1 Sport and economics

Introduction

This book is about the economic analysis of the sports market, i.e. the demand for and supply of sporting opportunities. Sport is now recognised as an important sector of economic activity, part of the increasingly important leisure industry which accounts for over a quarter of all consumer spending and over 10 per cent of total employment in the UK, and brings in over £20 billion per annum in foreign exchange. Sport is not the largest sector of the leisure industry, but it is among the fastest growing.

Many articles and books have been written about money in sport, and when the phrase ‘economics of sport’ is used, most people think of it as the analysis of the ‘sports business’, or the élite sector of the sports market that attracts massive amounts of money through sponsorship, payments for broadcasting rights, and paying spectators. Although money generated through professional sport, international sports competitions, and the televising of major sports events is both substantial and increasing, this is a relatively small part of the total sports market.

It is relatively easy to identify the amounts of money involved at the élite, increasingly professional, end of the sports market. It is less straightforward to identify the expenditure on sport in a country as a whole and the balance between the élite of the sports market and the broad base of recreational sport. We will show that it is now possible to estimate the money value of the broad flow of resources in and out of sport, and such estimates indicate that the economic value of the recreational base of sport far exceeds that of the top of the sports hierarchy.

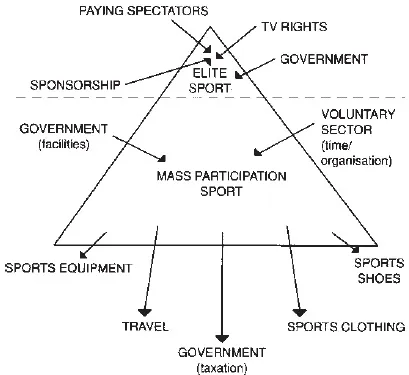

Figure 1.1 shows the hierarchical nature of the sports market, with a relatively small group of top athletes at the top of the pyramid competing in national and international competitions. At this level, money flows into sport from sponsorship, from paying spectators, from the National Lottery, and from television companies eager to broadcast this top level of competition.

Although the élite end of the sports market appears to be essentially commercial, it is also subsidised by government. Economics can help to provide a rationale for and to assess the cost-effectiveness of such subsidy. Every country wishes to see its own sportsmen and sportswomen as international champions. There is a national demand in every country for international sporting success. Governments fund the top end of the sports market in order to ‘produce’ sporting excellence and international sporting success, both through their own direct expenditure and through their control of sports lottery funds through government agencies.

Figure 1.1 The sports market.

At the bottom end of the pyramid we have recreational sport: people taking part in sport for fun, for enjoyment or maybe in order to get fitter and healthier. This part is also subsidised by government (including lottery funds), but predominantly by local government through subsidies to sports facilities in the community and in schools. Again, economic analysis explores both the rationale and the efficiency of such government intervention. Government subsidies at this level are much higher than those directed at the élite end of the sports market. Figure 1.1 also identifies another important source of resources into sport: the voluntary sector. The resources the voluntary sector contributes to sport are massive, but the most important resource is the time that volunteers contribute to sport without payment, and it is not easy to put a monetary valuation on this (although we do attempt it in this book!).

Although government and the voluntary sector support the recreational end of the sport market, there are substantial monetary flows from sports participants to the commercial sector through their expenditures on sports equipment, sports clothes and sports shoes. These same participants also contribute to government revenue in the form of taxation on sport-related expenditures and incomes. In fact, in Britain the amount that sportspeople give back to the government in taxation through sport participation is greater than the amount of government subsidies to sport. Sport gives more to government than government gives to sport.

One final important area that is just starting to be recognised and measured as a sport-related expenditure is sport-related travel. Leisure travel is an important part of travel expenditure, accounting for over 30 per cent of all travel expenditure. Sport-related travel has increased its share of all leisure travel consistently over the past 20 years so that it now accounts for about 10 per cent of leisure travel.

