eBook - ePub

Art in the Roman Empire

Michael Grant

This is a test

Share book

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Art in the Roman Empire

Michael Grant

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Michael Grant's huge following Popular subject with the general reader Short, illustrated book with lavish jacket

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Art in the Roman Empire an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Art in the Roman Empire by Michael Grant in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia antica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SCULPTURE

1

IMPERIAL PORTRAITS

As early as the third millennium BC, Egypt and the cities on the Persian Gulf had developed effective methods of portrait sculpture. Much later on, during the last centuries BC, a number of different phenomena in the Greco-Roman world contributed to the revival and further evolution of this art. The Greeks of the epochs of Alexander III the Great (d. 323 BC) and his successors, the Hellenistic monarchs, had a liking for human documents of a biographical or autobiographical character. This tendency was stimulated by a fashion for philosophical reflection and self-analysis, as well as by the enhancement of hero-worship, and the growing interest in personalities which such trends encouraged.

In other words, the Hellenistic epoch was an age of enhanced concern for the individual. In contrast to the Greek sculptors of classical times, who had endeavoured to present a human being as a focus of generalization, the artists who came after them sought to emphasize and stress the unique characteristics of whatever man or woman they were depicting. Like the biographers who were their contemporaries, these Hellenistic artists meticulously took note of contrasting and ambiguous characteristics in the personages whom they depicted, and of the coexistence in them of factors that seemed to be contradictory.

Their concentration on such aspects was stimulated by a study which was very much à la mode in these Hellenistic years – physiognomy. Originating as a branch of Greek medicine, ascribed to the fifth-century physician Hippocrates, this science, or pseudo-science, had come into favour during the century which followed. One of its subdivisions was zoological, pointing out the analogies between human beings and animals, and another was ethnic, seeking to define the distinctive peculiarities of races or peoples by consideration of their physical differences. Students of physiognomy also took note of revelations of personal character through facial expressions (a critic of this technique pointed out that if you applied it to Socrates he turned out to be stupid and keen on women!). The best-known authority on physiognomy was Antonius Polemo (c. AD 88–144), a popular philosopher or sophist from Laodicea (Pamukkale) in Phrygia (Asia Minor), whose writings were destined, subsequently, to exercise an influence on Islamic writers.

These were the elements which – augmented by the survival of a number of much earlier Egyptian busts – created a new efflorescence of portrait sculpture in the Hellenistic world. True, by way of contrast to the abundance of heads and portrait-statues of later Roman epochs that have come down to us, relatively few from the last centuries BC are now extant. Yet certain Hellenistic artists, such as the creator of the portrait of the Indo-Greek monarch Euthydemus I Theos (c. 220 BC), or the originator of studies of an old and brutalized fisherman of which later versions are extant, or the portrayer of King Mithridates VI of Pontus (d. 63 BC) (in a more idealized form) upon coins, can still be seen – and are so excellent that it was hard for their successors to do any better.1

That was not, however, for want of trying, and the last century BC was a period when the renewed and increased impact of Greek sculpture upon the family traditions of eminent Romans brought remarkable developments in portraiture into existence. They took place because of the massive financial incentives which those Romans offered: they were among the most notable and lucrative patrons of the arts that the world has ever produced. Those portions of Latin literature which still survive frequently allude to the decoration of the mansions and villas of distinguished Romans with Greek works of art – including portrait-busts.

And these houses contained numerous copies as well: for Romans who could afford to do so commissioned copies of these Greek artistic productions of all periods, from the sixth century BC onwards – thus preserving for posterity, at least in their main features, numerous masterpieces made by the Greeks. It must be admitted that these copies in Roman mansions did not invariably achieve perfection. For their creators were not always fully aware of the methods that a Greek artist had employed, or of the full nature of his achievement. Such ancient art-criticism as has come down to us too often fails to display a great deal of insight. Let us consider, for example, Pliny the Elder, who is probably one of the best of the critics, although both his knowledge and his taste are faulty. The greatest sculptor, according to him, had been Lysippus of Sicyon, the selected portrayer of Alexander III the Great. But Pliny was of the opinion that all paintings and bronzework were excelled by the later Laocoon Group, that unrestrained, tormentedly baroque creation that was one of the last important Hellenistic originals, the work of Rhodian sculptors of the second century BC (although it is possible that the version which we possess is a copy from the first century AD).2

Most leading Romans possessed much less knowledge of art than Pliny, yet they ‘knew what they liked’, and, by offering good money, set a vast and demanding task to the Greek and other sculptors of the last century BC onwards. What these potential employers wanted most of all was portraits; and something will be said about the artistic successes that resulted – that is to say, something will be said about the portraits of private citizens – in the next chapter.

