1 The study of teaching

Introduction

We can, already, recognise competent, successful and excellent teaching. Prospective schoolteachers who satisfy a range of standards set by the Teacher Training Agency (TTA 1997b) are competent. Good and excellent teachers divide from the satisfactory via common ‘Office for Standards in Education' criteria (Ofsted 1995): all school inspectors judge poor, acceptable and first-rate teaching using the same framework. Lately, the Department for Education and Employment (DfEE) has named six areas for excellence meant to guide the assessment of Advanced Skills Teaching (Sutton et al.2000). These are: ‘achieving results; subject knowledge; lesson planning; motivating pupils and maintaining discipline; assessment and evaluation; supporting and advising colleagues' (Sutton et al. 2000:418–419). So the TTA, Ofsted and DfEE, together, give us reliable ways of sorting out what is and is not quality teaching.

But standard guides, alone, do not deal with classroom specifics. Even the most detailed frameworks (e.g. Hay McBer 2000) have to be applied to particular circumstances by professionals themselves. Elements of practice that school inspectors are trained to inspect (planning, relationships, methods, work-setting, pace and subject knowledge) span broad classes and combinations of skill. Nothing is assumed about the precise content of lesson objectives, pupil—teacher relationships and strategies likely to work, what makes a lesson well paced or betrays how deeply into subjects teachers should reach. Inspectors—like all others who find their judgements prey to the unforeseen and unpredictable— accept that there are many ways to teach well. Teachers are paid to bring about learning in pupils, and factors that ease or impair learning are legion, since children enter schools with widely varying capabilities and ambitions, born from culturally and economically diverse backgrounds.

Admittedly, good teachers keep a weather eye open for anything likely to affect pupil learning. This fact preserves the utility of TTA criteria. For it is teachers who must ‘ensure effective teaching of whole classes, and of groups and individuals within the whole-class setting, so that teaching objectives are met' (TTA 1997b: para. 2f, italics added). Teachers have to take whatever steps are needed to safeguard their success. Yet, on the face of it, no amount of ‘taking into account' of pupil attitude and capability will ‘ensure' that teaching objectives are met, where ‘ensure' means more than teachers doing their best. No action, however informed or sophisticated, can oblige learners to behave in ways contrary to their own inclinations, even if major factors affecting teaching-learning circumstances are known. Strictly speaking, teaching and learning are independent processes. One human being's behaviour does not cause improvements in another in an unmediated fashion (except at primitive levels where ‘laws' of conditioning prevail), for each human being is sovereign in his or her own mental domain. We would not wish it otherwise. We will still insist that teachers do their best to ensure learning. But doing one's best is a world away from ensuring effective teaching. And this realisation forces us towards two connected conclusions.

First, we must honestly square up to the limited control teachers have over some central conditions for learning, owed to pupil and school-specific factors. No less urgently, we should check out these conditions in terms of the known ways of dealing with them. Saying that a teacher's capacity for ensuring learning is limited does not deny it altogether. It is to be hoped that the more we know about the limits of pedagogy the more we can strengthen its influence within those limits. And if it should prove that learners' readiness to learn is the one essential ingredient of teaching success, we might give more regard to methodologies which duly respect it—even though such methodologies are not presently in vogue. English educational policies are preoccupied with sharpening teacher performance through legislated measures linked to an assessmentled accountability (see Broadfoot 2000). This fixation on remedying teacher shortcomings may have distracted us from helping the same teachers respond intelligently to demands arising from pupils themselves —apart from any duties practitioners might have to the teaching of subjects, hitting exam targets or whatever.

It is a truism that changing times lead to changing expectations. But changes in expectations should not mean always starting from scratch. There is no virtue in dismissing teaching approaches still found in classrooms just because they are out of tune with the latest thinking. It may be that truly innovative techniques, arising from new rationales for learning and intellectual development, work because they extend or develop teachers' existing thinking rather than contradicting it. What will aid us to a grasp of the nature of good and excellent teaching is an in-depth look at the way teachers actually teach—without prejudice. And we might look hardest at what can be done to give credence both to our public expectations of schools and to the challenges arising just because they deal with other (usually immature) human beings who have minds and needs of their own.

Three approaches to the study of teaching

As introduced, we must resist the temptation to short-cut theorising about practice by moving too quickly to actual recommendations (especially where theories have been overlooked by legislation). We may not need to disinter old quarrels about incompatible positions, since recent thinking has brought us to a point where we know why some positions might remain incompatible yet might not stop us reaching conclusions about practice. If we stick to basics—the interactions between teachers and pupils vis-à-vis school subjects found in all school settings— there are only three general ways teachers can approach their task. And it is these easily stated ways which guard strongholds of competing professional ideals (their obviousness witnesses to their abiding effects).

