1 Technology and society

- Energy use in society

- Environmental impacts

- Sustainable development

- Negotiating interactions

This introductory chapter sets the scene by looking at the interaction between people and the planet, with the focus on energy use. The ever-increasing pattern of energy use seems unlikely to be environmentally sustainable, in which case we will need to try to negotiate a new way forward. To try to describe some key features of the human–environmental interaction, and how it might be modified, this chapter introduces an analytical model of the various conflicting interests, which is used throughout the book.

People and the planet

Human beings have developed a capacity to create and use tools – or what is now called technology. Technology provides the means for modifying the natural environment for human purposes – providing basic requirements like shelter, food, warmth, as well as communications, transport and a range of consumer products and services. All of these activities have some impact on the environment. The sheer scale of human technological activity puts an increasing stress on the natural environment to the extent that it cannot absorb our wastes, while our profligate lifestyles lead us to increasingly exploit the planet’s limited resources.

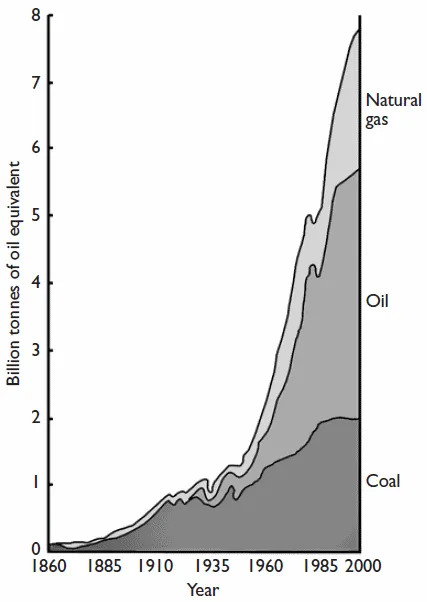

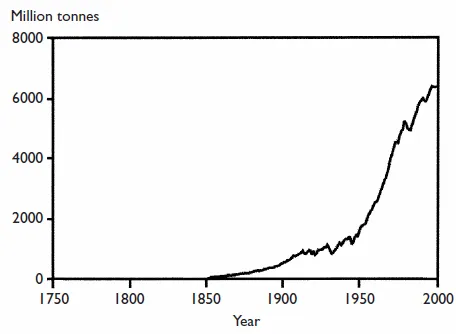

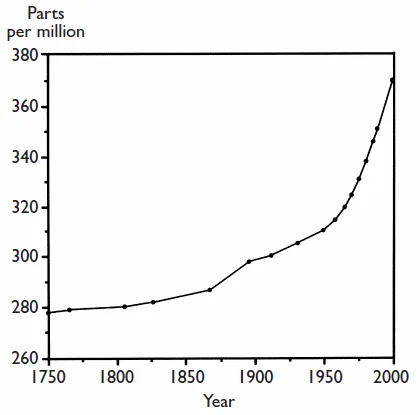

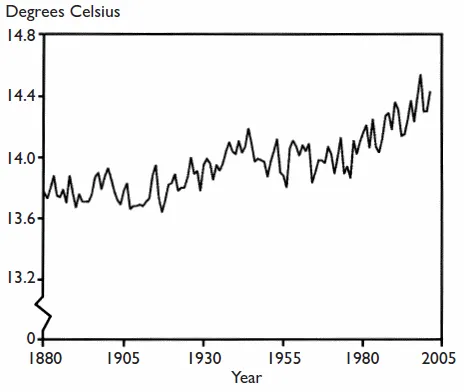

Energy resources are an obvious example of limited resources whose use can have major impacts. Figure 1.1 shows the gigantic leap in energy use since the industrial revolution. Certainly energy use is now central to most human activities and many of our environmental problems could be described in terms of our energy-getting and energy-using technologies. The most obvious environmental impacts are the physical impacts of mining for coal and drilling for oil and gas, and distributing the resultant fuels to the point of use. However, increasingly it is the use of these fuels that presents the major problems. Burning these fuels in power stations to generate electricity, or in homes to provide heat, or in car engines to provide transport, generates a range of harmful gases and other wastes, and also, inevitably, generates carbon dioxide, a gas which is thought to play a key role in the greenhouse ‘global warming’ effect. We will be discussing global warming and climate change in detail later, but certainly there seems likely to be a link between the continuing, seemingly inexorable, rise in global carbon dioxide emissions, shown in Figure 1.2, the gradual resultant rise of carbon dioxide levels in the Natural gas Oil Coal 1885 1910 1935 1960 1985 2000 Year Growth in total fossil fuel consumption worldwide since the industrial in billion tonnes of oil equivalent) Physics Review 2(5), May 1993, based on A. Lashof and D.A. Tirpak (eds), Policy Stabilizing Global Climate, US Environmental Protection Agency. Draft Report to Washington, DC, 1989. Reproduced by of Philip Allan Updates. Updated from 2000 using data from ‘Vital statistics’, Institute, 2002) atmosphere, shown in Figure 1.3, and the continuing rise in planetary average surface temperature, shown in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.1 Growth in total fossil fuel consumption worldwide since the industrial revolution (in billion tonnes of oil equivalent)

