THE FIRST SERIES

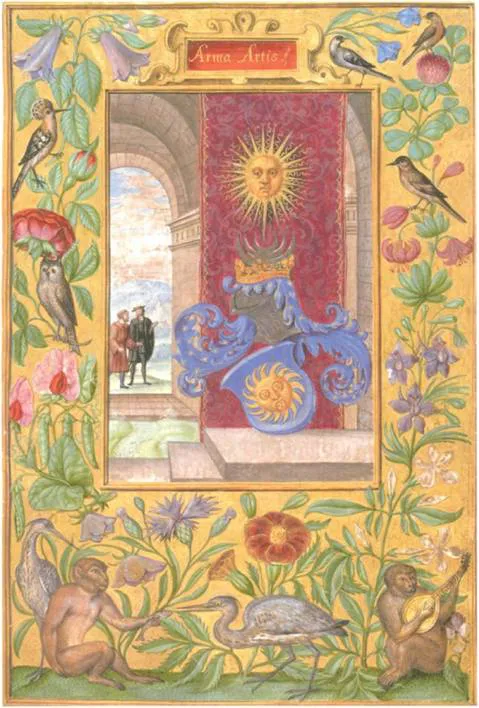

Plate I–1

A Sick Sun and a Healthy Sun1

THE SYMBOLISM OF THE first painting of the Splendor Solis, which is the frontispiece of the illuminated manuscript, informs us that this work does not concern itself with methods for the practical, concrete transformation of base metals into gold. For the author of the Splendor Solis, alchemy was a practice for the healing and transformation of the human soul.

The world of this beautiful painting is full of the unexpected and the paradoxical, challenging our ordinary assumptions: a coat-of-arms proclaims weakness and disintegration, animals play musical instruments and show generosity to other species, and a two-dimensional image on a banner becomes three-dimensional, swirling out into the scene. As we look at it carefully, we may begin to feel unsettled.

The large, golden trompe-l’oeil frame conveys the great value of the painting within. On the upper part of the frame, the words, ‘Arma Artis’ are inscribed in gold letters on a crimson background. The Arms of the Art,’ presumably tells us that the coat-of-arms in the banner below represents ‘the art’ of alchemy

Within the painting, we see two men engaged in conversation, standing upon verdant ground just beyond a high archway. Presumably, one of the men is the alchemist, and the other is his adept or student: alchemy, like analysis, involved relationship and discourse. As he speaks, the man dressed in black gestures toward the right with his left hand, while the other man, dressed in red, faces in that direction and looks intently, as if anticipating something or seeing something for the first time. They are separated from the viewer by a waterway, in which rapidly flowing, turbulent water has risen nearly to the level of the pavement. Yet the two men do not seem alarmed.

Behind them lies a landscape with a town or fortress on a steep hillside in the distance, with a mountain still further away. They are standing just outside a gate to the city, implying that alchemy requires one to step outside the familiar structure of one’s life and set out on a journey Their relationship suggests that, although this journey will be solitary in the sense of being unique to the individual, it is undertaken with the counsel and companionship of one who has returned from his own journey

This reminds us that the still-popular ideal of the solitary hero’s quest of self discovery—like the Greek Ulysses or the Neoplatonic solitary journey to the One—was challenged by Dante as long ago as the fourteenth century. In The Inferno, the poet fails in his attempt to climb up a mountain to reach the entrance to the underworld. He begins anew, this time assisted by Virgil:

…my guide climbed up again And drew me up to pursue our lonely course. Without the hand the foot could not go on.2

The central area of the painting is dominated by a crimson banner. At first glance, the design appears to be a stereotypical coat-of-arms, but when we observe the lower part closely, we realize that it is a coat-of-arms in a process of falling apart. The design on the upper portion suggests the martial regalia of a king, with the helmet embellished by several waving plumes and a crest composed of three silvery crescent moons. Above the crown, brilliant against the darkened background, shines a golden sun with human features and a steady gaze. Its rays, alternating straight and sinuous, spread out in all directions. The lowest of its downward-pointing rays penetrates the concavity of the topmost crescent moon. The blue star-studded fabric attached to the helmet whirls out past the banner, as if it is transforming from two dimensions into three. Below the helmet, a shield rests on the pavement, tilting toward the viewer’s left, so that the golden sun depicted upon it is askew. Moreover, the lower sun’s human features are as horrifying as the upper sun’s features are benign. The face of the lower sun is pock-marked and, from each eye and extended tongue, a tiny, demonic face peers forth. Instead of straight rays, the rays emanating from this sun are like hooks that bend back upon themselves.