Figure 1.1 indicates the complex nature of the sports market. The supply side of the sports market is a mixture of three types of provider: the public sector, the voluntary sector, and the commercial sector. Government supports sport both to promote mass participation and to generate excellence, but government also imposes taxation on sport. The commercial sector sponsors sport both at the élite level and at grassroots. Some of these sponsors (e.g. Nike, Adidas, Reebok) do so in order to promote their sports products and receive a return on this sponsorship through expenditure by sports participants on their products. Most of sports sponsorship is, however, from the non-sports commercial sector (e.g. Coca-Cola, McDonalds), where the motives for the sponsorship are less directly involved with selling a product to sports participants. Squeezed between government and the commercial sector is the voluntary sector, putting resources into sport mainly through the contribution of free labour time, but needing also to raise enough revenue to cover costs since it cannot raise revenue through taxation as government can.

If the supply side of the sport market is complicated, then so is the demand side. The demand for sport is a composite demand involving the demand for free time; the demand to take part in sport; the demand for equipment, shoes, and clothing; the demand for facilities; and the demand for travel. Taking part in sport involves, therefore, the generation of demand for a range of goods and services which themselves will be provided by the mixture of public, commercial, and voluntary organisations discussed above.

To this complexity of the demand to take part in sport can be added the complication that the sports market is a mixture of both participant demand and spectator demand of different types. As we move up the hierarchy towards élite sport, there is an increasing demand to watch sporting competitions. Some of these spectators may also take part, but many do not. The spectators may go to a specific sports event, or watch at a distance on television. Alternatively, they may not ‘watch’ at all, preferring to listen on the radio or read about it in newspapers. All of these activities are part of the demand side of the sports market.

In fact, market demand is even more complicated than this rather complex picture, since Figure 1.1 represents only the flows into and out of a national sports market. Increasingly it is more appropriate to talk about the global sports market. A small, but increasing, part of every country’s sports market is international or global. There already exist sporting competitions that are of truly global dimensions: over two-thirds of the world’s population (over 3.5 billion people) watched some part of the global television coverage of the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games. The cumulative television audience for the 1998 football World Cup was over 40 billion. Equally there are commercial companies that produce, distribute, and market their product on a global basis. Nike designs its sports shoes in Oregon, USA, contracts out the production of these shoes to factories in Thailand, Indonesia, China, and Korea, and markets the shoes on a global basis using a symbol (the swoosh) and, in the past, three words that have been understood throughout the world (‘Just Do It’). Nike, in 1997, rose to 167th in the world’s top 500 companies with a market capitalisation of $17.5 billion.

This book attempts to increase understanding of this complex, increasingly global, market. However, at this early stage it is worth pausing to consider what we mean by sport.

The definition of sport

All researchers concerned with the study of sport face the difficult problem of how to define sport. Sport is a part of a broad range of activities that we call leisure. Leisure researchers, however, have struggled for some time to answer the simple question: what is leisure? Many leisure researchers would argue that it is impossible to have an objective definition of a leisure activity since it depends crucially on the perceptions of the individual participant. The argument is that the same activity can be leisure to one person and non-leisure to another. In fact, it would be quite possible to write a whole book on the question of the definitions of leisure, recreation and sport; but we do not intend to do that here.

The European Sport for All Charter (Council of Europe, 1980) gives a classification of activities that might solve the problem, by dividing sport into four broad categories:

- competitive games and sport which are characterised by the acceptance of rules and responses to opposing challenge;

- outdoor pursuits in which participants seek to negotiate some particular ‘terrain’ (signifying in this context an area of open country, forest, mountain, stretch of water or sky); the challenges derive from the manner of negotiation adopted and are modified by the particular terrain selected and the conditions of wind and weather prevailing;

- aesthetic movement which includes activities in the performance of which the individual is not so much looking beyond himself and is responding to the sensuous pleasure of patterned bodily movement, for example dance, figure-skating, forms of rhythmic gymnastics and recreational swimming;

- conditioning activity, i.e. forms of exercise or movement undertaken less for any immediate sense of kinaesthetic pleasure than from long-term effects the exercise may have in improving or maintaining physical working capacity and rendering subsequently a feeling of general well-being.

