Economic analysis is concerned with the understanding of how the economic system works and what the effects of various kinds of social, economic, and policy changes are likely to be. Every citizen has ideas of his own on these matters; what distinguishes the economist is the consistent application of a body of logical principles and methods of empirical verification developed and tested by the work of generations of economic scholars. The development of scientific economics has necessarily required heavy reliance on the main principle of all scientific enquiry: the use of logical abstraction to reduce a problem to its essentials and permit concentration on those essentials to be untrammelled by peripheral detail.

For most of its contemporary history, economics has performed the necessary abstraction by assuming that it is a legitimate approximation to isolate a single market from, the complex network of tnarkets, ignoring ‘feedbacks’ from, that market to other markets and thence back into the market under analysis, and analysing the market under study in terms of the familiar ‘partial equilibrium’ concepts of demand and supply. These concepts can take one a very long way towards understanding of how the economicsystem works—but not the whole way; and it is often difficult to determine the borderline between conditions under which partial equilibrium analysis contains the usable predominance of truth, and conditions under which the ‘feedbacks’ dominate the results. Consequently, economists have increasingly come to the belief that a ‘general equilibrium’ analysis—i.e. an analysis which concerns itself with the equilibrium of the whole system, and not of just a sub-sector of it—is necessary both for scientific dependability and for checking the reliability of the results of partial equilibrium analysis.

The purpose of this book is to develop from its foundations the simplest kind of general equilibrium analysis, the so-called ‘two-by-two-by-two’ model of general equilibrium (two goods produced, two factors required to produce each good, two individuals with different shares in. the ownership of the economy’s factors and therefore with different income prospects); and to apply that model to a number of problems of general interest in such fields as public finance and tax incidence, the distribution of income among persons, and the effects of international trade and of commercial, policy measures on economic welfare and income distribution. Our main purpose, however, is not to provide ceremonially adequate answers to set questions, but to show the reader how a fairly simple set of technical economic tools, once mastered, can be applied to an unexpectedly wide range of economic problems with fruitful results.

I. Method of Analysis

There is a generally accepted distinction between two methods of economic analysis: the ‘static’ and the ‘dynamic’. The central concept in static analysis is that of equilibrium, defined as the position which if attained will be maintained under ceteris paribus conditions (no change in the ‘givens’ of the system). There are two analytically distinguishable components of static analysis ; that of statics proper, which is exclusively concerned with the position of equilibrium under ceteris paribus conditions, and that of comparative statics where attention focuses on the comparison of two or more different equilibrium positions. Comparative statics involves studying the consequences for the static equilibrium of the system of changing one or more of the ‘givens’ of strict static analysis. It is a method of studying dynamic change in the system, which proceeds by reducing dynamic change to once-over shifts in the ‘givens’. Dynamic analysis, on. the other hand, is concerned on the one hand with the stability of pure static equilibrium—i.e. if there were a chance departure from static equilibrium, are there forces that would drive the system over time back to the initial equilibrium or would it instead, be driven to some alternative equilibrium position?—and on the other hand with the time-path of adjustment of the system to a lasting change in the ‘givens’ of the system—will, the system approach the new static equilibrium in a steady asymptotic fashion, or with oscillations, and if there are oscillations will they fade out gradually over time or will they increase in amplitude so that the economy never actually reaches a new stationary equilibrium? A stillmore ambitious dynamic economics, developed in the past quarter century or so, assumes that the ‘givens’ (e.g. population size, available technology) change at a steady rate over time, and is concerned with whether the economy will settle down to a steady-state growth path determined by the exogenously-given rate of change of the variables taken as given in pure and comparative static analysis.

The two-by-two-by-two model presented in this book is in the field of pure and comparative statics. However, there is an initial problem about static equilibrium which overlaps into the field of economic dynamics. This is the question of whether the static equilibrium of the system is unique, or whether multiple equilibria are possible. The overlap with dynamics arises from the consideration that if the equilibrium is not unique, one has to distinguish between ‘stable’ and ‘unstable’ equilibria, i.e. between equilibria that would be self-sustaining against random shocks and equilibria that would be destroyed, and replaced by another equilibrium, in case of disturbance by any random shock. In order to analyse this question, one needs a theoretical specification of how the system adjusts to disequilibrium, i.e. a theory of the dynamic motion of the system when it is disturbed. The simplest and most generally accepted theory, though by no means the only possible one, is the ‘Walrasian’ or ‘Hicksian’ theory that if there is excess demand for a commodity at a particular price competition will tend to drive that price upwards, and vice versa if there is excess supply at a particular price. This permits one to say that an equilibrium position will be ‘stable’ if a small fall in price will produce an excess of quantity demanded over quantity supplied and vice versa for a small increase in price; and conversely an equilibrium will be ‘unstable’ if a small fall in price produces an excess of quantity supplied over quantity demanded and vice versa for a small increase in price. By extension, a small change in, the ‘givens’ of the system will produce a predictable change in the characteristics of equilibrium of the system if that equilibrium is ‘stable’ ; but if the initial equilibrium is ‘unstable’, one cannot tell what the effects of a disturbance will be.

