Public Private Partnerships in Construction

Duncan Cartlidge

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Public Private Partnerships in Construction

Duncan Cartlidge

About This Book

Collaborative working and partnering between the public and private sectors has been fairly standard practice in some form or other for over 100 years, but it is only in recent years that it has become more prevalent. In the UK, it is little more thanten years since the most widely known Public Private Partnership (PPP), the Private Finance Initiative (PFI), was launched and yet it has already been described by some as 'the new economic paradigm.'

Public Private Partnerships in Construction is an authoritative and objective source of information on PPPs, including lessons to be learnt from the past decade, as well as coverage of their spread beyond the UK to governments in areasas diverse as Cambodia and California.

With its detailed presentation ofcurrent issues, illustrated with case studies, this book provides a valuable practical resource for a range of students and professionals.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Chapter 1

The PPP phenomenon

In April 2004, The European Commission issued a green paper entitled On Public–Private Partnerships and Community Law on Public Contracts and Concessions in which Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) were referred to as ‘a phenomenon’. Alternative definitions of phenomenon are ‘marvel’ and ‘miracle’, which one suspects was not quite what the Commission had in mind when searching for a term to describe the spread of this form of procurement. Rather it is a case of ‘bewilderment’, ‘panic’ and ‘confusion’ on the part of the Commission at the rapid growth of PPPs in Europe, which currently operate in a state of EU regulatory limbo.

- All individuals share the risks and rewards of the business.

- Each partner is entitled to share the net profits of the business. A contract need not provide for equal shares which may depend upon how much the partner has invested.

- Partners are jointly and severally responsible for all the debts and obligations of the business without any limit, including loss and damages arising from wrongful acts or omissions of their fellow partners and potential liability to third parties.

- Partners have equal rights to make decisions which affect the business or the business assets.

- All individuals share the ownership of the assets of the business, although they may have agreed that the firm will use an asset which is bought by one of the partners individually.

PPPs cannot then be said to be partnerships in the generally accepted definition of the term and indeed the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) defined PPPs as ‘a risk sharing relationship based on an agreed aspiration between the public and the private sectors to bring about a public policy outcome.’ Nevertheless the focus of partnerships and partnering in construction has developed a significant profile in the United Kingdom during the past ten years. It was the subject of a series of reports in the early 1990s and then further impetus came from the publication of Sir Michael Latham’s report Constructing the Team in 1994 and Sir John Egan’s Rethinking Construction in 1998 where strong emphasis was placed on long-term partnering agreements between the supply and demand sides of the construction industry. Although the distinction should be made between partnerships and partnering, the lines sometimes become blurred and several of the PPPs described later in this book, NHS ProCure21 for example, are very firmly based on Latham’s and Egan’s partnering principles. More than a decade after the Latham Report there are many within the construction industry who believe that a ‘them and us’ culture is still strong when it comes to procurement. Despite the best efforts of Latham and Egan and a whole series of government-led initiatives to improve efficiency in 2005 a National Audit Office (NAO) report, Improving Public Services through better construction, claimed that £2.6 billion a year is still wasted because of the poor management of public sector construction projects in the United Kingdom.

The great debate

Whilst this book attempts to steer a course away from being a political polemic on the ethics of PPPs it is not possible to totally ignore the many public debates that have raged and continue to rage on this approach to public procurement. To some within the public sector, the concept of a PPP, in which the private sector is given a long-term licence to deliver public sector services for profit, is an anathema and over the ten years or so from its first introduction the debate continues about the ethics and suitability of this method of asset procurement. In the various debates one fact, is often overlooked namely that PPPs are primarily a method of procurement; however, to some they have also been seen as

- a method to raise finance off balance sheet – see Chapter 3;

- a strategy to achieve greater efficiency;

- a politically motivated tool to engine social change.

One of the most outspoken critics on PPPs has been the trade union UNISON which shortly after the introduction of PPPs launched its Positively Public Campaign in order to ‘keep public services public.’ According to UNISON the reasons why the PFI (Private Finance Initiative), for example, should be opposed are because of the following:

- The death of the public sector ethos with the introduction of private sector contractors.

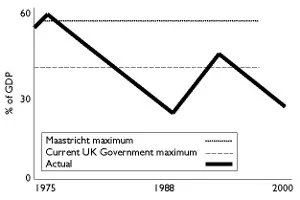

- The PFI is driven by a political motive to control public spending rather than to deliver better public services see Figure 1.1.

- PFI schemes actually cost more than conventionally procured assets due to a range of factors including higher finance costs and high fees for professional advisors, etc.

- PFI consortia profit from employing their workforce on inferior terms and conditions to those in the public sector and in some cases this has resulted in a two-tier work force within the same organisation.

- There is no evidence to support the claim that the private sector can deliver public service outcomes more effectively than the public sector and in fact many privately operated projects are underperforming.

Figure 1.1 Public sector net debt as a percentage of GDP.

Figure 1.1 Public sector net debt as a percentage of GDP.

Source: HM Treasury. - Similarly, it has been suggested that the added value brought about through risks being transferred from the public to the private sector is nothing more than ‘pseudo-scientific mumbo jumbo where financial modeling takes over from thinking’.

- Private sector companies make unacceptably high profits from PPPs and in particular the practice of refinancing PFI deals at an early stage in the project’s life has been heavily criticised.

- Many PPPs reduce the traditional accountability of public sector projects under the cloak of commercial sensitivity.

- design

- construction

- finance (which may be a mixture of public and private sources)

- facilities management

- service delivery ...