![]()

Media law is a very broad body of law that incorporates elements of copyright and trademark law, contract law, labor law, defamation and privacy law, telecommunications law and policy, and the many legal issues that arise from the First Amendment's guarantees of free speech and freedom of the press.

To protect themselves from lawsuits and other legal entanglements, media producers need to be familiar with these key areas of law. Just as important, media professionals must be able to recognize the various guises under which legal issues can appear during the production process. Consider this fictional account of the legal roadblocks that confronted one unwary producer:

Richard Newman is the director of production in the corporate media department of a large financial firm. At the request of the firm's training division, Newman produced a 45-minute program on management communication skills titled Listen While You Work. Newman assumed that, like all of the other programs he had produced for the firm, Listen While You Work would be limited to distribution within the company.

In producing the program, Newman faced a familiar battle. He wanted to create an engaging, effective training program, but he was constrained by a limited production budget and tight schedule. As a result, Newman found himself borrowing material from a variety of sources. To illustrate the effects of poor communication, for example, he used footage from a vintage theatrical film he had rented from his neighborhood video store. To add some punch to the audio track, he inserted clips from several popular rock-and-roll recordings.

Newman shot most of the original video material in the company's headquarters, using employees as his “talent.” Newman also wrote the script, with some help from a friend who is a professional writer. The script included dialogue adapted from several case studies published in a popular management text, plus material taken from videotaped interviews with management consultants. Portions of the script were performed by an announcer Newman hired on a flat-fee basis.

With deadlines pressing, and assuming that Listen While You Work would be limited to internal use at his company, Newman did not bother to negotiate formal contracts with the scriptwriter or announcer. He also did not bother to ask for signed releases from the employees who appeared in the program or the management consultants who had participated in the videotaped interviews.

Newman put a great deal of his own time into the production, completing the final edits himself on the weekend before the program was scheduled to premiere at the company's annual management training conference. His hard work paid off. The program played to a packed house and received rave reviews from company management.

The production also received something that Newman had not expected—an offer to distribute the program outside the company. The offer came from the company's marketing department, which was looking into new ways to generate revenues from the firm's internal resources.

Although Newman was flattered by the offer, he realized that his haste in producing the program might have left some legal strings untied. A call to the corporate legal office confirmed that many questions needed to be resolved before the production could be cleared for external distribution. Faced with the prospect of having to wait for answers to those questions, the marketing department withdrew its offer to distribute the program.

Newman was wise to contact his corporate legal department, but it does not take a trained legal mind to recognize many of the matters that were cause for concern. A partial list follows:

• | Use of copyrighted footage from a motion picture without seeking permission from the individual, group, or organization that owns or controls the film's copyright |

• | Use of copyrighted music recordings on the soundtrack without obtaining clearances from the songwriters or music publishers and record companies |

• | Use of copyrighted excerpts from a book without obtaining permission from the book's author or publisher |

• | Failure to secure releases from employees featured in the production. Because of this oversight, employees who may feel that the program depicts them in an unfavorable light might be able to sue Newman or the company for which Newman works for invasion of privacy or defamation. Employees featured in the production also could sue to collect a portion of the revenues that the program generates through outside distribution. |

• | Failure to secure written contracts or release forms from the scriptwriter and announcer who worked on the program. Although the scriptwriter and announcer apparently agreed to participate on a flat-fee basis that would not provide them with any ownership or residual interest in the program, they might change their minds now that the program has the potential to generate revenues through outside sales. With no written releases or contracts, Newman would have no tangible evidence to support his contention that the pair agreed to provide their services on a flat-fee basis and that they assigned all rights in their work to his company. |

• | Violation of guild agreements. If the scriptwriter and announcer were members of a union or guild, Newman and his company also might find themselves in trouble for not complying with the terms of guild agreements. As discussed in Chapter 7, however, this would not be the case if Newman's company was not a signatory to the relevant guild agreements. In that case, the writer and announcer themselves could face sanctions from their own guilds. |

Newman's case also raises another key issue. Who would actually own Listen While You Work, Newman or his company? Under U.S. copyright law, the company would have the most legitimate claim to ownership of the finished production, unless Newman's employment contract stated otherwise. This would be the case because Newman produced the program within the normal scope of his employment—even though he spent some of his own time on the project. To avoid disputes over the ownership of materials produced on the job, many companies require employees to sign release forms as part of their employment agreement.

One final issue is worth addressing. Would Newman have been free of these legal concerns if, as he had originally assumed, Listen While You Work had been limited to internal distribution? As discussed in subsequent chapters, the answer to that question is no, even though limiting distribution of the program certainly would have reduced his exposure and the risk of litigation.

How Much Law Do You Need to Know?

Although the Listen While You Work scenario was stretched to make a point, it does raise some of the very real legal troubles and concerns that can afflict unwary producers. This is not to suggest, though, that producers should become paranoid, paralyzed by fears that any action they take will leave them open to lawsuits or other litigation. Instead, producers should seek the creative freedom that comes from understanding when it is necessary to take specific steps and precautions to protect their work. Leave the heavy worrying and the paranoia to the lawyers.

