![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Inherent Selectivity of the Council's Roles

The UN Charter system provides a much more robust framework for collective action than any previous attempt at global order. It differs hugely from all its predecessors, including the Concert of Europe in the nineteenth century and the League of Nations in the interwar years. As a result, it has often been asserted that the Charter represents a scheme for collective secu-rity.1 However, we question whether the Charter, even in theory, provides the basis for such a system, at least if defined in the classical sense.

The term ‘collective security’, in its classical sense, refers to a system, regional or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and agrees to join in a collective response to threats to, and breaches of, the peace.2 This is the meaning followed here. The assumption is that the threats to be addressed may arise from one or more states within the system. Collective security as defined here is distinct from, and more ambitious than, systems of alliance security or collective defence, in which groups of states ally with each other, principally against possible external threats.

There is a long history of the armed forces of many different states being used in a common cause. There is also a distinguished pedigree of leaders who have sought to establish a system of collective security, viewing it as superior to the balance of power as a basis for international order. Cardinal Richelieu of France proposed such a scheme in 1629, and his ideas were partially reflected in the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.3 Sadly, the history of proposals for collective security is a long record of failure.4

Selectivity in the Charter

While the UN Charter has collective-security elements, it can better be read as providing a framework for selectivity on the part of the Security Council. In the Charter scheme, the Security Council has primary, but not exclusive, responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security.5 The Council is tasked with determining on behalf of the UN membership whether particular events or activities constitute a threat to international peace and security, and for authorising the use of sanctions and force in a wide range of situations. As Article 24(1) puts it:

In order to ensure prompt and effective action by the United Nations, its Members confer on the Security Council primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security, and agree that in carrying out its duties under this responsibility the Security Council acts on their behalf.

Remarkably, Article 25 of the Charter, like some articles in Chapter VII, specifies that UN members accept an obligation to do the Security Council's bidding: it is here that the Charter comes closest to a vision of collective security. However, there are also many Charter provisions suggesting a more selective role for the Security Council. Six are outlined below.

The veto

The power of veto, conferred on the P5 by the Charter, is by no means the only factor providing for selectivity on the part of the Security Council, but it is certainly the best known and the most controversial. Charter Article 27, on voting, gives each of the P5 members a veto power. As the article delicately puts it, Council decisions on matters that are not procedural ‘shall be made by an affirmative vote of nine members including the concurring votes of the permanent members’.6 When the great powers discussed the creation of a new world organisation at Dumbarton Oaks in 1944, they agreed on the veto provision so as to guarantee that no military action could be authorised that they did not endorse. Smaller states accepted this to ensure the participation of the great powers in the organisation. The veto power of the P5 has been the subject of controversy throughout the history of the UN.

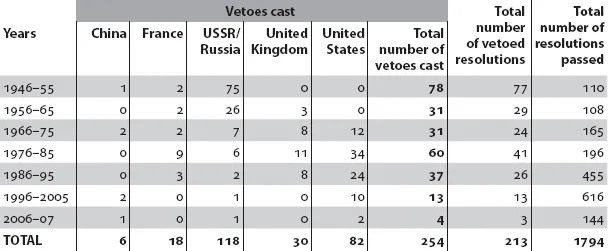

Table 1 shows that the veto has been used extensively since 1945, especially in the first and fourth decades of the UN's existence, and that its use declined dramatically following the end of the Cold War. Particularly during the Cold War, but also to a lesser extent after it, the use of the veto prevented the Council from taking action on issues in which one or more of the P5 wanted to limit international involvement. Even when the veto is not actually used, it still casts a shadow. In the case of Darfur, a Chinese veto threat for a long time limited the measures authorised by the Security Council, while in the case of Kosovo, the threat of a Russian veto ensured that the Council was not able to resolve the question of the territory's political and legal status.

