1

Global patterns and perspectives

By the end of this chapter you should:

- be aware of the contribution of geography to the understanding of urban places;

- have a broad appreciation of the meaning and value of global perspectives in understanding the contemporary world;

- have a basic familiarity with the debates which surround the concept of globalisation.

Introduction

The recent millennium was a major watershed in the evolution of human settlement, for it marked the period when the location of the world’s people became more urban than rural. It is likely that the figure of 50 per cent urban was achieved at some point between 1996 and 2001 but it is not possible to be exact because of variations among countries in the quality of their census data and in the ways in which urban areas are defined. Despite its geographical significance, this historical transition went largely unrecognised and unreported, so its profound symbolic importance was overlooked. More of the six billion inhabitants of the globe now live in towns and cities than in villages and hamlets. No longer are towns and cities exceptional settlement forms in predominantly rural societies. The world is an urban place.

Urban development on this scale is a remarkable geographical phenomenon. Far from being spread widely and thinly across the surface of the habitable earth, a population which is urban is one in which vast numbers of people are clustered together in very small areas. Whether through choice or compulsion, they live in close horizontal and vertical proximity and at very high densities. They seemingly prefer, or are forced to accept, concentration rather than dispersal. The benefits of access to services and other people, which are a consequence of closeness and agglomeration, apparently outweigh the disadvantages and drawbacks of crowding, congestion, noise and pollution. If the size of population is any guide, then living in an urban environment has greater appeal than residing in the countryside. The number and size of cities and the rate at which many of them are growing suggests that they are, and are likely to remain, highly attractive and acceptable forms of settlement to most people.

Cities are economic and social systems in space. They are a product of deep-seated and persistent processes which enable and encourage people to amass in large numbers in small areas. Surplus products, generated outside the city, provide the basic means of support, but viability and prosperity also depend on the existence of social arrangements and institutions through which cities are regulated and managed. So powerful and pervasive are the forces of urban formation and growth that they presently concentrate over three billion of the world’s population in towns and cities. It is difficult adequately to convey an impression of the degree of clustering which this represents, as data on the combined area of all the world’s urban places are not readily available. If, however, all the urban population lived at a density of 7,600 per sq. km, which is the average for the major cities of eastern Asia, then they could be accommodated on less than 1 per cent of the world’s landmass, in an area roughly equivalent in size to Germany.

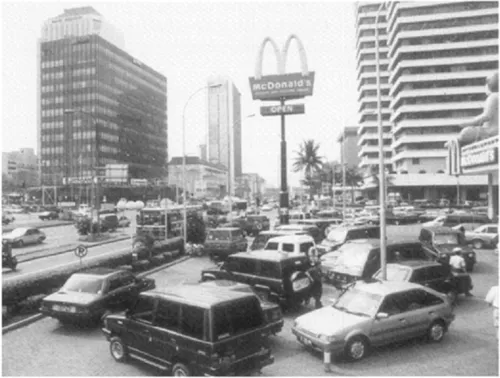

The urban world is distinctive in socio-economic as well as in spatial terms. Despite the infinite and intricate variations of tradition and culture that exist within and between nations, cities appear to have, and to be acquiring, more in common than they have differences. Urban places have many similarities of physical appearance, economic structure and social organisation and are beset by the same problems of employment, housing, health, transport and environmental quality. The elements in many urban skylines are the same, as commercial and residential areas are increasingly dominated by high-rise developments constructed in international styles. Streetscapes across the world are adjusting in the same way to accommodate the needs of the ubiquitous car, so cities are fast losing their individual layouts and architectural identities. Within buildings, workers do the same sorts of jobs, often on the same makes of computer or machine, and manufacture goods and services to the requirements of world markets dominated by a small number of global producers. Patterns of demand are converging as consumerism absorbs ever more of the world’s population. There are few cities where McDonald’s hamburgers (Plate 1.1), Fuji films, Microsoft’s Office and Coca-Cola are not readily available and purchased in quantity. Some of these similarities are superficial and hide important underlying cultural differences, but the underlying trend is clear. There is increasing convergence among cities in physical and economic terms.

