![]()

1

Construction Procurement – the Case for a New Way

In no other important industry is the responsibility for the

design so far removed from the responsibilities of production.

—Sir Harold Emerson 1964

Introduction

The ability successfully to procure built assets is at the heart of the construction process and in turn at the heart of the procurement process is identifying the constantly evolving needs of the construction client.

Just what Every Construction Client Wants!

What are the drivers of construction procurement in the UK and are they so much different to other sectors? If one were to ask some of the 2.5 million customers in the UK who annually buy a new car – what were the criteria for buying a particular model? – the answers would probably be:

• long warranties, reliability, no defects;

• fitness for purpose, that is, 4 × 4, family saloon, etc.;

• features, such as air conditioning, CD player included as standard;

• long service intervals and low running and maintenance costs;

• delivered promptly.

In fact criteria that all in all, add up to perceived value for money over the life span of the vehicle. Criteria that appear to be recognized and taken into consideration by the automotive industry, as the following quote from BMW’s marketing information illustrates:

The true cost of the vehicles on your fleet is a balanced measure of all the relevant attributable costs. Servicing, on-the-road price, depreciation and days off road are all essential measures that will directly affect your fleet budget. With high residual values, lengthy servicing intervals and excellent build quality, the BMW and MINI range are well placed to offer some significant advan-tages over competitive marques … with the Whole Life Costs of the BMW and MINI ranges you will be pleasantly surprised to find that it makes financial sense to offer our cars to your company car drivers as part of your fleet.

Admittedly the life span of a family car is not as long as the average new construction project, but if only procuring built assets sounded so simple. As illustrated in Figure 1.1 not only do construction clients traditionally have to grapple with a whole range of diverse issues, but in addition with a diverse range of professional and technical advice.

Figure 1.1 The construction client’s dilemma.

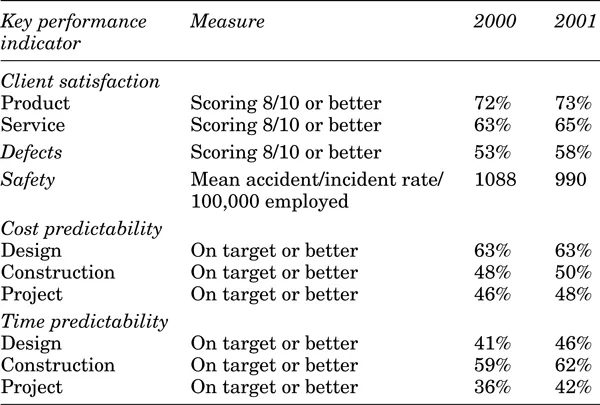

Similarly, if British Airways were to consider replacing its ageing transatlantic fleet of Boeing 747 jets, the criteria for choosing the most appropriate aircraft would probably be similar to those of the car buyer. By way of contrast, Table 1.1 taken from the dti 2002 annual construction industry performance indicates that 10 years post-Latham the UK construction industry is still failing to meet the expectations of its clients. How many car buyers, for example, would be prepared to accept a 58% rating for defects?

Table 1.1 Key performance indicators

Key: 10 = totally satisfied, 5/6 = neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 1 = totally dissatisfied.

Source: dti (2002), Construction Statistics Annual, HMSO.

Why then does it appear that construction clients are still unable to find the same levels of value for money as the average car buyer?

The Case for a New Approach to Procurement

The challenge that has been laid at the feet of the construction industry is to transform the diverse and often separate processes of design and procurement of built assets into one single integrated production process.

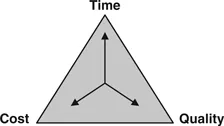

The long established principal drivers for construction procurement have been said to be (it’s no coincidence that the model is pyramid shaped) time, cost and quality as illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Procurement drivers.

