eBook - ePub

The Routledge Atlas of Central Eurasian Affairs

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Routledge Atlas of Central Eurasian Affairs

About this book

Providing concisely written entries on the most important current issues in Central Asia and Eurasia, this atlas offers relevant background information on the region's place in the contemporary political and economic world.

Features include:

- Profiles of the constituent countries of Central Asia, namely Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan

- Profiles of Mongolia, western China, Tibet, and the three Caucasus states of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia

- Timely and significant original maps and data for each entry

- A comprehensive glossary, places index and subject index of major concepts, terms and regional issues

- Bibliography and useful websites section

Designed for use in teaching undergraduate and graduate classes and seminars in geography, history, economics, anthropology, international relations, political science and the environment as well as regional courses on the Former Soviet Union, Central Asia, and Eurasia, this atlas is also a comprehensive reference source for libraries and scholars interested in these fields.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

The label and definition of Eurasia has long been used by a wide variety of scholars in the humanities and social sciences. It is generally defined as the expanse of territory that extends from western Russia eastward to the Pacific Ocean and south to include most of China and what is today considered Central Asia and also the Caucasus. Excluded from this broad definition are the Indian subcontinent, Iran and countries in southwest Asia. While there is general agreement on the Eurasian label and territorial definition, there is much less agreement on what is considered Central Eurasia, the regional definition used for this atlas. During the time of the Soviet Union, that label would and could easily have been used to define the five Central Asian Soviet republics or “stans.” In a post-Soviet world, the territorial extent of what is considered Central Eurasia is somewhat a matter of individual scholarly tastes and also sensitivity to using a Soviet territorial label, namely Central Asia. The controversy extends to discussions among scholars about exactly how far “west” a region called Central Eurasia would reach, and also how far “east,” especially with the awakening of China in the global marketplace, global entrepreneurial space and global geopolitical dialogues. Questions about the eastern extent need to weigh which, if any, provinces of western China might legitimately be included in Central Eurasia and also whether Mongolia should. Questions also arise about the western extent of a Central Eurasian region. The inclusion of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia within Europe has posed a dilemma to more than one European geographer and historian; the same dilemmas arise for the Asian scholar.

We are acutely aware of the controversies among geographers, historians, cultural anthropologists, regional economists and Soviet and post-Soviet political scientists regarding decisions as to whether Caucasus states, Mongolia or China’s western provinces legitimately merit inclusion in a Central Eurasian region. While we recognize the merits, the geography community is probably more concerned about territorial boundaries than are other scholars. That is because we seek to identify those cultural, economic, historical and environmental features that have some overriding similarities or homogeneity. More than one introductory world regional geography textbook or regional text on Europe or the Soviet Union, or now Russia, has discussed the perplexities and difficulties that arise in defining Eurasia or even Central Asia. A perusal of maps in the aforementioned books would attest to the different regional boundaries, especially the western and eastern extents.

Our decision was to include a broad expanse of states and territorial units that best define Central Eurasia. In our initial discussions we had no difficulty agreeing that the five Central Asian former Soviet republics, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzia (now Kyrgyzstan), Tajikistan, Turkmenia (now Turkmenistan) and Uzbekistan, would be included in Central Asia. There was also little disagreement that Mongolia merited inclusion. There was some discussion regarding Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, as their cultural, historical and environmental geographies were different from those of the Central Asian “stans.” However, on balance, it was agreed that they should be included in any Central Eurasian region. Questions also arose about China’s three western provinces, Xinjiang, Tibet and Qinghai. Again, on balance, these three administrative units share much more in common culturally with Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan than with Han Chinese regions farther east. Thus, they were included.