Above all, as a media professional, a producer does not need to be a lawyer. A producer does not need to know, for example, how to draft legal documents, how to conduct and analyze a copyright or trademark search, or how to defend a case in court. As the individual with primary responsibility for a media production, however, a producer should know the following:

• | When it would be prudent for the parties in a production deal to sign legally binding agreements |

• | What permissions, permits, and releases are required during the course of a production |

• | When it is permissible to incorporate copyrighted materials in a production without the copyright owner's authorization |

• | What special steps are necessary to add music to a production |

• | What legal issues are involved in working with, and working without, guild and union members |

• | What statements or portrayals in a video production may constitute libel, an invasion of privacy, or a violation of the right-of-publicity |

• | What special precautions are recommended in connection with productions that will be used to advertise a product or service or programs that will be broadcast, cablecast, or transmitted over the Internet |

• | How copyright and trademark registration can help protect finished productions |

This book examines how these and other legal issues can arise during media production and how producers can take steps to address these issues in a manner that protects both them and their media properties. First, though, it helps to understand just who creates, interprets, and enforces media law.

Who Creates Media Law?

According to most high school social studies texts, laws are created in a fairly straightforward manner. At the federal level, the Congress, responding to a public need, drafts and then passes a piece of legislation or bill. Congress next sends the bill to the president, who either signs or vetoes it. Once the president signs the legislation, or once Congress overrides a veto by the president, responsibility for interpreting and applying the newly enacted law falls to the federal courts. If the law is challenged on constitutional grounds, the federal courts also are responsible for determining whether the new law conflicts with the U.S. Constitution, the venerable document that establishes the scope and structure of the federal government and that defines and delineates federal lawmaking powers.

The textbooks provide a parallel model for lawmaking at the state level. According to this model, state laws are created when state legislatures draft and pass legislation and the governor signs or vetoes the bill. Once the governor signs the legislation or once the state legislature overrides a veto by the governor, the courts in that state are responsible for interpreting and applying the law.

Although these textbook models are essentially accurate, they do not tell the whole story. In drafting legislation, for example, Congress and individual state legislatures often are responding as much to private and political pressure as to public need. Private lobbying groups, including many groups representing media interests, work overtime to promote or prevent the passage of legislation that affects their industries. Similarly, various public interest groups may lobby for or against particular legislation based on its potential impact on the interests and positions that these groups represent. In addition, before most bills are voted on by the full Senate and House of Representatives or by the comparable state legislative bodies, the bills must make their way through a gauntlet of committee meetings and hearings.

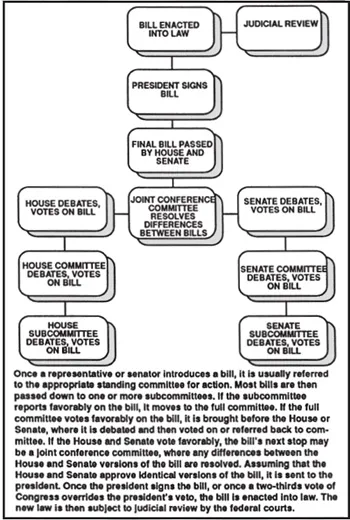

Figure 1.1 illustrates, in a very general way, the process through which a bill becomes law at the federal level. Although this process may help ensure that all evidence for and against a bill is heard, it also opens almost limitless opportunities for backstage deals and political trade-offs. The result is often a piece of legislation that resembles a patchwork quilt of conflicting aims and interests rather than a clear, coherent law.

Figure 1.1 An overview of how federal laws are made.

The Role of the Courts

Civics texts and conventional wisdom also tend to simplify the role of the courts in the lawmaking process. Most texts describe a primarily reactive, interpretive role for the judiciary in the lawmaking and governing process. In truth, however, the federal and state courts often play an active role in shaping both the scope and impact of statutes enacted by the lawmaking branches of government. This is especially true for the U.S. Supreme Court and the federal appeals courts, whose rulings serve as legal precedents that lower federal courts (and, in matters involving constitutional questions, state courts) are obliged to follow. In fact, these higher court rulings often have the effect of law, particularly in areas where legislative statutes are vague or incomplete. This “judge-made” law is discussed more fully in the section on types and categories of law that follows.

The Role of Regulatory and Administrative Agencies

Another fact that many texts tend to downplay is the power that regulatory and administrative agencies exercise in creating and applying laws. Acting under legislative authority, government agencies and commissions create regulations and rules that, in most respects, have the same force and effect as formally enacted laws. This would come as quite a surprise to the framers of the U.S. Constitution, who never defined a formal role for federal bureaucracies in the system of checks and balances that is supposed to govern lawmaking.

State and Local Governments

As suggested previously, state and local governments add more layers of complexity to the lawmaking process. Every state has its own executive, legislative, and judicial branches of governmen...