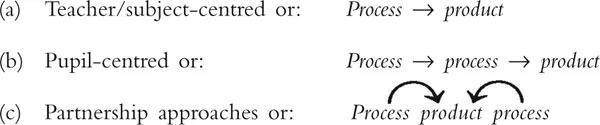

First, teachers can work through some form of top-down imposition. Second, they can shrink from imposition in order to sanction learners' own viewpoints. Third, they can structure a collaborative system which makes a ‘middle way' between imposition and learner-centredness. In so far as third way options dominate modern thinking, there is devil in the detail of what these might actually mean. There are strong and weak forms of imposition, middle-of-the-road and extreme types of ‘progressivism'. So to seek stable midway points between the two begs questions of definition and practicality. But, staying with generalities pro tem, the three options introduced are (paradigmatically) a teacher or subject-centred approach; a learner-centred approach; and a partnership approach (compromising between teacher and learner-demands).

An easy way to compare each of these is by isolating teacher and learner decision-making as ‘processes', while making learning and other desirable outcomes a ‘product', as follows (see also Silcock 1993a).

With the first paradigm, a teaching process outputs directly into a learning product; and in so far as intermediaries affect success it is thought in teachers' remit to deal with these. With the second, it is selected intermediaries, notably the skills, attitudes and commitments of pupils themselves, which give results (learning outcomes): these have the decisive role in the pedagogic equation. So it is on these which teachers must concentrate. With the third, pupil and teacher-actions are integral to a system where each functions optimally in tandem with the other. Two agencies work effectively because they work together. What is promised by insulating the paradigms from each other is that each will faithfully deliver particular outcomes. It may not be a question of whether there is one sort of ‘quality' teaching, but what, exactly, each promises to any teacher pursuing excellence.

As a preliminary to closer study, it is worth exploring this possibility for each paradigm in turn.

An introduction to teacher-centred approaches

What seems inviting about the process—product paradigm is its stand on a ‘zero tolerance' for educational failure. If teachers can really dictate outcomes, the highest fence in the educational stakes is cleared at a bound, at least in principle. An uncluttered ‘cause—effect' connection is banked on by anyone believing that standardising curricula is critical to raising standards, given that this belief practically equates clarity of task with curricular delivery. Once teachers know exactly what is expected of them they have success in their sights. Should they, still, fail, they can rightly be regarded as chief culprits for their own failure. Such teachers can be dismissed, admonished or retrained.

A likely flaw in what is the simplest possible pedagogic formula has already been mentioned. It is not that teachers cannot manage pupils' learning at all, just that it is hard to see how they can ever be sure they will succeed. The premise that one group of human beings (teachers) ‘manages' the minds and actions of another (pupils) must always be qualified, for it makes all of us potential arbiters of other people's actions and decisions while remaining uncertain arbiters of our own. Yet this ‘performance management' formula is seldom questioned by those outside professional circles. Parents often take for granted that any difficulties raised by pupils' intransigence can be ironed out somehow (as Winch 1998 says). They believe (rightly, in Winch's view) that there are practical solutions for all such problems. Of course, to say this belief is not always true, doesn't mean it isn't usually true (Winch and Gingell 1996). Such qualified approval might confirm the first paradigm as one well suited to present-day schools.

But no one would or could argue that today's schools never fail their pupils. Each year, a number of students complete formal schooling with few qualifications; some can neither read nor write at even minimal levels (Pring 1986). Although this failure of educational policy may have other causes than unrealistic expectations of teachers, it does leave open the possibility that unreasonable expectation is a main cause.

An introduction to learner-centred approaches

Kelly (1989), following Stenhouse (1975), has done much to popularise the idea that teachers neither can nor should ‘deliver' a set curriculum but are better occupied teaching students how to access curricula for themselves. Core learning processes are outputs we should want, not specified ‘content' which, in any case, few are likely to agree about (Kelly 1995). Importantly, such proposals do not diminish the school or teacher's role. For although pupils are treated as agents for their own learning, mediating or facilitating that agency is in the remit of teachers. ‘Contextualising' learning or teaching for independence replaces knowledge transmission or performance-management as role-definitions. So if learners fail we can, still, name the teacher as culpable. We can still condemn uncertain empowerment strategies, poorly resourced workplaces, or whatever.

However, prescriptions inferred from the ‘process' model are rather tenuously linked to teacher-action and learning outcomes. The paradigm makes requirements for setting and achieving objectives differ between pupils; and there are real uncertainties for teachers working informally in knowing exactly what does count as a successful outcome. If it is in the dispensation of learners, what might we believe indisputably are criteria for teaching effectiveness? Do these lie in the attitudes fostered in learners or in their actual achievements? And does it matter what those achievements are? Or should pupil-empowerment itself become our teaching goal, disregarding the content of what ultimately is learned? To give to learners decision-making powers may overburden them, no matter that they have been educationally enfranchised. Critics (e.g. Alexander 1992) see as bedrock the requirement of a modern educational system that types of learning are non-negotiable (e.g. literacy and numeracy skills); and to offload responsibilities onto learners—albeit creditably armed with positive attitudes and personally useful skills—is to bypass the decisions which matter most. Moreover, to opt for strategies that hit desired targets indirectly, creates a more hazardous set-up than that created by the process-product ideal. Teachers, knowing they will be held accountable if they fail, may find a thoroughly learner-centred curriculum just too risky to contemplate.