The cultural symbols found in the illuminated paintings of the Splendor Solis reflect a radical change of attitude toward the ideals of medieval chivalry that was taking place in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. The knight, who had once seemed invincible in his heavy metal armor, was seen as weighed down and awkward:

Knighthood, a pivotal medieval institution, was dying. At a time when its ceremonies had finally reached their fullest development, chivalry was obsolescent and would soon be obsolete. The knightly way of life was no longer practical. Chain mail had been replaced by plate, which, though more effective, was also much heavier; horses which were capable of carrying that much weight were hard to come by, and their expense, added to that of the costly new mail, was almost prohibitive. Worse still, the mounted knight no longer dominated the battlefield; he could be outmaneuvered and unhorsed by English bowmen, Genoese crossbowmen, and pikemen led by lightly armed men-at-arms, or sergeants.3

In the humanistic light of the Renaissance, the knight and his chivalric order seemed patronizing and, as Cervantes represented them, even ridiculous.

In this alchemical coat-of-arms, primordial elements are replacing the old cultural images. A king in his battle-armor is the incarnation of the principle of dominion through force, but here we see that his costume is empty, collapsed. Yet the upper sun shines steadfastly, its prominent lower ray pointing toward the three crescent moons below. To understand the symbolism here, it is important to remember that in European alchemy, the moon was usually associated with the Feminine Principle and the sun with the Masculine Principle. So this configuration suggests that help is needed from the restorative power of the feminine, a theme we shall encounter repeatedly in this series. With regard to the presence of three crescent moons, a conjecture by Marie-Louise von Franz points to an underlying psychological theme: Threefold rhythms are most probably connected with processes in space and time or with their realization in consciousness.’4

Finally, we should remark on the position of the viewer in relation to the banner. We face it but cannot see how it is held up, and we are on the inside of the city looking out. This banner does not declare a worldly power backed by force-of-arms, promising protection for the viewer from danger without; rather, the viewer is faced with a failure and dissolution of an order that had once seemed impregnable.

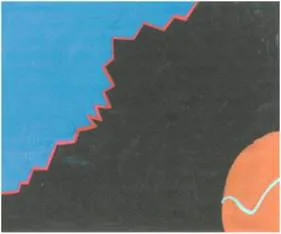

FIGURE 9 ‘Heaven and Earth are Far Apart’ (Painting by a woman in analysis)

This scene is analogous to the beginning of an analytic encounter between analyst and patient.5 The analysand might have been trying very hard to sustain a heroic over achievement, represented by the knight’s helmet. The patient’s psyche is divided, as represented by the healthy (upper) sun and the (lower) sick sun. The sick sun is isolated, distorted, cut off from relationship, and morbidly subjective, suggesting self-doubt and self-loathing—a true description of a neurosis. The person so afflicted also has a healthy side, which may be projected onto the analyst as healer and carrier of consciousness during the course of work on the less healthy part

An example of this painfully divided state of being is shown in Figure 9. A woman in analysis made this painting several years into the work, when her personality was in a profound state of upheaval. Her heroic defenses had failed her, and she was often in despair about how she could live her life. The sun is barely visible in the upper left-hand corner, and the earth is barren except for a snaking river. A jagged red line separates the darkness surrounding the earth from the blue sky above. This painting shows the way an inner state is often represented as something in the natural world, a felt correspondence of the personal (microcosm) and the outer world (macrocosm), which will be discussed further in relation to Plate I-9.