What is apparent to scholarly communities studying Central Eurasia is that this region has blossomed into a major arena of disciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary scholarship since the end of the Soviet Union in 1991. The number of books, chapters and journal articles on this region has truly skyrocketed with contributions both by scholars residing in Central Eurasia today, and especially by those from outside the region. Here we are referring to the listservs on Central Asia, such as CentAsia Listserv, but also websites about countries, university degree programs and conferences, and opportunities for language training, fieldwork and research collaboration. The number of scholars with homes in European, Asian and North American universities is significant. These include not only young scholars focusing their careers on one or more research topics or themes, such as religion, politics or gender issues, but also senior scholars who developed a research interest in Central Eurasia following the end of the Cold War and the increase in opportunities for Central Asian language training, interdisciplinary teaching and fieldwork, and conference organizing and presentations. The intellectual and scholarly renaissance of the past twenty years certainly, in our minds, is significant for what has been accomplished. (This topic in itself would be a most interesting and rewarding thesis or dissertation topic, namely who contributed what and when.)

The plethora of research materials published in the past couple of decades is significant, not only in the volume of what has been produced, but in the variety and quality as well. There are now regular sessions at disciplinary and transdisciplinary national and international conferences on historical and current events, developments and processes in Central Eurasia or subregions, such as the Caucasus or Central Asia, or about individual cities, industrial and tourist regions. Added to this mix of scholarly materials we note, in particular, Bregel’s An Historical Atlas of Central Asia. Also a number of atlases have appeared which are devoted to specific periods or specific regions. These include Abazov’s The Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of Central Asia, and the recent Asian Development Bank’s Central Asia Atlas of Natural Resources. Many atlases of Russia also cover the Central Asian states including Brawer’s Atlas of Russia and the Independent Republics, Gilbert’s The Routledge Atlas of Russian History and Milner-Gulland’s Cultural Atlas of Russia and the Former Soviet Union. Atlases about China fill in the picture for western China including National Geographic’s Atlas of China, Benewick and Donald’s The State of China Atlas, and Chinese Academy of Sciences’ The Atlas of Population, Environment and Sustainable Development of China.

While on reflection there are a number of atlases that will aid the regional specialists and regional generalists, no standard comprehensive atlas of Central Eurasia exists that would aid both the highly specialized professional and the new aspiring scholarly communities. In short, the materials about historical, economic, social, political, cultural and environmental matters are at best uneven, with some regions and topics well covered by existing books and atlases, and other parts of Central Eurasia less well represented. It is thus the major purpose of this atlas to include maps on a wide variety of themes for all countries in our Central Eurasian region, from the Caucasus to Central Asia to Mongolia and China’s three western provinces.

In making decisions on what topics to include in this atlas we looked at existing atlases and other sources for ideas we considered important in presenting topics about contemporary, not historical, Central Eurasia. We also decided to include maps on some topics not considered in existing sources that we believed were important in illustrating current economic, cultural, social, environmental and political problems and issues. For example, some historical maps were important, as they are important background materials to understand the present state of Central Eurasia. Other topics are “first time” topics in regional atlases, such as Internet cafés, gender index, environmental crises and geopolitical futures.