(Source: Physics Review 2(5), May 1993, based on data from D.A. Lashof and D.A. Tirpak (eds), Policy Options for Stabilizing Global Climate, US Environmental Protection Agency. Draft Report to Congress, Washington, DC, 1989. Reproduced by permission of Philip Allan Updates. Updated from 1985 to 2000 using data from ‘Vital statistics’, Worldwatch Institute, 2002)

If this trend continues, the world climate could be significantly changed, leading, for example, to the melting of the ice caps, serious floods, droughts and storms, all of which could have major impacts on the ecosystem and on human life. Some of the predictions are certainly very worrying. For example, according to the UK Meteorological Office Hadley Centre ‘failure to act now on Climate Change could mean the Amazon rainforest is devastated; large sections of the global community go short of food and water; many heavily populated low-lying coastal areas are flooded and deadly insectborne diseases such as malaria spread across the world’. However, it is not just a matter of warming, or only a problem for developing countries or tropical areas. There is the possibility that cold water flowing south due to the melting of the polar ice cap could disturb the Gulf Stream which could result in average temperatures in the UK falling by around 10 °C.

Figure 1.2 Global carbon emissions from fossil fuel combustion (in millions of tonnes of carbon)

(Source: Worldwatch Institute, ‘State of the world’, copyright 2002, http://www.worldwatch.org)

Of course there remain many uncertainties over the nature and likely future rate of climate change. Nevertheless, in simple terms it seems obvious that something must change if significant amounts of the carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere. This gas was absorbed from the primeval carbon dioxiderich atmosphere and was trapped in underground strata in the form of fossilised plant and animal life. We are now releasing it by extracting and burning fossil fuels. It took millennia to lay down these deposits, but a large proportion of these reserves may well be used up, releasing trapped carbon back into the atmosphere, within a few centuries.

Figure 1.3 Concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (in parts per million)

(Source: Worldwatch Institute, ‘Slowing global warming: a worldwide strategy’, Worldwatch Paper 91, copyright 1989, updated to 2000 from data in ‘Reading the weathervane’, Worldwatch Paper 160, 2002, http://www.worldwatch.org)

In addition to major global impacts like this, there are a host of other environmental problems associated 1989, updated to 2000 from data in the weathervane’, Worldwatch Paper 160, http://www.worldwatch.org) with energy extraction, production and use – acid emissions from the sulphur content of fossil fuels being just one. Air quality has become an urgent issue in many countries, given the links it has to health. The release of radioactive materials from the various stages of the nuclear fuel cycle represents an equally worrying problem, even assuming there are no accidents. Accidents can happen in all industries – and they present a further range of environmental problems, the most familiar being in relation to oil spills.

