![]()

![]()

1

Simpler, Better

In the past few decades, strategy has become increasingly sophisticated. If you work for a sizable organization, chances are your company has a marketing strategy (to track and shape consumer tastes), a corporate strategy (to benefit from synergies), a global strategy (to capture worldwide business opportunities), an innovation strategy (to pull ahead of the competition), an intellectual property strategy (to defend the spoils of innovation), a digital strategy (to exploit the internet), a social strategy (to interact with communities online), and a talent strategy (to attract individuals with extraordinary skills). And in each of these domains, talented people work on long lists of urgent initiatives.

Companies are right, of course, to consider all these challenges. Rapid technological change, global competition, supply chain disruptions due to climate change and worldwide health emergencies, as well as ever-evolving consumer tastes, do conspire to upend traditional ways of doing business. As the world’s economies became more integrated, firms needed a global strategy. As technology altered consumer tastes and ways to satisfy them, it was imperative to rethink innovation and marketing. As the cost and utter unfairness of limiting workplace diversity became impossible to ignore, companies needed to find ways to build more inclusive talent pools and career paths. By responding to each of the new challenges, however, we asked ever more of our organizations, had even higher expectations of employees, and required our complex strategies to bring about sheer miracles.

I see evidence of such increased expectations everywhere. They manifest themselves in outstanding products, unbelievable experiences, and “deals of a lifetime”—but also in long working hours, seemingly impossible stretch goals, and harried lives. When I visit companies to do research and write cases, I rarely leave without being impressed by how much people accomplish in short periods of time, often with limited resources. But here is what surprises me most: given the sophistication of firm strategies and the intensity of our work lives, I would expect to see impressive firm profitability at most companies and more-than-generous compensation packages for nearly everyone. I see neither. Take firm profitability: one-fourth of the firms included in the S&P 500 fail to earn long-term returns in excess of their cost of capital. In China, this fraction is even higher, closer to one-third.

Think about it. How can it be that so many companies, their ranks filled with talented and highly engaged employees, have so little to show for so much effort? Why do hard work and sophisticated strategy lead to enduring financial success for some companies but not for others? We have the most educated workforce in human history and incredibly talented corporate leaders. Why does enduring success so often seem elusive? If you’ve ever wondered about these questions, this book is for you.

When our companies fall short of expectations, we often suspect that we are missing some key ingredient. If only we had a better talent strategy. If only we had a more robust supply chain. If only we had a richer innovation pipeline. If only … And so we develop a talent strategy, invest in business resilience, accelerate innovation cycles. As our strategic initiatives multiply, something unforeseen happens. In concentrating on all the trees, we lose sight of the forest. In a profusion of activities, an overall direction, a guiding principle, is hard to see. Any promising idea is an idea that seems worth pursuing. In the end, common sense rules, and strategy loses much of its ability to steer our businesses. In this world, strategic planning becomes an annual ritual that feels bureaucratic and less than helpful in resolving critical issues. In fact, it is not difficult to find firms that have no strategy at all. In many others, it consists of an 80-page deck that is rich in data but short on insights, fabulous at listing considerations but of little help in actual decision-making.1 When I review companies’ strategic plans, I often see a plethora of frameworks—many of them inconsistent with each other—but few guideposts for effective management. If the hallmark of a great strategy is its telling you what not to do, what not to worry about, which developments to disregard, many of today’s efforts fall short.2

In this book, I argue that strategic management faces an attractive back-to-basics opportunity. By simplifying strategy, we can make it more powerful. By using an overarching, easy-to-grasp framework that is tied to financial success, we gain a common language that allows us to evaluate and pull together the many activities that take place in our organizations today.

I have seen the effect of simpler thinking in hundreds of executives I have taught at Harvard Business School. These managers were familiar with popular strategy frameworks, and their firms had often implemented laborious planning processes to guide investment decisions and managerial attention. Yet in many instances, it was difficult, even for these accomplished professionals, to recognize how specific projects were linked to their firm’s strategy. At best, strategy provided smart arguments for and against business propositions, but it offered little guidance on how to choose and where to focus. As a result, initiatives and activities proliferated. When no one knows when to say no, most ideas (brought forward by talented and ambitious employees) seem like good ideas. And when most ideas seem like good ideas, we end up in the hyperactivity that pervades the business world today.3

I honed my approach to strategy in response to the challenges that I observed in the classroom and in my capacity as an adviser to companies. In my experience, value-based strategy, the approach I describe in this book, is well suited to cutting through complexities and evaluating strategic initiatives. The framework provides a powerful tool that will allow you to see how your digital strategy is (or is not) related to your global ambitions, and how your marketing strategy is (or is not) consistent with the way you compete in the market for talent. Value-based strategy helps inform your decisions about where to focus and how to deepen your firm’s competitive advantage.

