![]()

I

Art and Aesthetics

![]()

1

Aspects of Scientific Discovery: Aesthetics and Cognition

Howard E. Gruber

Teachers College, Columbia University

A cognitive science approach to scientific discovery can be expected to represent the production of a series of problem-solving efforts, a sequence of theoretical models or belief systems, and a series of real-world encounters in which new facts are assimilated into changing mental structures.

But if we want to situate the process of scientific discovery within the context of a purposeful creative life, we need another approach. Indeed, the cognitive sciences most concerned—cognitive psychology, history, and philosophy of science—have no conceptual apparatus and no method for dealing with a creative life. A similar point may also be made about the study of other kinds of creativity.

This situation has led my collaborators and me to devote our energies to the use of the case-study method, to try to reconstruct pictures of creative people at work (Wallace & Gruber, 1989). Each creator is necessarily unique, and it is his or her uniqueness above all that we would like to understand. This is the inescapable task in the study of creative lives. Still, a few common characteristics emerge, providing at least general guidelines for studying the unique creative person.

The Organization of Purpose

One important characteristic of creative work is simply that, being difficult, it generally takes a long time. This prolonged activity requires a powerful organization of purpose to be maintained. Typically, the work of the creator is organized into what we have called a network of enterprise. Although the subjects I have focused on—Charles Darwin and Jean Piaget, among others—have had wide and diversified networks, there is as yet no special theoretical reason to insist that the creator’s network of enterprise must be both wide and diverse.

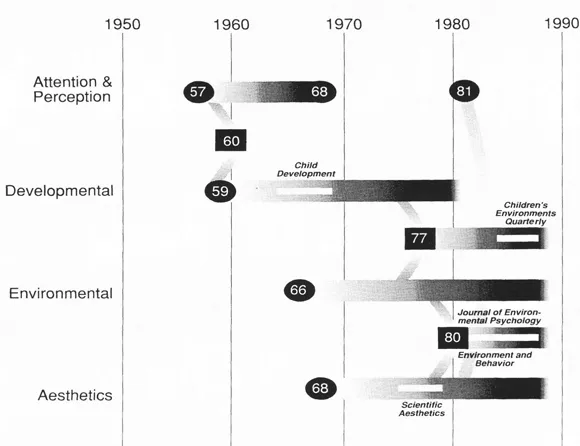

In the case of a productive author, such as Joachim Wohlwill, we can use dates of publication to identify the approximate time of onset, periods of activity, and periods of dormancy of various enterprises. Using journal articles rather than books as indices does not eliminate the error caused by normal publication lags, but it does reduce it. Wohlwill’s network of enterprise can be thus simplified and schematized, as shown in Figure 1.1, into four main areas of activity: general psychology (referring mainly to research on perception and learning), developmental psychology, environmental psychology, and aesthetics. The publication dates of his first papers in each area show the steady, rapid emergence of Wohlwill’s lifetime preoccupations. All four strands of his work make their first appearance in his publications between 1957 and 1968. The most striking points illustrated in the diagram are: (a) the long periods of time in which two or three of these enterprises were pursued in parallel, that is, simultaneously; (b) the various examples of “cross-talk” between the different enterprises; and (c) the explicit quest for unity in his work, reflected in such titles as “The confluence of environmental and developmental psychology: Signpost to an ecology of development?” (Wohlwill, 1980).

Figure 1.1. The network of enterprise of Joachim F. Wohlwill. Note: Year of first publication is several years later than onset of activity in field. White bars indicate time span of service on editorial board of named journal.

In examining other networks of enterprise I have found that enterprises go dormant as a natural consequence of the multiple preoccupations of vigorous, but after all finite, beings, but they rarely die out completely. In Wohlwill’s case, his early interest in the experimental psychology of attention and perception, rather than disappearing, seems to have been assimilated into his other interests; that is, certain experimental methods and attitudes became tools used in pursuing later enterprises. A related facet of his work that does not appear in the diagram is his abiding interest in the methodology of developmental research.

The emergence and development of his various enterprises is reflected also in the professional recognition he received. The diagram shows the periods during which he was on the editorial boards of various journals in three different fields. In each case, as would be expected, this recognition and exploitation of his talents followed, by a few years, his immersion in that field of endeavor.

The question now arises, what motivates the creative person? To some extent we can say that the network of enterprise has motivating power: Tasks undertaken become their own justification, the felt need to complete them the spur. The motivation of work has been described as intrinsic motivation and task orientation, as opposed to ego orientation (Amabile, 1983; Lewin, 1935), the instinct of workmanship (Veblen, 1914), and functional autonomy (Allport, 1937).