Thus, from a psychological point of view, the alchemical coat-of-arms might be viewed as the configuration of a certain schizoid condition that threatens to become paranoid and overshadow the personality It might also refer to any defense which once served the individual (or was necessary for survival) but has outlasted its usefulness.

The defense may be represented in dreams by attire, such as a uniform or helmet, or by an animal or human figure. For example, a woman in her twenties came into analysis in a depressed, withdrawn, and fearful state. This state contrasted with her usually enthusiastic and upbeat persona (represented in her dreams as a cheerleader), academic achievements, and tirelessness. Some months into therapy she dreamt that,

I was bathing a tiny turtle in a bowl of water, and the turtle’s shell came off. I attempted gently to support it with my hand because its interior skeleton was too weak to provide adequate support for it to keep its head above water. A woman of my acquaintance, who is demanding and insensitive, was with me, and she became angry at the turtle for slouching. I was afraid that she would cause it some permanent damage. I also saw that it would not be possible to replace the shell, because it had been damaged when it came off.

The shell of the turtle represents a defense against emotional lances and blows. The patient identified her true self as vulnerable, like the shell-less turtle, unable to support herself from within. She felt that the acquaintance in the dream represented a judgmental and self-scrutinizing part of herself who demanded performance and efficiency, and she was surprised that her dream ego was so caring and protective toward the turtle. She related this new sensitivity to the care of the analyst who had not judged her harshly for her difficulties, but we can also view it as coming from a deeper, wiser part of herself.

This dream was a moving image of a fundamental problem that the patient and the analyst would be addressing. In practical terms, the analyst used the image of the shell-less turtle to remind herself of the patient’s underlying vulnerability and anxiety. This was especially helpful when the patient was in a hypomanic ‘cheerleader’ state. Those times were painful to the analyst because the patient’s defense precluded authentic empathic contact. The image from the patient’s dream helped the analyst to hold the patient’s more vulnerable parts and to ask herself what might have happened between them or in the patient’s s life that had caused the shell to be put back in place during their session. This is an example of the way symbols in dreams are more than a reductive or a purely relational aspect of the transference-countertransference. They may symbolize the problem in a much broader and deeper way that will give both the therapist and the patient support and holding while the delicate process unfolds.

Understandably, the patient was reluctant to risk the uncovering process, nor was she ready to acknowledge consciously her transference fear of the analyst’s judgments. Much careful work lay ahead to pave the way for those feelings to be openly acknowledged. (There is additional alchemical symbolism in this dream, including the solutio of the bath.6 As throughout the book, we will not present an extended interpretation of dreams or clinical process; the focus will be on the symbolic connection to the Splendor Solis image under discussion.)

Another woman in analysis reflected on the defenses that had cut her off from herself, already in place by adolescence:

Patient: …which is where I was when I was twelve, like the way he was treating me last night.

Analyst: It took you back to that emotional field.

Patient: Where there is a heavy coat of armor. (long silence)…

Analyst: Can you speak as an adult about the twelve-year-old?

Patient: Yes, I’d say he doesn’t get it.

Analyst: What doesn’t he get?

Patient: The fact that she can’t express her true self to him because she hasn’t the language. That his demands for her performance harden her, so that all he or anyone else will know is the exterior like a shell. It may be a beautiful shell like a turtle but he will never know the inside of her. (silence) Or it may be a hideous shell, but again he won’t know what’s inside. He won’t know that her core is being twisted in unspeakable ways, and even more damaged by not acknowledging what we—she and I—plainly see. I guess I would also point out that although her mind has appeared functionally adequate that we know nothing about her underbelly.

This hidden thing that we know nothing about is the prima materia. But what could motivate a person to face something unknown yet attended with emotions of horror and shame? The symbolism of the coat-of-arms may help us here: the steady and balanced upper sun can be seen to represent some larger and wiser aspect of the patient’s personality not necessarily conscious, which helps to balance paranoid anxieties with hope for healing. It may also represent the streng...