Plate 1.1 Icons and images in the global city: a street in Jakarta, Indonesia

Irrespective of continent or country, many urban residents live their lives in broadly similar ways, with common concerns over home, children, school and work. Attitudes and expectations are shared as many aspire towards the lifestyles that are popularised and promoted by the mass media. Billions of people feast nightly on a diet of televised soap operas and international sporting events, with pop singers, film stars, sports personalities and media celebrities enjoying a worldwide recognition and following. Identification is reflected in fashions and accessories, with designer brands and labels such as Adidas, Tommy Hilfiger, Calvin Klein, Levi, Nike and Nokia commanding widespread following. Such interests, fads and tastes are increasingly independent of ethnicity, colour, class and creed. They draw together and fuse what geography and culture traditionally separate and divide. The contemporary urban world is more than a motley assemblage of diverse settlements. Many observers argue that it is slowly becoming a unitary and uniform place, a global city in which most of its inhabitants are imbued with a similar set of all-encompassing urban attitudes and values and follow common modes of behaviour.

Although towns and cities have existed for over eight millennia, the wholesale transition to urban location and urban living is very recent in origin. Many highly successful urban civilisations existed in the past, but their impacts were both limited and localised. In 1700 fewer than 2 per cent of the world’s population lived in urban places and these were concentrated in a small number of city states. Major and rapid changes began in Britain in the late eighteenth century in response to the locational dictates of industrial capitalism. They subsequently spread to north-western Europe and north-eastern USA so that, by the beginning of the twentieth century, about 15 per cent of the world’s population was living in urban places. Urban development as a global phenomenon is, however, essentially a feature of the last half of the twentieth century, indeed of its last three decades. Large parts of the world were effectively untouched by urban development and urban influences until 1970. They are occurring today because of massive changes in the distribution of population in countries which, until recently, were substantially and profoundly rural. Contemporary processes of urban development affect vast numbers of people across the globe. Although it is taking place at a local level, the present switch from rural to urban constitutes the largest shift in the location of population ever recorded.

Historical milestones are occasions for reflection and speculation; for looking back and to the future. They are a time for assessing what has been achieved and what opportunities, obstacles and likely outcomes lie ahead. The emergence of an urban world and the prospects for a global city pose important questions concerning the nature and consequences of the urban pattern and experience. They focus attention upon the reasons how and why cities exist, the ways in which they grow and their impact upon society. They raise issues concerning spatial and temporal variations in levels and rates of urban development and the implications of future urban change. Serious reservations surround the environmental and social sustainability of urban populations as the number and size of cities continue to increase. Such concerns challenge analysts to develop appropriate philosophies and methodologies by means of which the urban world can be conceptualised, explained and understood.

Studying the urban world

In view of this ambitious research agenda, it is not surprising to find that the task of analysis and explanation occupies an army of specialists drawn from a wide range of fields in the social and environmental sciences. No one discipline can claim to monopolise the study of the city, since urban questions and problems cut across many of the traditional divisions of academic inquiry. Equally, no single methodology predominates in urban analysis, for the complexities of urban life necessitate the adoption of a wide variety of approaches. It is in the interdisciplinary nature of urban issues that the city poses the greatest intellectual challenge to the analyst. Progress in urban study requires the fusion of insights derived from a number of subject areas, each of which approaches the analysis of urban settlements in its own distinctive way.

Geographers are prominent among the researchers who set out to analyse and explain the urban world and the global city. In focusing upon location they seek to add a spatial dimension to the understanding and interpretation of global urban phenomena (Box 1.1). Geographers are

BOX 1.1

THE NATURE OF GEOGRAPHICAL STUDY

Geography is the academic discipline that explores the relationship between the Earth and its peoples through the study of place, space and the environment.

The study of place seeks to describe, explain and understand the location of the human and physical features of the Earth and the processes, systems and interrelationships that create or influence those features.

The study of space seeks to explore the relationships between places and patterns of activity from the use people make of the physical settings in which they live and work.

The study of environment embraces both its human and physical dimensions. It addresses the resources that the Earth provides, the impact upon those resources of human activities, and the wider economic, political and cultural consequences of the interrelationship between the two.

The spatial perspective upon phenomena that is adopted in geography is distinctive, even though geographers may look at the same phenomenon as other specialists. No other discipline has location and distribution as its major focus of study.