The Organization of Affect and Aesthetic Experience

But this organization of purpose must be linked with an organization of affect, or emotion. Just what are the satisfactions and frustrations to which the creator responds? How does it feel when the going is good? Or bad? Psychologists interested in emotion chronically focus attention on negative affects: anxiety, depression, fear, guilt, anger, hate. Without denying the power of these darker forces, we must also ask, What are the positive feelings that reward the creative person at work, the presence and prospect of which draw him or her ever back into the unfinished work, and on and on through the long struggle?

The principal aim of this paper is to address one aspect of that question. Specifically, I want to focus attention on aesthetic feelings that arise in a life devoted to science. And here I feel most timid. Whereas there is a wealth of philosophical writing on aesthetics, the aesthetics of science does not follow so easily.

Of course, to the working scientist it is not news that scientific work provokes moments of great feelings of beauty and awe, or other aesthetic experiences: When scientists write or talk about their lives, they often tell about such moments (Keller, 1983; Levi-Montalcini, 1988; Yukawa, 1982). Our task is to get beyond the mere bow of recognition of aesthetics in science toward something more probing and, in the long run, more systematic. For this we will look at a few cases in some detail, especially Charles Darwin and Jean Piaget. But first I want to touch on a few general questions.

Aspects of the Aesthetic Experience in Science

First, we should take cognizance of the point of view reflected when we speak of aesthetic feelings, such as feelings of beauty and awe. Aestheticians are divided on this matter, but for understanding scientific discovery it seems to me that the right place to locate aesthetic experience is as one region within the affective domain, a region where cognition and emotion interact.

Second, it seems to me that the appropriate unit of analysis is not a single emotion or feeling, which might occupy a few seconds, but rather an emotional experience, a structured period of time set off from other such experiences. Metaphorically, we are not speaking of single notes or chords, but rather of phrases, movements, and sonatas.

Third, in this enlarged idea of an emotional experience, it may be that any feeling might participate. Roughness prepares the way for smoothness, calm for thunder, frustration or sadness for joy, banality for astonishment. This opens the question then, whether, if any feeling can participate, what makes an experience an aesthetic one?

Fourth, how does the shape of aesthetic experience change during the life history of the creative person?

Fifth, what are the connections between the organization of affect and the other great organizations—knowledge and purpose—at work in a creative life?

Sixth, to what extent does the creative person have control over the occurrence and course of emotional experiences? Are emotions merely reactions to events in the creative life, or are they also purposeful acts and part of the process?

Seventh, what is the actual function of aesthetic experience in the process of scientific discovery? Psychologists interested in emotion have traditionally differed as to whether its function is primarily expressive, energetic, or directive. My impression is that scientists writing about their own lives often emphasize the directive function, as in statements insisting on the ultimate truth value of beautiful theories, even when those theories seem to be contradicted by the facts currently available. Sometimes, then, the desire to make one’s science more aesthetically satisfying actually guides the direction of the work.

Finally, can science be taught well without adequate attention being given to aesthetic experience? Is the approach that says, “First learn enough, then you’ll appreciate it,” among other things, self-defeating?

Varieties of Aesthetic Experience

When we ask more specifically, “What is aesthetic experience?,” a useful way to begin is by trying to separate characteristics of the experiencing subject from properties of the object (or process, or idea) being contemplated. When we say, “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” we implicitly take cognizance of this distinction, for the statement suggests its negative, that beauty is not in the object. Feelings of beauty and awe are good examples of subjective experience, while attributes of symmetry and complexity are examples of properties of objects.

In addition to properties of objects and experiences of subjects, a third aspect of aesthetic experience in scientific discovery must be the form or medium in which it is represented, both to the experiencing subject and to the world. Images, metaphors, diagrams, narratives, raw feelings and so on, all come to mind as media in which aesthetic experiences take shape. I mention this here for the sake of completeness but will not discuss it further.

I believe it is safe to say that the aesthetic of simplicity, symmetry, and harmony has been the dominant mood among those discussing the aesthetics of science (see, for example, Fearful Symmetry: The Search for Beauty in Modern Physics (A. Zee, 1986), and likewise, C. N. Yang’s (1980) “Beauty and Theoretical Physics”). But an aesthetic of asymmetry, complexity, and diversity has found contemporary voices (see, for example, Freeman Dyson’s chapter, “Manchester and Athens,” in The Aesthetic Dimension of Science (Curtin, 1980), or my own paper, “Darwin’s ‘Tree of Nature’ and Other Images of Wide Scope” in On Aesthetics in Science (Wechsler, 1978)).