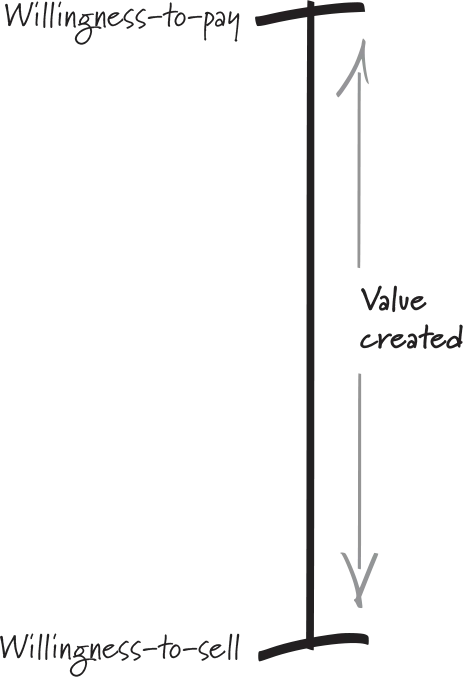

The basic intuition underlying value-based strategy could not be simpler: companies that achieve enduring financial success create substantial value for their customers, their employees, or their suppliers. The idea is best captured in a simple graph, which I call a value stick (figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1 How businesses create value

Willingness-to-pay (WTP) sits at the top end of the value stick. It represents the customer’s point of view. More specifically, it is the most a customer would ever pay for a product or service. If companies find ways to improve their product, WTP will increase.

Willingness-to-sell (WTS), at the bottom end of the value stick, refers to employees and suppliers. For employees, WTS is the minimum compensation they require to accept a job offer. If companies make work more attractive, WTS declines. If a job is particularly dangerous, WTS increases and workers require more compensation.4 In the case of suppliers, WTS is the lowest price at which they are willing to sell products and services. If companies make it easier for their suppliers to produce and ship products, supplier WTS will fall.

The difference between WTP and WTS, the length of the stick, is the value that a firm creates. Research shows that extraordinary financial performance (returns in excess of a firm’s cost of capital) is rooted in greater value creation.5 And there are only two ways to create additional value: increase WTP, or lower WTS.6 Strategy is conceptually simple, and simpler strategic thinking, I am convinced, will lead to better outcomes.

Renew Blue

An example of the power of this approach is Best Buy, America’s biggest consumer electronics and appliances retailer. In late 2012, the company was looking for a new CEO. Imagine yourself taking on this role. It seemed impossible to succeed. Best Buy, most of us thought, was doomed. Amazon had successfully grown its electronics business at the expense of Best Buy, offering consumers a broad selection of products and aggressive pricing. At the same time, Walmart and other big-box retailers stole market share by focusing on the most popular devices and appliances that could be sold at high volumes. Worst, perhaps, was the growing trend among customers to “showroom,” that is, to visit stores to decide which products they liked and then buy them online. Having endured this onslaught, it is no surprise that Best Buy performed poorly. In 2012, the company lost $1.7 billion in a single quarter. Its return on invested capital (ROIC), which had long been in decline but was still in the upper teens, plunged to minus 16.7 percent.7 “It was as if Best Buy was coming to a gunfight with a knife,” said Colin McGranahan, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein. “Best Buy Should Be Dead,” titled Business Insider.

Hubert Joly, a former strategy consultant and most recently CEO of Carlson, a hotel and travel conglomerate, took on the challenge. Recognizing the dire circumstances, Joly and his team devised a plan they dubbed Renew Blue. The core idea was to create more customer value by increasing WTP and improving price perception. Rather than thinking of Best Buy’s more than 1,000 stores as a liability that made it difficult to compete, the company reimagined their role and turned them into assets. Going forward, the stores would serve four functions: points of sale (the traditional role), showrooms for brands that built stores-within-a-store, pickup locations, and mini-warehouses.

Best Buy had allowed Apple to operate its own showrooms in Best Buy stores starting in 2007. Joly expanded the program, adding Samsung Experience Shops and Windows Stores in 2013 and the Sony Experience a year later. Even Amazon eventually opened kiosks in Best Buy stores. The store-within-a-store concept provided the company with a fresh source of revenue and an enhanced shopper experience. Sharon McCollam, then CFO, explained, “When you look at the investments that our vendors have made in our stores, it is incredible. It is literally hundreds of millions of dollars.”8 Vendors also subsidized the salaries of Best Buy employees who worked in their showrooms. Perhaps more importantly, Best Buy was now able to offer deeper sales expertise because the company’s staff, dressed in vendor-branded shirts and supported by consultants, each focused on a specific brand. Not only did the store-within-a-store program benefit Best Buy, the company’s vendors were also better off. By creating a more cost-effective way to reach customers—operating a store-within-a-store is less expensive than running your own store, and vendors can benefit from increased traffic—Best Buy lowered vendors’ operating cost and, as a result, vendors’ WTS.9

Using Best Buy’s stores as mini warehouses proved similarly effective. Joly’s team understood that the speed at which customers received new products was an important driver of their WTP. It is hard to beat instant gratification. Traditionally, the company had shipped from large distribution centers. These were closed on weekends, and the inventory management software was decades old, leading to frequent stockouts and snail-speed shipping.10 Under the Renew Blue plan, products were shipped from the location that provided the quickest delivery— sometimes a distribution center but often a store down the road. By 2013, Best Buy shipped from 400 stores. A year later, that number rose to 1,400, helping the company beat Amazon’s shipping times for the first time.11 Customers also loved the idea of ordering online and picking up the products in Best Buy stores. Within a few years, 40 percent of Best Buy’s online orders were either shipped from or picked up from a store.12

Joly and his team also reasses...