Figure 1.4 Global average temperature at the earth’s surface (in degrees Celsius)

(Source: Worldwatch Institute, ‘Reading the weathervane’, Worldwatch Paper 160, copyright 2002, http://www.worldwatch.org)

Ever since mankind started burning wood, air pollution has been a problem, but it became worse as the population increased and was more concentrated in cities, and as industrialisation, based on the use of fossil fuels, expanded. Concern over environmental pollution became 1905 1930 1955 1980 2005 Year Global average temperature at the surface (in degrees Celsius) Worldwatch Institute, ‘Reading the weathervane’, Worldwatch Paper 160, copyright 2002, worldwatch.org) particularly strong in the 1960s and 1970s, in part following some spectacular oil spills from tankers, including the Torrey Canyon off Cornwall in 1967 and the Amoco Cadiz off Brittany in 1979. However, the main concern amongst the emerging environmental movement was over longer term strategic problems: in the mid-1970s, following a series of long-range energy resource predictions (and, as we shall see later, the experience of the 1974 oil crisis), it was felt that some key energy resources might run out, or at least become scarce and expensive in the near future (Meadows et al. 1972).

Certainly, a substantial part of the world’s fossil fuel reserves have been burnt off and a substantial part of the world’s uranium reserves have been used, although, as discussed in Chapter 3, there are disagreements about precisely what the reserves are, and from the 1980s resource scarcity was seen as a less urgent problem. The more important strategic question nowadays is whether what resources are left can be used safely.

Sustainability

The basic issue is one of environmental sustainability: can the planet’s ecosystem survive the ever increasing levels of human technological and economic activity? The planetary ecosystem consists of a complex, dynamic, but also sometimes fragile, network of interactions, some of which can be disrupted or even irreversibly damaged by human activities.

In recent years, following the report on Our Common Future by the Brundtland Commission on Environment and Development in 1987, and the UN Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the term sustainable development has come into widespread use to reflect these concerns. The Brundtland Commission defined it in human terms, as ‘development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Brundtland 1987: 43).

In this formulation, the emphasis is mainly on material levels of resource use and on pollution, but the term ‘needs’ is also wider, and might be thought of as also reflecting concerns about lifestyle and quality of life, as well perhaps as global inequalities and redistribution issues.

Some radical critics of current patterns of energy and resource use go beyond just the issue of environmental impacts, resource scarcity and ecosystem disruption. For some, it is not just a matter of pollution or global warming but also a matter of how human beings live. For them, as well as being environmentally unsustainable, modern industrial technology underpins an unwholesome and unethical approach to life. Technology, at least in the service of modern industrial society, leads, they say, not to social progress but to social divisions, conflicts and alienation, and underpins a rapacious, consumerist society in which materialism dominates. Some therefore call for sustainable alternatives to consumerist society (Trainer 1995). Other critics go even further and, from a radical political perspective, challenge the whole industrial project, and the basic concept of ‘development’, which they see as, in practice, reinforcing inequalities, marginalising the poor, exploiting the weak and disadvantaging minorities, destroying whole cultures and species, and irreversibly disrupting the ecosystem, all in the name of economic growth for a few.

Even leaving extreme views like this aside, from a number of perspectives, the interaction between technology, the environment and society would seem to be a troubled one. Clearly, it is not possible, in just one book, to try to explore, much less resolve, all these issues. Nevertheless, it may be possible to get a feel for some the key issues and factors involved.

A model of interactions

What follows is a very simplified model of the conflicting interests that exist in society, which may help our discussion, in that they may influence interaction between humanity and the environment. Put very simply, there would seem to be three main human ‘domains’ that interact on this planet with each other and with the rest of the natural environment. First, there are the producers – those engaged in using technology to make things or provide services. Second, there are the consumers – those who use the products or services. Third, there are those who own, control, and make money from the process of production and consumption, chiefly these days, shareowners. In addition you might add a fourth, meta-group, that is governments, nationally and supra-nationally, who, to some extent, ‘hold the ring’, i.e. they seek to control the activities of the other human groups, for example by developing rules, regulations and legislation.