In the past fifty years a third aesthetic has come into prominence: the aesthetic of the absurd, the incoherent, the quasi-formless. Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and Pollock’s paintings come to mind as artistic examples; in science, more recently, we have seen the “chaos” movement (Gleick, 1987). Richard Feynman, a Nobel laureate in physics, recently gave voice to a measure of acceptance of this mood:

The theory of quantum electrodynamics describes Nature as absurd from the point of view of common sense. And it agrees fully with experiment. So I hope you can accept Nature as She is—absurd.

I’m going to have fun telling you about this absurdity, because I find it delightful. (Feynman, 1985, p. 10)

Rather than casting the discussion in the framework of a di-or trichotomy of two or three aesthetics, there is another approach that takes fuller account of the diversity of aesthetic experiences. Each person undergoes many forms of aesthetic experience. By attending to the various aspects of this domain, we may be able, eventually, to draw a multidimensional profile of each person and each experience. This approach would also help us to describe developmental changes in the aesthetic experience over the life history.

To give you a sense of this process, consider the following lists of attributes of aesthetic experience, one for the experiencing subject and one for the contemplated object, discussed earlier. These lists are provisional and incomplete, based on a number of conversations, and on autobiographical and other accounts written by scientists. In some cases I have specified both members of a pair of polar opposites and listed them together; I have also listed near-synonyms together. In all cases these are not terms drawn from a thesaurus but are descriptions actually given by people experiencing scientific discovery, and talking or writing about it in a mood of interest in the aesthetic experience:

For the contemplated object

Order, pattern, rhythm, repetition, regularity

Modularity (and non-modularity)

Universality

Law, inevitability

Uniqueness

Simplicity, unity, harmony

Fitness, correspondence, invariance

Balance, equilibrium, symmetry (and broken symmetry)

Complexity, diversity, intricacy

Density, richness of nature

Growth, progress

Reversibility, irreversibility

For the experiencing subject

Awe

Beauty, admiration of nature or science

Surprise, astonishment

Joy, ecstasy, elation

Struggle

Pleasure of contemplation, fascination

Strangeness, familiarity

Expansiveness, flow, growth

With regard to each potential attribute of the aesthetic experience, there probably is no absolute value or intensity that is decisive. It is, rather, change in awareness that evokes the aesthetic experience. In our thinking about these matters, however, room must somehow be made for repeated changes: A symphony does not lose its value or its freshness on the second hearing. M. Csikszentmihalyi and I. Csikszentmihalyi’s (1988) concept of flow—happy, exultant response to challenge—is a sensitive attempt to take account of this need for continuous extension of the self through cycles of strenuous effort, mastery, and accomplishment.

The importance of each attribute to the creator cannot be measured by a frequency count of the number of times he or she mentions it. For example, one cannot imagine D’Arcy Thompson’s great work, On Growth and Form (1917/1942), without imagining the writer as someone in love with pattern; and one cannot appreciate the book without sharing this love. Yet it is written in a rather dry style, and only in the epilogue at the end of the second volume does the author drop the veil: “For the harmony of the world is made manifest in Form and Number, and the heart and soul and all the poetry of Natural Philosophy are embodied in the concept of mathematical beauty.” (Vol. 2, pp. 1096-1097).

I turn now to the examination in some detail of one scientist’s aesthetic experience.

Charles Darwin’s Aesthetic Fate

My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts, but why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive.…The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature. (C. Darwin, 1958, p. 139)

Charles Darwin’s well known confession of the atrophy of his aesthetic sensibilities should be taken seriously, but in context To do this we must look at the trajectory of Darwin’s aesthetic development. He wrote his autobiography between the ages of 67 and 73. In it, he describes his earlier interest in various arts: music, poetry, fiction, drama, painting. From this document, from his notebooks, and from his published writings, it has been possible to reconstruct a fairly full account of Darwin’s aesthetic tastes and development in the arts. (For a recent and probing effort, see Beer, 1983.) It appears that Darwin had a long and very full period of interest in the arts, fluctuating in intensity from moderate to very strong. Even in his later years he retained a love of fiction, especially novels with happy endings, as might befit an apostle of evolutionary progress.

More to the point, perhaps, is an examination of Darwin’s s...