The importance of art in the Roman empire, from the time when the principate began in the latter half of the first century BC, can best be understood through the medium of portraiture. And this was appreciated in no uncertain fashion by one Roman emperor after another, starting with the first of them, Augustus, who as a vital element in his introduction of the vast imperial system, based on his own personality cult, arranged that portrait-busts of himself should appear throughout all parts of his empire, as well as in the ‘client’ states that extended beyond its frontiers.3 The artists who so cleverly designed these portraits are almost always unknown, but probably, as hitherto, they were mainly Greeks or at least trained by people versed in the Greek tradition. Acting, no doubt, on orders, or at least conscious of what was required of them, they presented Augustus in a range of different ways: as a modest and constitutionally minded Italian, as priest of one of the antique Roman cults, as a great military commander, or as a grand ruling figure in the line of Alexander III the Great.

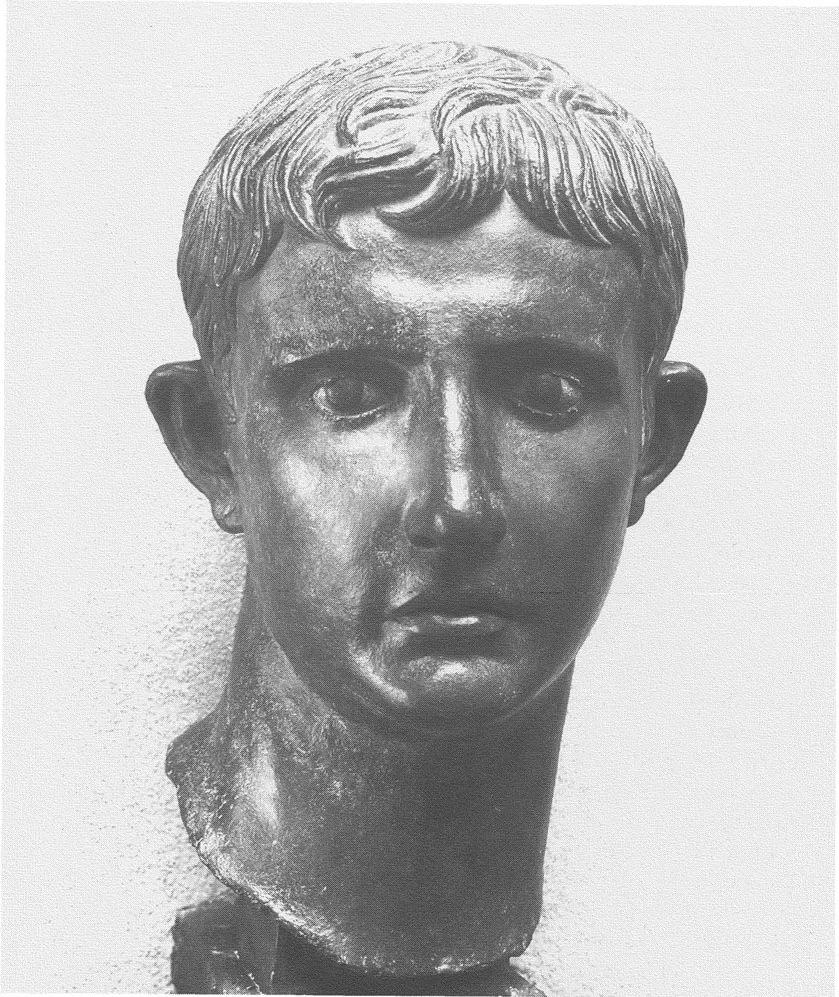

One such bronze portrait4 (Figure 1), somewhat in the last-named tradition (though no doubt owing much to an original Roman commission), was found as far away as the royal palace at Meroe, capital of the Aethiopian (Ethiopian) kingdom, which Roman forces had reduced to a precarious state of dependency. This head, full of tension and passion, portrays Augustus at the age of about 30, and may be contemporary (unless it dates from when he was older, towards the end of his reign), being taken from one of the many statues of him in military uniform, which were to be seen throughout the Roman world. The eyes have glass pupils in a bronze setting, with irises in black and yellow stone: they recall the assertion of Suetonius that Augustus took a great pride in the piercing majesty of his gaze.5 Here, the evocation of the emperor is in the monarchical, Alexander tradition. Indeed, he is seen as a sort of radiant divinity, raised above the real facts of life and of the empire he had knitted together or reinstituted, in a manner which seems to divorce his material being from the reality of the world.

Figure 1 Bronze head of Augustus (31 BC–AD 14) from Meroe in northern Aethiopia (Ethiopia). British Museum.