Traditionally, the relative importance of these drivers determined the selection of procurement path. The client being asked to identify which of the drivers was the most important – the inference being that it is impossible to have all three simultaneously. Therefore, if time were of the essence then cost and quality would have to be compromised and vice versa. However things have moved on and modern forward thinking construction clients are now taking as read that, just like the car buyer, supply chains can deliver all three of the above, that is: built assets that are delivered on time, within the cost target with zero defects. For example, later in this book the role of frameworks and procurement will be discussed along with the rigorous prequalification processes during which contractors have to demonstrate their ability to deliver added value as a prerequisite to even being placed on a tender list. What now, therefore, do construction clients want from their construction industry partners in the field of procurement? Progressive clients, some of whom have contributed case studies to this book, are now demanding that construction procurement is not detached from their mainstream business operations, organized and delivered by construction professionals operating to their own agendas. Progressive clients are now demanding that procurement mirrors corporate strategies and targets including addressing the following areas:

• Understanding clients’ needs which may, depending on circumstances, include producing solutions that satisfy the following criteria:

– flexible and adaptable facilities,

– maximize use of existing assets,

– immediate start and early finish,

– minimal waste and defects,

– lower and predictable whole life costs,

– greater predictability in cost and time,

– a long-term vision of short-term demands.

• The ability to demonstrate pro-activity and innovation by:

– questioning and challenging clients’ needs,

– develop the ability to question and challenge conventional practice, on the basis that in many cases so far, it has not produced satisfactory solutions.

Collaboration with Clients and Supply Chains

From the mountain of information, reports and statistics that are available, relating to the performance of the UK construction industry during the past 50 years or so, it would appear that the case for a new approach to procuring built assets has been proven. However, despite all of these studies, spanning both the public and private sectors, the UK construction industry is letting its clients down and is perceived by many other industries to be a dinosaur in procurement terms with each new initiative being met with a barrage of scepticism and resistance.

It has been argued that one reason for construction’s comparatively poor performance is that the construction process is unique. This uniqueness is said to be characterized by a wide spectrum of clients as follows:

• Small one-off client or large corporate investor.

• Occasional or experienced client.

• Public or private sector client (Morledge et al., 2002).

Unfortunately, the Luddites within the industry have traditionally seized on these facts to champion the cause of Not In My Industry Thank You! (NIMITY). It could be argued that a similar client/end user spectrum can be found in a number of market sectors, for example computing, but this has not prevented other industries from moving forward and adopting integrated procurement practices. In addition to the above factors the following views have also been identified as peculiarities of construction products and construction (source: adapted from Koskela (2003)):

• The complexity of organization and manufacture of built assets.

• The small extent of the penetration of standardization.

• The high turnover of workers.

• The localized nature of orders of extraordinary diversity.

Why Do So Many Projects Fail to Meet Targets?