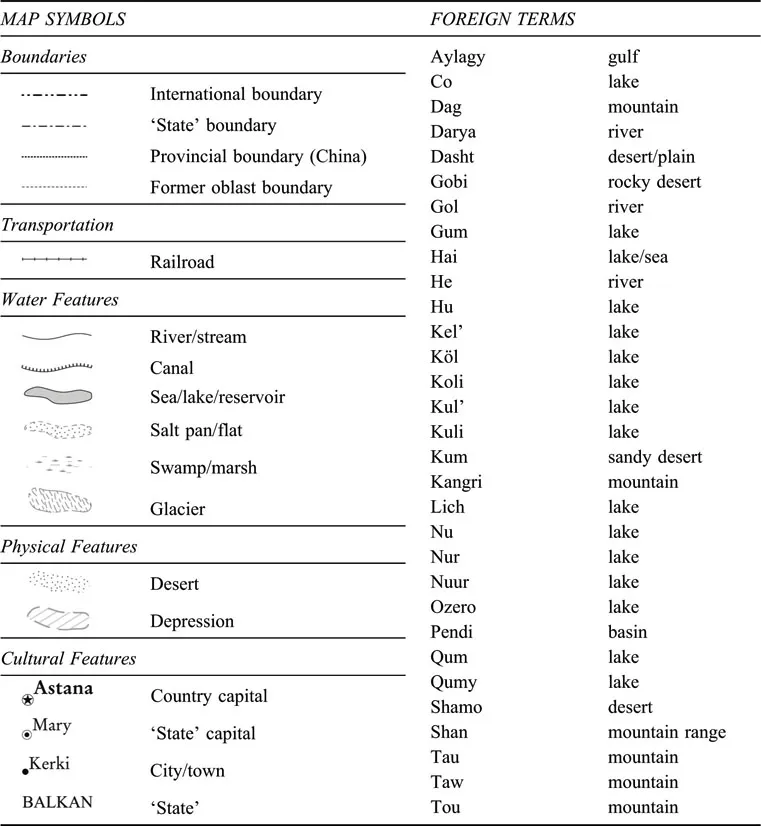

Following this brief introduction, the atlas continues with seven chapters (Chapters 2–8) entitled “General reference,” “Historical,” “Population,” “Environment,” “Economic,” “Cultural” and “Political,” each of which includes five to twelve maps about one or more facets of each topic. Chapter 9, entitled “Countries and provinces,” presents basic historical, cultural, economic and political information; some of this is background information one would find in other sources, but we considered it important to material in this section. A base map of each country or Chinese province is included, as is a population pyramid. is called “Central Eurasian scenarios”; it presents ten scenarios of what Central Eurasia might look like in the next fifty years. Added to the descriptions are six hypothetical maps of political realignment in the region, cartographies that are almost certain to stimulate some healthy scholarly debate and discussion. Finally, in the Bibliography, we list general and specific books, chapters and atlases that one might use to access further information about the region. A number of websites are included; many were used to construct maps for this atlas. The map symbols and language terms used throughout the atlas are shown in Table 1.

We believe this atlas of Central Eurasia serves four main purposes. First, it contains a greater variety and number of maps and graphics (more than a hundred) than any other current atlas. It is thus an important and unique addition to the scholarly literatures. Second, we envision its use in disciplinary and interdisciplinary classes and seminars focusing on Central Eurasia as well as workshops by governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector. These learning sessions might focus on one set of maps, for example, those on environmental issues, economic development or social well-being. Third, it will be a most useful source for scholars ferreting out research topics for theses or dissertations in the humanities and also the social, policy and environmental sciences. In our view, behind each map and map pattern is a series of questions through which one might inquire about both temporal and spatial processes that are worth unraveling through archival research and fieldwork. Fourth, the atlas will be a useful reference source for those working in libraries where reference questions about Central Eurasia will only increase in the coming years.

In our minds, Central Eurasia is a region that is becoming more important and increasingly recognized as an important geoeconomic, geopolitical, geocultural and geoenvironmental region. This “coming of age,” as noted above, is very apparent in disciplinary and inter-disciplinary scholarly circles. It is also, to be sure, being recognized as crucial in European and Asian geoeconomic and geopolitical decisions by corporations, organizations and governments. For these groups and others, it is important to have a specialized atlas available that includes maps of many of the issues important to present and future generations of scholars, NGOs, governments and corporations.

Table 1 Map symbols and foreign terms

2 General reference

Geographic grid

Scholars debate the geographical extent of the region studied in this atlas and also the term to best describe it. Eurasia could be considered as that large land mass that includes all territory east of the Urals, all the way to the northwest Pacific Ocean. Or it could encompass only the five countries in Central Asia: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. This atlas includes these five states in Middle or Central Asia, but also the three states, all former Soviet republics, in the Caucasus, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, which many scholars writing about historical or contemporary events consider to have more in common culturally and politically with the Central Asian states than with Europe. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that there remains a certain amount of ambiguity regarding the accepted territorial limits of what we term Central Eurasia.