Source: DES and the Welsh Office (1990:6).

concerned to identify and account for the distribution and growth of towns and cities and the spatial similarities and contrasts that exist within and between them. They focus on both the contemporary urban pattern and the ways in which the distribution and internal arrangement of settlements have changed over time. They look at the ways in which cities are represented as places through appearances and images, how people identify with them and the effects upon ways of life and behaviour. Emphasis in urban geography is directed towards the understanding of those social and economic processes that determine the existence, evolution and functional organisation of urban places and the characteristics of urban society. In this way, geographical analysis both supplements and complements the insights provided by allied disciplines in the social sciences that recognise the urban world as a distinctive focus of study.

A wide range of approaches and methods is used by geographers in urban study (Box 1.2). Simple mapping of distributions is the starting point for most geographical work, since it identifies basic patterns and draws attention to possible causal relationships. It is especially appropriate at the global scale, where it is important to start with an overall picture and where variations, and hence the implications of urban development, are both complex and pronounced. Mapping, however, leads to little more than low-level description and is undermined by the highly variable quality of global urban data (see Appendix). Explanation is facilitated if attention is concentrated upon causal actions and mechanisms. Such relationships are products of tradition, culture and politics and are deeply embedded in the underlying strata that give societies and economies their form. A key task for geographers is to investigate and to understand the structural relationships that give rise to processes that in turn are responsible for creating observed urban patterns.

Although an urban specialism is long established in geography, the adoption of a world perspective on cities and urban society is a recent development. It was foreshadowed nearly 100 years ago in the formative work of Adna Ferin Weber (1899) on The Growth of Cities in the Nineteenth Century, although the urban ‘world’ that he analysed consisted of only around 50 countries in which there was significant urban development. This major empirical study was important because it showed how much earlier and further advanced were England, Wales and Scotland as urban societies and how little urban development there was outside north-western Europe and the eastern seaboard of the USA. The world at the time was very much a rural place in which the development and distribution of towns and cities was limited and urban influences were restricted and localised.

BOX 1.2

PHILOSOPHICAL PERSPECTIVES IN URBAN GEOGRAPHICAL STUDY

Geographers approach the study of urban worlds and global cities from a number of philosophical perspectives that contribute to explanation and understanding in different ways, Several are reflected in different sections of this book:

Positivism is the principle that underlies ‘scientific’ human geography. It assumes that there is regularity and uniformity in the distribution and characteristics of cities that can be observed, analysed and explained by an independent analyst. Positivist approaches seek to develop general rather than unique explanations. These are typically advanced in the form of models, theories and hypotheses of urban location. A major criticism is that observations are inherently subjective because analysts cannot stand outside society and distance themselves from it,

Behavioural approaches seek to explain urban patterns by focusing upon processes of decision-making. The emphasis is upon how people perceive the world and so behave towards it. The approach is of greatest value in micro-scale urban studies of, for example, shopping and migration. Perception, behaviour and decision-making are difficult to measure and to observe objectively. Individual differences tend to become blurred and so of limited importance in studies at aggregate scales.

Structuralism involves a belief that geographical patterns are grounded in underlying formations such as capitalism, rather than in superficial concepts like price, rent and profit. They may be products of power relationships that are studied by adherents of a political economy approach. Links between underlying structure and surface pattern, however, are difficult to disentangle, as they operate indirectly. Another criticism is that analysts following this approach are themselves products of the underlying structure and can only ever view patterns from the inside.

Proponents of postmodern approaches reject the idea of grand theory and emphasise instead the importance of differences, identities and representations. These may be reflected in buildings, iconography and signs. The prime concern is to try to understand the urban world from the multiple viewpoints of diverse individuals and groups. It is difficult, however, to capture the fall range of differences in diverse populations. A further problem is to produce insights of general value and relevance out of understandings of the unique.

Within urbanised countries, statistics on employment patterns, family structures and demography pointed to the existence of pronounced urban-rural contrasts. Cities were places with particular socio-economic characters that sustained and perpetuated distinctive patterns of social and economic behaviour. They were places in which urban ways of life evolved and were spread into the surrounding rural areas. As well as identifying the salient characteristics of the urban world, Weber’s analysis was of considerable significance in a technical sense, since it drew attention to the many problems of data availability, quality and comparability that so bedevil urban analysis and understanding at the global scale.

The principal focus of subsequent work in urban geography was on systematic themes rather than overall global patterns. Important contributions were made to the understanding of urban lifestyles (Wirth, 1938), city size distributions (Zipf, 1949; Berry, 1961), urbanisation (Davis, 1965) and the colonial city (McGee, 1967), establishing traditions of research in these areas, but these studies directed attent...