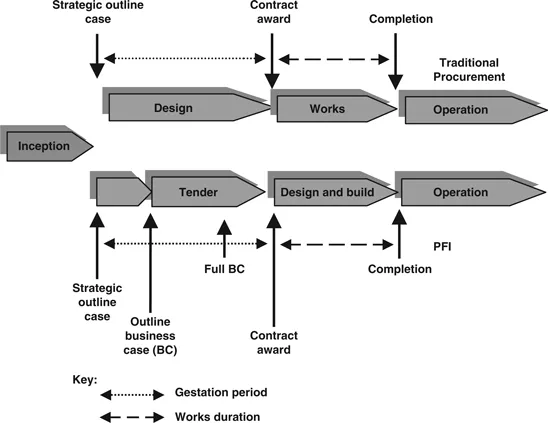

Poor procurement performance transcends both the public and private sectors and some clues for this may come from a government sponsored report. In July 2002 Mott MacDonald prepared a Review of Large Public Procurement in the UK for HM Treasury, as part of the Green Book Review, referred to in more detail in Chapter 3. One of the areas considered by the review was the poor performance of UK public sector construction projects. The study identified what it called ‘high levels of optimism’ as one of the principal causes for poor performance. Optimism being defined as ‘the tendency to underestimate project costs and duration and overestimate project benefits, or the inability to identify and mitigate risk.’ The study continued to identify critical project risk areas that cause cost and time overruns where optimism bias was found. The report calculated an optimism bias, which is expressed as a numerical indication of the level of such bias and can be applied to estimates in order to improve reliability. The report concluded generally that the performance of projects procured using public private partnerships (PPP) was much higher due in part to the much more rigorous approach to the establishment of a robust and realistic business case, combined with rigorous risk analysis. This point is underlined in the case of the new Scottish Parliament project, see Preface, where a similarly complex project, the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, was completed on time and to budget using a PPP/Private finance initiative (PFI) approach. It is not surprising that the optimism bias levels for PPP/PFI projects are lower than for some traditionally procured projects, as more project risks are identified and mitigated at the full business case stage than at the strategic outline case and the outline business case stages. As illustrated in Figure 1.3 the PFI procurement route contains a much more rigorous procedure for business case development than traditional procurement routes. The review concluded that one of the primary objectives of the business case is to identify risk. The Mott MacDonald report also gives an indication of the project risk areas most likely to cause overruns if sufficient risk mitigation strategies are not in place. It would appear therefore that the provision of a sound business case and the correct identification of risk are of great importance in ensuring efficient project delivery. Both of these topics will be discussed in Chapter 2.

Figure 1.3 Review of large public procurement in the UK (source: Mott MacDonald, 2002).

A more controversial explanation as to why large scale public sector projects such as the Channel Tunnel so often are a procurement disaster, is put forward by Bent Flyvbjerg (Mega-projects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition, 2003). Concluding that bad procurement is not just a public sector phenomenon, Flyvbjerg and his co-authors at Aalborg University in Demark, Bruzelius and Rothengatter, examined over 250 mega projects, from all over the world, mainly in the transport sector, undertaken between 1924 and 1998. As well as reaching the same conclusion as Mott MacDonald (2002), namely that civil servants have a tendency to be overly optimistic when it comes to estimating costs and time scales, they go further by suggesting that there is often a good deal of deceit at the planning stages of large prestigious projects by politicians and professionals alike: ‘Cost underestimation and overruns cannot be explained by error and seem to be best explained by strategic misrepre-sentation, namely lying, with a view to getting projects started.’ The authors go on to suggest that criminal penalties should be introduced if this type of conduct were found to be responsible for project excesses!

Is Construction that Unique?

Koskela (1998) rejects the premise that construction is unique and suggests that it is in fact just another production system. According to Koskela the differentiating characteristics often cited by the construction industry of one-of-a-kind nature of projects, site production and temporary teams, are present in several other types of production.

There follows the sequence of events, based on The Machine that Changed the World, Womack et al., of the typical approach towards the procurement of a new motor car around 1970/1980:

• The overall concept is planned in detail by the senior management.

• Detailed drawings and specifications are produced for each part, such as steering wheels, bumpers, etc.

• Only at this point are the organizations, the suppliers (typically 1000–2500), who will actually make the parts, called into the process. However, by this time it is too late to improve the design.

• The suppliers are shown the drawings and asked to produce bids.

• The suppliers know from experience that from the assemblers’ point of view ‘cost comes first’. Therefore, quoting a low price is absolutely essential to winning a bid. This practice leads to implausible bids winning contracts followed by cost adjustments that eventually make the cost per item higher than those of realistic, but losing bidders.

• Since this is the case should they, the suppliers, bid below cost, because as the suppliers also know, once production has commenced they may be able to go back for cost adjustments and variations.

• The mass production assembler has played this game thousands of times and fully expects the successful suppliers to come back for price adjustments.

• The assemblers would dearly like to know the suppliers’ real costs. But these are jealously guarded by the suppliers in the belief that by revealing only the price per component, they are maximizing their ability to hide their true profits ...