The ambiguity in defining the western extent of Central Eurasia also occurs when attempting to establish an eastern boundary. In particular, questions surface over whether it is prudent to use the boundaries of existing states as the best way to delimit this region. If one uses only state and international political boundaries, one would probably exclude Mongolia and also the three westernmost provincial-level units of China, namely Tibet, Xinjiang and Qinghai. However, a very legitimate case can be made for including these units in Central Eurasia as their history and culture are tied closely to those of the five Central Asian states. Whether in terms of religion, language or cultural influences, the three Chinese administrative regions have more in common with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia than they do with central and eastern China, whose pre- and post-colonial history is in sharp contrast.

Geographic location

This mid-latitude region of 9.3 million km2 (3.6 million square miles) extends across roughly 80 degrees longitude (from 40° E to 120° E) and 30 degrees latitude (from 27° N to 55° N). It is bordered on the west by the small Caucasus state of Georgia, which is on the eastern side of the Black Sea, and on the east by the eastern extreme of Mongolia. Western Georgia lies at a similar latitude to Madagascar in the southern hemisphere and eastern Mongolia is roughly on the same longitude as Perth in Western Australia. Central Eurasia’s northern hemisphere latitude is comparable to northern Florida and its northern extent comparable to Labrador or Alaska’s Pacific coast archipelago. In a southern hemisphere context the area would be similar to a region stretching from South America’s Southern Cone to the southern third of Australia.

Map 1 Central Eurasia’s geographic location

Map 2 Geographic grid

Regions and subregions

The territorial size of Central Eurasia is larger than the conterminous United States and roughly equal to that of the South American continent. If Central Eurasia were a country, it would be the fifth largest overall. It would still only be one-third the size of Russia, but it would be larger than Australia or Brazil. What makes this region distinctive on world maps is its interior location in the large Eurasian land mass. While some would define it as an area extending from the Urals all the way east to the Pacific Ocean, others would consider it a region more like the area we are using in this atlas.

Central Eurasia region

The region as we define it in this atlas includes nine states or countries and three Chinese provinces. The states include three in the Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia), five in Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) plus Mongolia. The provinces in western China, Tibet, Qinghai and Xinjiang, round out the Central Eurasian region. While Armenia, with an area of less than 30,000 km2 (11,580 square miles), and Georgia, at 69,700 km2 (approx. 26,900 square miles), are the smallest countries, the largest are Kazakhstan (approx. 2.7 million km2 or 1 million square miles) and Mongolia (approx. 1.5 million km2 or 604,000 square miles). The Xinjiang Autonomous Region (approx. 1.6 million km2 or 640,000 square miles) is slightly larger than both Mongolia and the Tibet Autonomous Region (1.2 million km2 or 474,162 square miles). All the Central Eurasian states except Mongolia and the three Chinese western provinces would fit into Kazakhstan; in fact, together they would fill only half of Kazakhstan’s territory.

Aside from the vastly different population sizes of states in this region, a topic discussed below, there are two other distinctive features observed on the base map. One is the nature of the international boundaries. Five countries border southern Russia; two of them, Kazakhstan and Mongolia, have lengthy borders with this northern neighbor. China’s border with Russia in Central Eurasia is very narrow, just a small piece of territory separating Kazakhstan and Mongolia. Most of these international border areas are lightly populated, but they are nonetheless very important in the world of contemporary geopolitics and economics. Tw...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Introduction

- 2. General reference

- 3. Historical

- 4. Population

- 5. Environment

- 6. Economic

- 7. Cultural

- 8. Political

- 9. Countries and provinces

- 10. Central Eurasian scenarios

- Bibliography

- Index of places

- Index of proper names and terms

- Index of topics, themes and concepts

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Routledge Atlas of Central Eurasian Affairs by Stanley D. Brunn,Stanley W. Toops,Richard Gilbreath in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.