Table 1: Vetoes cast, vetoed resolutions and resolutions passed in the UN Security Council, 1946–2007

Sources: UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, United Nations

One attempt to get around the immobilism induced by the P5 veto was the ‘Uniting for Peace’ resolution passed by the General Assembly in November 1950, which made provision for the General Assembly to act in certain crises or wars when a veto prevented Council action.7 It came about as a US-led response to the possibility that the Soviet Union might veto the continuation of UN authorisation of the US-led forces in the Korean War. The resolution provides that the General Assembly can call an emergency special session to discuss a crisis, and make recommendations. Since the Korean War, the ‘Uniting for Peace’ procedure has been invoked 11 times: seven times by the Security Council, and four times by the General Assembly.8 The resolution has been employed to request the creation of a UN peacekeeping mission (UNEF, during the Suez crisis in 1956) and to confirm the mandate of a mission (ONUC in the Congo in 1960). It has been used to condemn armed interventions (in Suez and Hungary in 1956, Lebanon and Jordan in 1958, Afghanistan in 1980 and the Golan Heights in 1982) and to call for ceasefires (in the Suez crisis and the 1971 India–Pakistan War). It has been invoked to promote decolonisation in Namibia (1981). It has been used, by both the Security Council and the General Assembly, to condemn some of Israel's policies in the Occupied Territories (on various occasions since 1980, most recently in April 2007), and to ask for an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the legality of the construction of a wall by Israel in the West Bank.9 Significant as this range of activities under the ‘Uniting for Peace’ procedure is, it does not change the fact that the Security Council veto continues to be the most visible and serious of the many factors that inhibit UN action.

The Council's discretion

Selectivity is inherent in the provisions of Chapter VI (Arts 33–8) of the Charter, which addresses the peaceful settlement of disputes, and Chapter VII (Arts 39–51), which sets out the Council's powers to act in the face of threats to international peace and security. In contrast to the ambiguous language of the League of Nations Covenant, the Charter seeks to identify a single agent – namely the Council – as holding the power to interpret the implications of disputes, conflicts and crises. In its role as maintainer of international peace and security, the Council is empowered by Article 39 of the Charter ‘to determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression’ and to ‘make recommendations, or decide what measures shall be taken … to maintain or restore international peace and security’. Crucially, the Charter sets no limits on the discretion of the Council to make a determination under Article 39.

This right to act selectively was deliberately maintained during the drafting of the Charter: proposals to include detailed definitions of threats to international peace and security, in order to constrain the Council, were defeated. The Council is therefore not tied to any particular legal notion, such as aggression, in making its determinations. Proposals to define and apply terms such as aggression, and efforts to make Council action obligatory in particular circumstances, were driven by small states’ concerns that the Council would fail to act.10 By contrast, since the end of the Cold War, the Council has determined with increased frequency that even events internal to a single state threaten international peace and secu-rity.11 Indeed, some states are now uneasy with the growing scope of the Council's actions. While in the past the Council made most of its determinations in relation to specific crises and threats, more recently it has done so in relation to general threats, for example in its resolutions in 2001 and 2004 on terrorist acts and on nuclear non-proliferation.12

The breadth of the Council's discretion to decide what triggers its powers under Chapters VI and VII is mirrored by the breadth of those powers themselves. Unlike that of member states, the Council's right to use force is not limited to situations of self-defence. If it wished to initiate preventive military action in order to avert a threat to international peace and security, it could do so. Chapter VII gives the Security Council the right to use ‘measures not involving the use of force’ (Art. 41), such as economic sanctions or the severance of diplomatic relations, to maintain international peace and security; it also provides the right to use force ‘should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate’.13 Thus there is no necessity for the Council to try sanctions before resorting to force: it is up to the Council to select the appropriate instrument.

Selective implementation of decisions

The Charter also recognises that the implementation by states of Security Council decisions might sometimes be selective and, for example, be undertaken by a limited number of states. Article 48(1), by specifying that some actions may be taken by groups of states rather than the membership as a whole, provides a basis for the Council's later practice: ‘The action required to carry out the decisions of the Security Council for the maintenance of international peace and security shall be taken by all the Members of the United Nations or by some of them, as the Security Council may determine.’

Inherent right of self-defence

This understanding of the Security Council as the lynchpin of a selective, rather than collective, security system is also underlined by the provisions of Article 51 of the Charter. These make it clear that states have an already existing right of self-defence, which is simply recognised (and not conferred) by the Charter. ‘Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security.’ Importantly, while the article recognises the right of the Council to take action in such cases, there is no obligation on it to do so. There is no presumption in the Charter that the Security Council offers a complete alternative security system replacing that of states or groups of states.