Augustus had his portrait-busts sent to every village in the empire, and beyond its frontiers as well; and they were also copied locally. Like the coins (which circulated even more freely because they were smaller and cheaper), the busts were seen everywhere, and made it certain that the emperor’s features were familiar to everyone. Sculptors were also careful to represent him in a variety of different lights. This bronze head, with fierce eyes, possibly part of a full-length statue, found at Meroe, across the Egyptian frontier, was perhaps a gift from the emperor to Rome’s client monarch in the northern part of formerly hostile Aethiopia; just as there were client-rulers across many sections of the vast imperial frontiers. Here the emperor is seen as a grand, Alexander-like, imperial conqueror and ruler.

And this great tradition of Roman imperial portraiture continued unabated from the time of Augustus onwards.

A likeness of the ruling prince, as an object of general cult, was to be seen in every camp and city.… After the middle of the third century (perhaps even at the beginning of the empire), it was the custom to send laurel-wreathed and (probably) painted likenesses of a new emperor into the provincial cities. Their arrival was announced by sound of trumpets, a long line of soldiers preceded the richly dressed bearer of the effigy, and the people went out to meet him with lights and censers.… Statues and images of the ruling prince were found throughout the empire, and were especially numerous in all the more important places.… Private individuals also were obliged to show their loyalty in this way.…

During the age of the Antonines [second century AD], the imperial images were to be seen everywhere, ‘in the money-changers’ offices, in the shops and workshops, under the eaves, in the vestibules, and at the windows’. Certainly, as a rule they were … coarsely modelled; but those in wealthy and distinguished houses were no doubt of superior workmanship. For then, in the larger cities, it was by no means uncommon for private individuals to set up statues of the emperors in public.… The rapid and enormous circulation of the imperial images cannot be adequately explained by their conveyance from a number of different centres.… A host of artists and artisans … poured into Rome from the provinces and back again.6

The portraits were often tinted, although the colours have now disappeared.

At all times, then, the government made a special effort to keep their massive subject-populations thoroughly well informed about the ceremonial activities of the emperor’s life; and particular efforts were made to show everyone his features.… No modern dictator distributes his portraits so thoroughly as the Roman ‘Fathers of their Country’ circulated theirs. It was more important for them than for any modern regime to multiply the portraits of the ruler, for these were respected and venerated by the Romans, for religious reasons, to an altogether special and extraordinary extent – perhaps paralleled only in Japan.

So a Roman emperor ensured that there should be a variety of sculptured figures and heads of himself in great numbers in every town and village of the empire. We know of stringent rules against removing or damaging them. For the image of the emperor was sacred: to deface it or treat it lightly was treason: that is why such an effort was made, in every branch of visual art, to create a series of official portraits that were striking, characteristic and recognisable. Sometimes, though not always, realism was the aim. Sometimes the likenesses were excessively flattering. But on other occasions they were not: and it seems strange that the portraits of Nero and Caracalla, for example, should apparently have contented those emperors.7

A good example of a find in a remoter part of the Roman empire is provided by a bronze head of Hadrian (AD 117–38) recovered from the Thames at London Bridge and now in the British Museum. The question of its origin has been discussed.

The head [writes J. M. C. Toynbee] is certainly not Romano-British work … nor can we definitely class it as metropolitan.… The exceptionally broad and heavy face, the extreme stylization of the rows of curls above the brow, and the curious treatment of the back hair, have a provincial look; and the possibility remains that the artist was Gaulish and that the portrait was imported from one of the Gaulish provinces, if it were not cast in Britain by a craftsman invited over for the purpose by the authorities of Roman London.8

This problem of who made that portrait and where, raises general questions. The Meroe head of Augustus had been rather exceptional, because it was found right outside the empire. It must be remembered, however, that imperial portraits also appeared in every Roman province as well. In order that this purpose should be fulfilled, three different methods were employed. Images of the emperor and his relatives, or models, were sent out from Rome. Native artists in the provinces imitated these models – occasionally, no doubt, they were immigrants and travellers,9 but mostly they were local people. And, thirdly, other artists in the same category, not having received such models or, having received them remaining dissatisfied with them as suitable responses to the needs of the province to which they belonged, undertook to make portraits of the emperor and his relatives themselves, not always wholly in keeping with what Rome had prescribed or would prescribe. So the process of ensuring that imperial images were to be found everywhere was a somewhat complicated one. It has been analysed in detail by Paul Zanker,10 who has concentrated heavily on the reign of Hadrian and on his immediate successors the Antonines, although his conclusions, in general, would be equally valid for other periods as well, even if information about them would be harder (or impossible) to obtain. But his work is of value, particularly because it endeavours to draw a line between the three categories of portrait mentioned above, and because, also, it indicates how, and to what extent, the requirements and responses of one region differ from those of another.

The climax was reached in the third century, when the turn of the head of Caracalla (211–17) was something new, and although this was a time of political and military crisis and decline, portrait-busts of Maximinus I (235–8) and Philip (244–9) achieved extraordinary me...