Volkermuseum in Berlin among the well-known objects excavated at Troy by Schliemann ; it is supposed to date from the second half of the third century B.C. Nevertheless, the author quotes with approval the opinion of Furtwängler (translation) : “That the ancients used magnifying glasses in their work has been asserted and disputed. It cannot be proved, however, much as one may consider it probable.”

It will be seen that the methods of polishing jewels for ornaments were available when men first felt the urge to polish lenses for use. Even then the first use was probably a ritual in connection with religious rather than secular purposes and possibly kept in close secrecy ; a secrecy which still tends to linger in the “mystery” of the trade.

Fig. 1—Ancient optical work

Lens-shaped pieces of rock crystal from ancient Troy.

An early Egyptian lens from Tanis (A.D. 150)

4 The name of Alhazen is often mentioned in connection with the early history of Optics.

Alhazen (Abu Ali Al-Hasan Ibu Alhasan) was born at Basra and died in Cairo in A.D. 1038. He solved the problem of finding the point on a convex mirror at which a ray coming from one given point shall be reflected to another. His treatise on optics was translated into Latin by Witelo (1270) and published by F. Risner in 1572 with the title Optical thesaurus Alhazeni libri VII cum ejusdem libro He crepusculis et nubium ascensionibus (Enc. Brit., 11th Ed., 1910–11, “Alhazen”). The Latin translation will be found in the same volume of the Bulletino di Biographia, etc., as the dissertation of Th. Henri Martin referred to in ref. 1. The only mention Alhazen made of lenses, however, appears to be his statement that if an object is placed at the base of the larger segment of a glass sphere, it will appear magnified.∗

The invention of spectacles

5 We must come to the end of the thirteenth century for the first authentic mention of the use of spectacles, which appears to be that of Meissner (1260–80) when he expressly states that old people derive advantage from spectacles (Bock, 1903).2 In the archives of the old Abbey of Saint-Bavon-le-Grand, the statement is found that Nicolas Bullet, a priest, in 1282 used spectacles in signing an agreement (Pansier, 1901).3 The first picture in which spectacles are known to have appeared is by Tomaso de Modena, in the Church of San Nicola in Treviso, and is of date 1362 (Oppenheimer, 1908). This is illustrated in the Frontispiece.

Martin1 says—

The invention of spectacles for the short and the long sighted is mentioned as a quite recent discovery in a manuscript of 1299 in Florence. Bernard Gordon, Professor at Montpelier, in his work “Lilium medicinae” begun in 1305 alludes to spectacles as a means of remedying visual defects. Giordano da Rivalto, in a sermon given on February 23rd, 1305, remarks that this invention is not yet twenty years old. The man who copied the sermon says he himself saw and conversed with the inventor. Thus it was about 1285—no earlier—that spectacles were invented. We know besides that the inventor was the Florentine, Salvino d’Armato degli Armati, who died in 1317. He hid his secret to keep it as a monopoly. But Brother Alessandro Spina of Pisa, who died in 1313 having seen spectacles made by Salvino d’Armati and having succeeded in making similar ones, hastened to make public the secret. (Translation.)

In a note at the bottom of page 237, Martin states—

Primitive spectacles consisted of two pieces of leather which were fastened on to a cap, worn low over the forehead. (Translation.)

Greeff (1921) has examined a great mass of data about the invention of spectacles. He points out that, although we can scarcely neglect the evidence of pictures, it would be naive to conclude that any spectacles shown were of the epoch the picture represents. Even in depicting very ancient scenes, painters from the time of the van Eycks used to introduce a pair of spectacles to add verisimilitude when they wished to represent a person sunk in study or meditation. The author instances many cases of such anachronisms, for example, Moses is furnished with spectacles in a miniature painted in Heidelberg about 1456. The painter aimed not at historical accuracy in detail, but at representing things as their contemporaries saw and felt them ; spectacles in their pictures were, therefore, of their own period.

In another chapter Greeff examines the suggestions put forward from time to time that spectacles originated in India or in China, but he finds them groundless. He concludes, after citing many authorities, that there is absolutely no evidence that the Chinese had spectacles before they originated in Europe and shows good ground for supposing that they came in through Malacca in the early 16th century. Dr. Greeff attributes, however, to Prof. Hirth of Columbia University, New York, the statement that the Chinese had mirrors both concave and convex, of bronze, in the first century B.C.

It may be accepted, from this and like evidence, that the use of spectacles dates from about A.D. 1280. The picture reproduced in the Frontispiece was not painted from life, since the Cardinal died in 1262 and the picture was painted in 1352.

Brockwell (1948) says—

As for the making of the lenses, Roger Bacon, in his Opus Majus of about 1266, and in his Perspectivae Pars Tertia, showed that “by placing a segment of a sphere on a book with its plane side down, one can make small letters appear large.”∗He communicated his knowledge of optics to his friend Heinrich Goethals, who, travelling in Italy in 1285, handed on his information to Alessandro della Spina, a monk in Pisa, who “could make anything he liked” [operava di sua mano ogni cosa che volesse], and who died in 1313.

6 The present writer has found no account of how lenses were made before William Bourne’s (c. 1585)4 account ; very imperfect, but sufficient to show that processes were then in use very like those still extant. He says (of spectacle lenses)—

These sortes of glasses ys grounde upon a toole of Iron made of purpose, somewhat hollowe, or concave inwardes. And may be made of any kynde of glasse, but the clearer the better. And so the Glasse, after that yt ys full rounde, ys made fast with syman uppon a small block, and so ground by hand untill yt ys bothe smoothe and allso thynne, by the edges, or sydes, but thickest in the middle.

Nothing else is said by him of the materials, tools, or method of working.

Baptista Porta

7 Very different is the account given by Baptista Porta of Naples (1591) in his famous book on Natural Magic—a technical encyclopaedia embracing subjects as diverse as optics, magnetism, cosmetics, cooking, alchemy, pharmacy, and practical jokes. Among much that is trivial, debased and revolting is also to be found much, like his description of optical polishing, which shows a keen quest after knowledge and accurate knowledge of a singularly wide range of subjects. The following extract is from Book 17, Chapter XXI in the English translation published in 1658, but the matter is identical with the Latin edition of 1591. The translation has, however, rendered the original “pilae vitreae”—the phrase employed (as by Pliny) ...