Raising such objections does not damn altogether process-based teaching. It encourages us to limit known difficulties while retaining inherent strengths. What commends the classic ‘learner-centred' paradigm is its full hearted acceptance of the socio-psychological and ethical deficits earned by teachers exerting top-down control over pupil learning. By not glossing over these, it helps us see where further progress might be made. For, to press on towards the third paradigm, one might speculate that it is reasonable for us to concede some basic misgivings about controlled curricular delivery while, still, insisting pupils meet agreed targets. Surely, all we need do is more carefully demarcate teaching and learning roles? If learning is something learners have to do for themselves this does not mean they do so in an academic vacuum: their capacity and appetite for learning must, somewhere, benefit directly from pedagogic skill. A properly ‘dual-referenced' rationale, once written, will guide both teachers and learners towards common goals in practically useful ways. If plainly stated, it should set down rules not to be ignored without doing injury to the paradigm itself.

An introduction to partnership (dual-referenced) approaches

It seems sensible to think that educational outcomes are won by interchanges between curricular partners with complementary roles. School teaching and school learning are conceptually bound together, so they must interrelate practically too. And although partnership work takes for granted that teaching skill alone cannot deliver quality outcomes, it gives just as much credence to doubts about ‘empowered' pupils hitting learning targets consistently enough to satisfy parents or politicians. Its rationale condemns both classic paradigms. What, purportedly, it does not do is fudge the issue of whether it is teachers or pupils who matter most to educational success, for it refuses to come down on one side or the other. No matter how autonomous a pupil is, the fact a state-financed regime exists means due note is taken of publicly agreed aims and the rule-governed way in which schools operate. Similarly, no matter how charismatic or skilled a teacher, internal pressures on learners (from social and psychological sources) with which the learners themselves have to cope are respected. The onus on realising curricular aims, therefore, moves from teachers or pupils alone and becomes the responsibility of both, though not always in equivalent measure in all circumstances.

It is common enough in schools for teachers to collaborate with each other, with parents and (in a rather different sense) with pupils. Leaving aside for the moment merits of types of collaborative work per se, the partnership approach outstrips the practical benefits of collaboration to become a major paradigm of good practice (or a ‘new' professionalism: Hargreaves 1994; Quicke 1998). At a level of personal achievement, pupils fashion their mental worlds and learning skills through their own agency. But (at least in institutional settings) they do so within shared, culturally rich frameworks (resourced especially by teachers and parents) powerfully affecting what they do. This paradigm (related to a sociocognitive process called co-construction) finds an implacable dualism at the heart of schooling, counterpointing the roles of learners with teachers, then extending their relationships to include important others, in a complex though comprehensible pedagogic enterprise.

What knowledge we have of the approach suggests it might be a break-through in teaching methodology (Silcock 1999). Because it is unremittingly co-operative (learning is always ‘co'-constructed), it invites a bipartisan form of teaching not simply to satisfy the whims of a teacher or the variable demands of circumstance but as a modus operandi. It imposes dyadic controls, rule operations, curricular decision-making and so on. Its binding, contractual nature gives parity to participants by rule: within true partnerships, constraints of rule and relationship affect both agents. It isn't only that learners are constrained by what teachers do, teachers are just as bound by learner-actions and demands.

Unfortunately, deciding that teaching and learning are bound together makes sense only if one can pin down precise terms in which they are and convincingly illustrate benefits. Otherwise, contentions become merely fatuous, reducing to the self-evident fact that teachers and learners must both engage in any organised teaching situation. One suspects that teachers opt sometimes for top-down management and sometimes for learner empowerment because a degree of single-mindedness guarantees results of some sort. There are obvious dangers in trying to achieve too much at once. In the end, we might decide to deal with the currently fashionable topic of what makes for excellent teaching just by reasserting the profoundly variable nature of teaching. Satisfaction might be limited to showing how the different paradigms constrain teachers trying to teach competently, successfully or reach excellence. Model-specific rather than general factors may unite them. This has to depend on what we are looking for when we look for quality of teaching or level of success.

Different standards of teaching

The interplay between generic and contextual factors

Competent teachers are not always successful, and teachers can enjoy success despite their lack of skill. But this does not by itself make teaching a random or irregular craft. Nor does it make generic skills irrelevant. Reasoning in this way would be defeatist in the extreme. It is a fair supposition that those who are effective in classrooms will be largely competent, while those who approach excellence will to a high degree teach effectively. So there is likely to be a linear progression from teaching competence to excellence.

What potentially confuses any anal...