Regional arrangements

The Charter recognises that the Security Council cannot tackle all problems of peace and security alone, but will have to be selective and at times act together with regional security arrangements. The key issue of how the UN and regional security arrangements might coexist and even reinforce each other was discussed extensively in the Dumbarton Oaks negotiations, partly in recognition of the fact that not every international security problem could be addressed at the global level. Article 52(1) of the Charter states:

Nothing in the present Charter precludes the existence of regional arrangements or agencies for dealing with such matters relating to the maintenance of international peace and security as are appropriate for regional action, provided that such arrangements or agencies and their activities are consistent with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations.

Regarding the delicate question of how the Council and regional arrangements should relate to each other, Chapter VIII of the Charter (Articles 52–4) clearly emphasises the primacy of the Council. In particular, it specifies the need for it to authorise any use of force by regional security arrangements, and it imposes an obligation on regional bodies to keep the Council informed of ‘activities undertaken or in contemplation’.14 It is asking a lot of states, and of the Council, to expect these precepts to be followed in all cases, but if the Charter had failed to make such requirements, it would have undermined the primacy of the Council even before it came into existence. In practice, the requirement that the enforcement actions of regional bodies be authorised by the Security Council was little heeded during the Cold War, as there was never much chance of securing both US and Soviet consent for any particular military action by a regional or indeed any other body; but since 1991, many Council resolutions have referred to the military actions of regional organisations.15

Relations between the UN and NATO in particular have been complex in this regard. Throughout the Cold War, NATO sought to emphasise its role as a collective defence alliance, rather than a regional body, within the meaning of the UN Charter, so as to make clear that it was not bound by the obligations to keep the Council informed of planned activities and to seek Council authorisation for the use of force, which would have subjected it to the threat of a Soviet veto in the Council. Since the end of the Cold War, however, NATO has regularly acted as a regional organisation on behalf of the Security Council, in particular in the former Yugoslavia.

The relationship between the UN and regional bodies has proved to be more varied than was envisaged in 1945. Increasingly, regional bodies have acted with Council approval outside their own region, for example NATO in Afghanistan since January 2002 and the EU in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in 2006. Furthermore, Council resolutions have given retrospective approval to certain actions of regional bodies, for example the endorsement of the intervention in Liberia by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in 1990.

At times, the Council has also authorised regional bodies to operate alongside a UN peacekeeping operation: a prime example of this is in Kosovo, where NATO-led KFOR troops have been responsible for maintaining peace and security, while the UN Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), although it is formally classified as a UN peacekeeping operation, has been mainly concerned with its responsibilities for policing, institution-building and governance. In Darfur, the Council has gone one step further and established for the first time a ‘hybrid’ peacekeeping force (UNAMID) under the joint control of the UN and a regional body, in this case the African Union.

There are solid reasons for the increased reliance on regional bodies to address security problems. Some regional bodies and alliances have, or plan to have, forces available and a capacity to act promptly that the UN conspicuously lacks. The ability of certain regional forces to operate outside as well as within their own region is particularly striking. Moreover, the post-1945 tendency for civil wars to be among the principal problems of international relations poses a problem for the Security Council. It is not obvious that there is a strong global interest in addressing every civil war, nor that the UN has the appropriate resources at its disposal to do so. There has to be selectivity in determining which conflicts to address at a global level, regionally, or in combination.

The ‘enemy states’ provisions

Finally, Articles 53 and 107 left each of the wartime Allies a free hand to handle their relations with Second World War enemy states outside the Charter framework. These articles were a significant concession to unilateralism in the conduct of the post-war occupations, but they have been a dead letter for many years, and the World Summit of September 2005 proposed the deletion from the Charter of references to ‘enemy states’.16

Not a collective security system

Although the Charter is not a blueprint for a general system of classically defined collective security, it may be compatible with a looser definition of collective security. In the 1990s, US diplomat James Goodby suggested that classical definitions had been ‘too narrowly constructed to be a practical guide to policy analysis, especially when considering the use of military force’. He therefore proposed a definition of collective security as ‘a policy that commits governments to develop and enforce broadly accepted international rules and to seek to do so through collective action legitimized by repres...