![]()

1

Editorial Introduction

John Weiss and Michael Tribe

Introduction

Industrialisation is central to structural change. Historically, as most economies have evolved, workers have left the land to take up jobs in factories, mines or construction sites, attracted by the possibility of higher and more stable wages. Early theorists of development saw industry, most particularly its manufacturing branch, as critical to the transition of economies from low income to higher income status because of the higher productivity and technological dynamism associated with manufacturing.1 When Arthur Lewis wrote of the possibility of a modern sector absorbing surplus labour at a constant real wage he had in mind that manufacturing would be the dominant ‘modern’ employer (Lewis, 1954). Similarly, when Ragnar Nurkse envisaged a group of new activities supporting each other in a pattern of balanced growth, these were to be principally new manufacturing activities (Nurkse, 1958). From the opposite perspective, when Albert Hirschman identified the key role of linkages in stimulating the new investment he pointed out that manufacturing creates more linkages than other branches of activity (Hirschman, 1958). Hence there is little doubt that from an early stage, industrialisation and economic development were seen as inextricably linked.

On the other hand, much of the early development literature stressed the serious obstacles to successful industrialisation. Having a large labour surplus clearly meant that low cost labour was available, but other preconditions in relation to funding for investment, and in particular the foreign currency needed to import the equipment needed for capital assets, were stressed. The perceived difficulty of generating export revenues in order to obtain this foreign currency was rationalised as a ‘balance of payments constraint’ on growth (Thirlwall, 1980). In addition, the unbalanced economic and political relations in the world economy were seen by some as posing major obstacles to the successful growth of poor countries. The interests of the rich centre and poor periphery were seen as in conflict, through an international trading system that kept the latter dependent on the export of primary commodities and through the activities of rich-country firms which dominated the domestic markets of manufactures of poor countries, either though imports or by displacing any nascent local capacity (Baran 1957).

From a contemporary perspective many of these arguments appear outdated and simplistic. Economic growth is now understood to be about a great deal more than the application of factors of production, with the role of technical change and the institutional base of an economy given prominence as key fundamentals. The role of economic policy in overcoming balance of payments difficulties and the potential for mutually beneficial trade are now better understood. Ownership of companies now appears to matter much less than other characteristics of their operations. However, this does not mean that all issues are resolved and that the most effective route to industrialisation has been mapped out. Progress in countries accepted as poor or ‘developing’ in 1960, for example, has been highly uneven with both success stories and disappointments, and it is important to address this difference in experience.2

This Handbook brings together a set of chapters on different aspects of industrialisation experience in these countries to give a contemporary perspective on industrialisation. These chapters focus on key issues from the academic and policy literature, combining a focus on general issues with a number of specific country experiences. This introductory chapter sets the scene by surveying the scope of the book. It begins with a discussion of why manufacturing has been seen as having a special role in initiating economic growth and structural change. A second section gives a broad comparison of the extent of industrialisation in 1960 and the present. A third section illustrates the unevenness of the industrial development of the past fifty years and the impact this has had on structural change in different economies. Given that in many poor or developing countries many manufacturing firms are small, a fourth section addresses the small-scale sector and its particular problems. The world economy has opened up considerably over this period in relation to trade and capital flows in a process now termed ‘globalisation’. The important implications of this process for industrialisation are discussed in a fifth section. Of all the factors driving economic growth, technology and technical change are often considered the most critical. Poor or developing countries by definition are not technology innovators; however, as ‘latecomers’ they have the opportunity to draw on technology developed elsewhere. The role technology plays and has played in industrialisation is the focus of a sixth section. There is much evidence that policy towards industry matters and section seven discusses aspects of policy commencing with the wider debate on ‘industrial policy’ as a means of supporting and encouraging industrialisation and then moving to issues of regulation and competition policy. A final brief section concludes.

Why manufacturing?

A starting point for discussion of the theoretical approaches to ‘industrialisation’ can be provided by the observation that the process of economic growth and development is associated with significant increases in the level of labour productivity.3 In turn, increases in labour productivity arise from the application of changes in production technology, from the introduction of adapted and new products, from the application of higher levels of investment to the production process, changes in the organisation of production, and from higher levels of skill embodied in the labour force. However, despite this focus on a contrast between traditional and modern segments of an economy there is a long tradition in economics, discussed in more detail in the chapter by Weiss and Jalilian, which argues that manufacturing industry is critical, particularly at relatively low levels of income per capita. This ‘engine of growth argument’ rests critically on the potential for technical change and productivity growth within manufacturing, arising from the scope for specialisation, learning and product diversification within the sector.