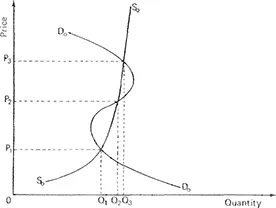

The point may be illustrated in terms of the familiar demand and supply curve apparatus. If the demand curve is always downward-sloping to the right, and the supply curve always upward-sloping to the right, the two curves can intersect only once, and in a stable equilibrium position; and any change in demand or supply conditions will produce predictable changes in the equilibrium price and the quantity supplied and demanded. But there is the possibility that demand or supply curves are not ‘well-behaved’, and that consequently they intersect more than, once, producing a case of ‘multiple equilibrium’.

The standard case of this possibility is illustrated in Figure 1.1, where as price falls over a certain range quantity demanded also falls. The common explanation of this possibility involves the so-called ‘Giffen good’, i.e. an inferior good in the sense that as people’s real income or purchasing power rises they will consume less of the good, but with the added condition that the ‘income effect’ on real income or purchasing power of a fall in the price of the good—which leads people to demand less of the inferior good—is stronger than the ‘substitution effect’ of the reduction in the price of the good relative to other goods—which should lead people to substitute this now-cheaper good for other goods. The ‘Giffen good’ possibility is rather far-fetched, since with both high prices and negligible consumption and large consumption at very low prices the income effect cannot be large enough to outweigh the substitution effect (a point illustrated by the slope of the demand curve in Figure 1.1). However, as we shall show later, in a genera! equilibrium context a change in the price of a commodity will involve a change in the distribution of income among factor owners, and differences in preferences among the latter may result in an association of a price reduction with a reduction in quantity demanded even though the good in question is not inferior in anyone’s consumption. (The reader should note in passing that if the suppliers of a good consume some of it themselves, a rise in its price could lead them to produce more of it but to supply less of it to the market, again creating the possibility of more than one intersection of the demand and supply curves. This possibility figured largely in the accepted theory of development planning in the 1950s, according to which taxation of farm production would increase the marketed supply of farm products ; but the weight of the empirical evidence is that marketed farm production is an increasing function of the market price of the product.)

In Figure 1.1, D0D0 is the demand curve and S0S0 the supply curve. Three intersections of the curves are depicted, with equilibrium prices, P1, P2 and P3, and equilibrium quantities Q1, Q2, Q3. So long as we can assume that at a high enough price nothing will be demanded, and that at a low enough price nothingwill be supplied, there must be an odd number (three, five, seven, etc.) of intersections of the two curves. Furthermore, as is evident from the diagram, the odd-numbered intersections (first, third, fifth, etc.) will be stable equilibria on the definition adopted above, while the even-numbered intersections (second, fourth, etc.) willbe unstable equilibria. In other words, an unstable equilibrium point willalways be bordered onboth sides by stable equilibrium points. One might therefore assume that only stable equilibrium points willever be observed in reality—specifically, we would never observe the combination P2Q2. However, the possibility exists that a random disturbance of equilibrium could move the system from the equilibrium position P1Q1 to the equilibrium position P3Q3 or vice versa.

This possibility becomes still more awkward if we move from pure statics to comparative statics. Consider, say, a shift of the demand curve due to a change in the givens of the system. Suppose P3 is our initial equilibrium point, and for some reason the demand curve shifts leftwards. For successive small changes, equilibrium price and quantity will both fall by small amounts. But eventually the demand curve will become tangent to the supply curve, we will have an unstable instead of a stable equilibrium, and the system will have to make a discontinuous jump from the P2P3 range down to a price-quantity combination below P1Q1. (The tangency case can be thought of as still involving three equilibrium points, of which two are identical with respect to price-quantity combination but one is stable for upwards price movements and the other unstable for downwards price movements.)

The possibility of multiple equilibria, including unstable equilibrium positions, is clearly awkward for economic analysis. If the economy may make discontinuous ‘jumps’ from one equilibrium neighbourhood to another, instead of sticking to a unique equilibrium position determined by the ‘givens’ of the system and moving to a uniquely-determined new equilibrium when the ‘givens’ change, nothing can be said reliably about either the characteristics of equilibrium or the effects of changes in the ‘givens’. Unfortunately, it is not possible to rule out the possibility of multiple equilibrium on a priori grounds; one simply has to assume it away, in order to get on with the business of analysis. Fortunately, though, the conditions required to make multiple equilibrium possible can be shown to be empirically implausible—as with the ‘Giffen good’ and ‘income redistribution’ cases discussed above—so that analysis can. safely be conducted on the assumption of a unique stable equilibrium position.

This assumption has a great simplifying virtue. If we can assume that equilibrium is stable, and specifically that an excess of quantity demanded over quantity supplied at a given price necessarily requires an increase in that price to restore equilibrium, we can conduct our qualitative comparative-statics analysis of the effects of changes in the ‘givens’ of the system by asking what effects these changes would produce on the net balance of quantities demanded and supplied at the initial equilibrium prices. If the net effect is an excess demand in a particular market, price in that market must rise, and vice versa. And since the prices of goods and of factors are related, we can use results for the goods market to predict results for the factor market, and vice versa.

This brings us to an important general point about the model developed in this book, which is that its main interest lies in the connection between commodity prices and factor prices, i.e. incomes of factor owners. In a two-commodity model, there can be only one relative commodity price ; and, by Walras’s law, if that price clears one commodity market (establishes equilibrium in that market) it must simultaneously clear the other. Partial equilibrium analysis conducted in terms of demand curves and supply curves is therefore capable, if used with some sophistication, of analysing equilibrium in the commodity markets. The virtue of general equilibrium analysis in the model under consideration is that it links commodity prices, factor prices, and income distribution together in the determination of the general equilibrium of commodity and factor prices.