The Council of Europe’s European Sports Charter, adopted in 1992, uses a more concise definition:

‘Sport’ means all forms of physical activity which, through casual or organised participation, aim at expressing or improving physical fitness and mental well-being, forming social relationships or obtaining results in competition at all levels.

The main question to be answered is how to distinguish between active sport and more general leisure and recreation activities. Certain activities fall easily into one category or the other. Football, athletics, and gymnastics are clearly Olympic sports and will be recognised by every country as active sport. Going to the cinema, going out for a meal, and watching television are other activities done in leisure time that are clearly non-sport. It is at the margin the problem arises. Are darts and snooker sports or leisure activities?

It could be argued that they are sports, since television coverage of such activities occurs in sports programmes, and newspaper coverage is in the sports section. The activities are also competitive, with well-publicised world championships. In countries where these activities are popular, they are normally included as sports in sports participation surveys. However, they involve little or no physical exertion, so they do not fulfil the criterion of ‘physical activity’.

Another set of activities, which are physical but not competitive, are also often included in national sports participation surveys. Activities such as gardening are physical but generally regarded as non-sport, although this activity is included in some participation surveys, normally when the survey is of ‘sports and physical activities’ rather than just sports. More problematical in this category of activities is walking. Although many types of walking, such as strenuous walking in mountains and the countryside, are clearly active recreation giving the same sort of health benefits as sport, there is a serious problem in interpreting the category ‘walking’ when it appears in sports participation surveys. Normally, it will represent a wide range of types of activity, some of which we would not want to include as sport. Walking is an activity that is particularly problematical for international comparisons of sports participation, since it tends to have a very high participation rate in northern European countries and a relatively low rate in central and southern European countries.

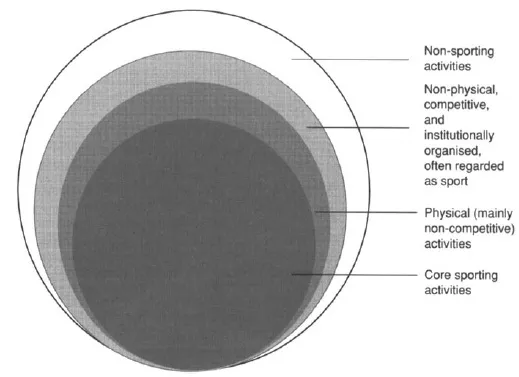

Rodgers (1977) considered the same problems and argued that four basic elements should ideally be present in a sport, and the first two should always be present. Sport should involve physical activity, be practised for a recreational purpose, involve an element of competition, and have a framework of institutional organisation. To these we add the criterion of general acceptance that an activity is sporting, e.g. by the media and sports agencies. Rodgers developed a core list of sporting activities that could be used for all countries and suggested that a supplementary list could be drawn up to fit the specific needs of each country. The general categorisation of sports and non-sports is shown in Figure 1.2.

The inner circle represents activities that are accepted as sport in all countries and fulfil all of Rodgers’ criteria. The second circle represents those which cannot be classified as core sport but have the two key characteristics of being physical and recreational, as well as commonly being regarded as sporting activity.

Figure 1.2 Conceptual classification of sporting and non-sporting activities.

The inclusions in this group may vary from country to country; in the UK it would include walking. The third ring from the centre represents activities that are non-physical but are competitive, organised and commonly regarded as sports; in the UK it would include darts and snooker. The white outer area represents activities that are clearly regarded as non-sport in all countries.

The economic characteristics of sport: sport as a commodity

Sport can provide both psychic and physical benefits to participants. Psychic benefits can arise from the sense of well-being derived from being physically fit and healthy, the mental stimulation and satisfaction obtained from active recreation, and the greater status achieved in peer groups. Physical benefits may relate directly to the health relationship with active recreation. Physical exercise, it is argued, is a direct, positive input into the health production function. There is some evidence to indicate that those who regularly engage in physical exercise are likely to live longer, have higher productivity over their working lives, and have greater life satisfaction and an improved quality of life. We will consider these arguments and the related evidence in later chapters. For the moment, it is us...