The normal historical pattern has been that in poor countries the share of manufacturing in total economic activity is very low, that as growth occurs and workers move out of agriculture it rises rapidly, but that once a threshold income level is passed the relative share of manufacturing starts to decline as demand shifts towards services. Recent experience has questioned some of these assumptions. As discussed in the chapter by Haraguchi, across all countries there is evidence that the relationship between a country’s income per capita and the share of manufacturing in GDP has been weakening so that for a given level of income the manufacturing share predicted from cross-country analysis is lower than in earlier time periods. This is particularly the case where employment shares are concerned, with a weakening of the relationship between employment and manufacturing growth and absolute declines in manufacturing employment in some high income economies: the chapter by Tregenna in this volume discusses these issues. Furthermore, in recent decades rapid productivity growth has occurred outside manufacturing, in large part due to the application of computer-based technologies. The chapters by Timmer et al. and by Weiss and Jalilian in this volume produce detailed evidence on productivity levels and growth. Timmer et al. show that the level of manufacturing productivity remains higher than in services in all developing regions. The relative expansion of services has had a positive impact on overall productivity growth due to a static reallocation effect (as service productivity levels are above the economy-wide average) while the dynamic aspect of this reallocation is negative (as productivity growth in services is lower than in the declining sectors, principally manufacturing). However, there are regional differences and the net contribution of services to the growth of overall productivity exceeds that of manufacturing in Africa, whilst it is well below it in Latin America and roughly equal to it in Asia. Weiss and Jalilian disaggregate the productivity performance of services and show that it has been more rapid in some branches of services than in others. The implication is that the dynamic ‘modern’ branches of a low income economy need not all be concentrated within manufacturing and that parts of the service sector are showing the sort of dynamism associated in the past with manufacturing.

Nonetheless, recent empirical work has confirmed the importance of manufacturing to economic growth, particularly at lower income levels, where it can be an important source of employment at productivity levels well above those offered in the rest of the economy. At higher income levels it represents the key dynamic internationally traded activity. A shift in economic structure (whether in terms of share of value-added, employment or exports) in favour of manufacturing has been found to be associated with more rapid economic growth. This has been evidenced for growth accelerations (periods of sustained GDP growth). In part this may reflect a shift towards greater export activity driven by manufactured exports. Also shifts in economic structure in favour of manufacturing have been associated with higher aggregate productivity growth in Asia, and shifts against manufacturing have been associated with lower aggregate productivity growth in Africa and Latin America.4 It should be noted that some empirical work also links the service sector share in GDP with growth accelerations, so the impact may not be unique to manufacturing (Timmer and de Vries, 2009).

Manufacturing post-1960 and uneven development

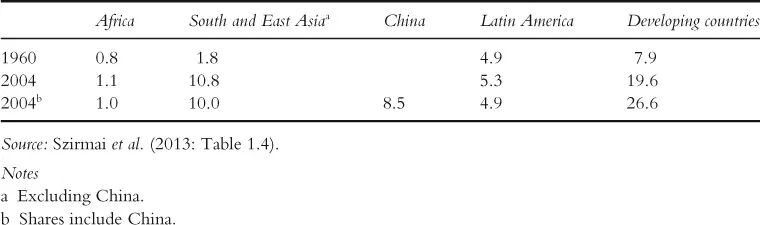

Countries that were identified as ‘developing’ in the 1950s accounted for only a very small share of global manufacturing. Precise statistics are unavailable, but one careful estimate suggests this was no more than 8 per cent in 1960, excluding China, where comparable data were unavailable (Table 1.1).5 Unevenness was already present on a regional basis in 1960 with Latin American developing countries providing nearly 5 per cent of global manufacturing value-added, African countries 0.8 per cent and South and East Asian countries (excluding China) 1.8 per cent. By 2004 the picture was very different, with the same set of countries (excluding China) now providing just under 20 per cent of global manufacturing. The shares of Africa and Latin America were both slightly larger than in 1960, but the share for Asia was as much as 9 percentage points higher, driven by the rapid industrialisation in Korea, Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan together with more modest growth, but a large absolute increase, in India.6 The relatively recent impact of China on the world economy is reflected by the fact that it accounted for 8.5 per cent of global manufacturing in 2004.

Table 1.1 Estimates of percentage share of developing countries in world manufacturing value-added, 1960–2004 (constant 1990 prices)

Alternative estimates distinguish between ‘industrialised’ and ‘industrialising’ economies, with the former higher income group now including Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Malaysia as graduates from the developing-country classification due to their rapid growth and industrial development. With China still included in the group, the industrialising countries accounted for 18 per cent of global manufacturing value-added in 1992, whilst this share nearly doubled to 35 per cent in 2012. In 2012 the poorer, or least developed, countries in the industrialising group accounted for 9 per cent of the total value-added of this group or little more than 3 per cent of global value added.7 This expansion of manufacturing was not only in simple low technology labour-intensive activity, since there are estimates to suggest that some developing countries also increased their share of world value-added in medium and high technology branches of manufacturing. In Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa where industrialisation has proceeded far more slowly, and has actually regressed in some countries, this was not the case as their share in these branches fell.8

A similar pattern occurs in relation to manufactured exports. The share of the developing-country group in world exports of manufactures was estimated at just below 6 per cent in 1963 and this rose rapidly to just below 31 per cent in 2005.9 By region, Latin America’s share rose by 3 percentage points over this period, whilst that of Africa fell by 0.5 percentage points from a low base. China is not included in the 1963 figures, but in 2005 its share in world manufactured exports was 9.4 per cent. Using the ‘industrialised’ and ‘industrialising’ classification, the share of the industrialising group in world manufactured exports rose from 14 per cent in 1997 to 30 per cent in 2011, although nearly half of the share in 2011 (or 13.5 per cent of world exports) was accounted for by China.10

The employment effects of manufacturing are an important source of income for the poor and their families in economies at relatively low levels of income, which is an issue discussed by Athukorala and Sen in this volume. However, given its relatively high productivity, the share of employment accounted for by manufacturing in most countries is well below its share of value-added. Data from the UNIDO database suggest that depending on an economy’s income level the share of manufacturing in total employment lies between 10 per cent and 20 per cent, whereas the share in value-added can reach 30 pe...