Obviously, these are not exclusive groups: in reality people have multiple roles. Producers also consume, even if all consumers do not produce. Producers and consumers may also share in the economic benefits of the production–consumption process, e.g. as shareholders. Moreover, there will be differences and conflicts within each of these groups: not all the producers or consumers or shareholders will necessarily have the same vested interests. However, in general terms, the conflicts between and amongst the three groups or roles will probably be larger than those within each group.

In the past, there has always been a conflict between producers and ‘owners’ – labour versus capital if you like. While the interests of ‘capitalists’ (i.e. owners or shareholders) are to get more work for less money, battles have been fought by trade unionists to squeeze out more pay. A similar but less politically charged conflict also exists between consumers and capitalists/shareowners. Consumers want good cheap products and services and capitalist/shareowners want profits and dividends. Over the years governments have intervened to control some aspects of both these interactions – for example, to limit the health and safety risks faced by workers and to ensure that certain quality standards are maintained in terms of consumer products and services. In parallel consumers themselves have organised to protect their interests.

In some circumstances the interests of consumers and producers may also clash: consumers want good, safe, cheap products and producers want reasonable pay and job security. The ‘capitalists’, i.e. the owners and their managerial representatives, tend to have the advantage in most situations: they can set the terms of the conflicts. Thus they may argue that pay rises will, in a competitive consumer market, lead to price increases, reduced economic performance and therefore to job losses, and in general, they can set the terms of employment and of trade. However, they can be constrained by effective trade unions or by market trends created collectively by consumers.

The environmental part of interaction

So much for the human side of the model. The other element is the natural environment: the source of resources from which producers can make goods for consumers and profits for capitalists. The natural environment has no way of responding actively to the human actors, unless you subscribe to the simplified version of the Gaia hypothesis, as originally developed by James Lovelock, which suggests that the planet as a whole has an organic ability to act to protect itself; the various elements of the ecosystem act together to ensure overall ecosystem survival (Lovelock 1979). Nevertheless, even if the natural environment is passive, it represents a constraint on human activities.

Describing this situation more than a century ago, the German philosopher Karl Marx argued that there could in principle be a conflict between the human actors in the system and the natural environment, but that the constraints on resource availability, and the environmental limits on getting access to resources, were far off. He and his followers therefore devoted themselves to the other more immediate conflicts – between the human actors. Nevertheless, it was recognised that at some point, as human economic systems expanded, they would come into serious conflict with the environment.

You could say that this point has now been reached. The rate of economic growth and technological development has brought industrial society to its environmental limits. Some radical critics argue that such is the desire for continued profit by capitalists that, in the face of effective trade unions on one hand, and tight consumer markets on the other, there has been a tendency to increase the rate of exploitation of nature, thus heightening the environmental crisis (O’Connor 1991).

Certainly, mankind has always exploited nature, just as capitalists have exploited producers and consumers, and this process does seem to have increased. However, just as the latter two human groups have fought back, so now the planet is beginning, as it were, to retaliate, by throwing up major environmental problems. Now, as already suggested, apart from putting constraints on some human activities, the natural environment cannot fight back very actively or positively: it requires the help of human actors, environmental pressure groups and governments to protect and promote what they see as its interests.

The model reviewed

The model is now complete: there are the three conflicting human groups (producers, consumers and investors/shareholders) locked into economic conflict; governments active nationally and globally to varying extents; and the natural environment. The environment is mainly dependent for protection on the interventions of people and governments, but perhaps the environment is also able to constrain human activities by, as it were, imposing costs on human activities if these disturb key natural processes, and, in the extreme, making human life on earth unviable.

The issues facing those involved with trying to diffuse this complex situation are many and varied, and, by focusing on economic conflicts, our ‘interest’ model only partly reflects the political, cultural and ideological complexity of society. In reality people occupy a range of roles: they are not just consumers, producers or shareholders. Moreover, while our model may reflect some of the economic conflicts between various groups within in any one country, it does not reflect the conflicts amongst nations or groups of nations. For example, there are the massive imbalances in wealth and resources amongst the various peoples around the world, and conflicts over ideas about how these imbalances and the in...