eBook - ePub

Business and the Sustainability Challenge

An Integrated Perspective

Peter N. Nemetz

This is a test

Share book

- 536 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Business and the Sustainability Challenge

An Integrated Perspective

Peter N. Nemetz

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

It is vitally important for businesses to have a holistic understanding of the many issues surrounding and shaping sustainability, from competitors to government and political factors, to economics and ecological science. This integrated textbook for MBA and senior-level undergraduates offers a comprehensive overview of the issues of sustainability as they relate to business and influence corporate strategy. It also features a wide range of cases and an extensive discussion of tools to incorporate sustainability issues into strategic decision making, helping instructors and students to build and then apply a solid understanding of sustainability in business.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Business and the Sustainability Challenge an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Business and the Sustainability Challenge by Peter N. Nemetz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Développement durable en entreprise. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Book Outline and Rationale

WHY STUDY SUSTAINABILITY IN A BUSINESS SCHOOL? This is a legitimate question for an undergraduate or master’s-level student who has chosen his/her specific discipline within business and is finishing all course requirements in anticipation of graduation and impending employment. The principal answer to this question and the message of this book is fourfold: (1) there is a significant probability that within the next decade or two at most, the national and international business environment will be radically different from today; (2) this may be, in no small part, because of the enormous ecological challenges facing the globe and the feedback effects they have on our economic systems; (3) by necessity, issues of sustainability will be central to the strategic decision making of mid-sized and major corporations; and (4) any middle-level or senior manager unfamiliar with the issues, both theoretical and empirical, will be placing themselves and their firms at a serious competitive disadvantage.

It can be argued that the goal of achieving sustainable development is probably the greatest challenge that humankind has ever faced. It will require a concerted and coordinated effort among consumers, business, and government. If sustainable development is indeed to be achieved, it can also be argued that the sine qua non is the education of the emerging business elite in the fundamental principles of sustainability, for only with the active engagement of the business community is there any realistic hope that our economic, social, and ecological systems can achieve sustainability.

This presents a major challenge within the confines of a business school as traditional business education has adopted the reductionist approach pioneered by the sciences. This model has withstood the test of time, producing highly educated young graduates who are focused on the theory and empirical data of their chosen discipline. The study of sustainability, within business as in other subject areas, represents a fundamental divergence from this traditional model. This new educational model requires multidisciplinary integration across a wide range of disciplines in the areas of business, economics, social issues, and ecology. Aside from the occasional capstone course at the end of a business degree, there are few, if any, precedents for this holistic approach.

The mission of business schools is to lead in the area of business education, developing new theory, and exploring the significance of a vast array of empirical data. It is also their mission, however, to identify and respond to emerging trends in their environment. One need only read the national press, business magazines, and corporate reports themselves to see the emergence of a dramatic change in the environment of business. Issues of sustainability have been the focus of recent cover pages from such high profile journals as Business Week, The Economist, TIME magazine, and Vanity Fair .

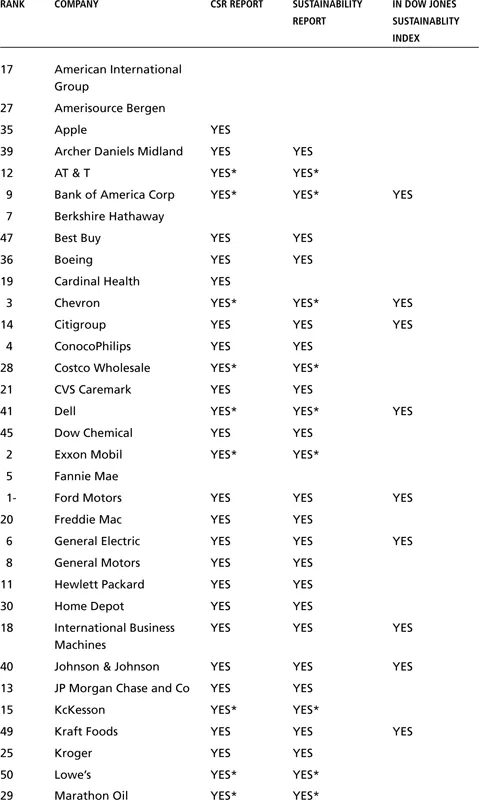

This phenomenon has been mirrored in the proliferation of corporate reports devoted to sustainability and/or corporate social responsibility. Table 1–1, for example, lists the top 50 firms by sales in the Fortune 500. Of these 50, all but 6 have published either stand-alone sustainability or corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports or incorporated significant material on these issues on their websites. Also noteworthy is the fact that 14 of these top 50 appear to be included in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI), although this listing may be incomplete since Dow Jones Ltd. stopped publishing the complete list of companies on their DJS indexes recently.

Table 1.1 Top 50 Fortune 500 companies in 2011

*Company presents both corporate social responsibility and sustainability in the same report Companies with online material only: ConocoPhilips (4), General Motors (8), Hewlett Packard (YESYES), Freddie Mac (20), Valero Energy (24), Marathon Oil (29), Home Depot (30), Pfizer (3YES), Walgreen (32), Boeing (36), State Farm Insurance Cos (37), Archer Daniels Midland (39), United Technologies (44), Best Buy (47), Kraft Foods (49)

Source: corporate websites

While much of the discussion of sustainability issues within the popular press has focused on negative aspects, it is one of the central arguments of this book that many of these sustainability challenges represent extraordinary opportunities for business. This double-sided interpretation is not new to history. The ancient Chinese phrase for “crisis” is composed of two characters: the first represents “danger,” but the second represents “opportunity.” The modern reinterpretation of this historical characterization was enunciated by Michael Porter of Harvard University in a Scientific American essay of April 1991 where he stated that “the conflict between environmental protection and economic competitiveness is a false dichotomy (p. 168).” This thesis has been further developed by Porter in several seminal articles from the Harvard Business Review and the Journal of Economic Perspectives (Porter and Kramer 2006, 2011; Porter and van der Linde 1995a and 1995b). The key message of these articles is simple: there has been a false dichotomy between expenditures on pollution control and corporate profitability. The gist of the authors’ argument is that corporate strategy—the highest level of decision making within a corporation—which recognizes, addresses, and incorporates issues of sustainability can yield significant and “sustainable” competitive advantage.

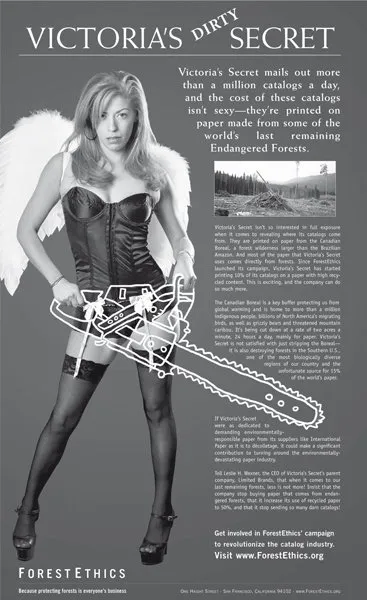

Several major corporations have already adopted the language of sustainability, if not recognized and internalized this transformative principle. For example, Shell Canada’s stated corporate goals are threefold: (1) growth, (2) profitability, and (3) sustainable development. To quote: “over the past decade, issues of sustainability have moved from the periphery of corporate decision making to the centre of corporate strategy” (Symonds 2006). Few industries have been more affected by issues of sustainability than the forest sector. One corporate giant in this sector, Catalyst Paper, lists four reasons why they have moved aggressively to implement sustainability: (1) profit—Catalyst has reduced greenhouse gases by 71% since 1990, saving $16 million per year in fossil fuels; (2) branding—Catalyst has seen the impact of negative press coverage on corporate sales and profitability, which has affected such high-profile companies as Nike and Victoria’s Secret [see, for example, Figure 1–1 and Berman 2011]; (3) market share—a differentiation strategy based on sustainability performance has the proven capacity to attract not only retail consumers, but can also influence B-to-B sales; and (4) stability—there are few things that the corporate sector values more than stability and predictability (Kissack 2007). Leading customers’, competitors’, and government regulatory agencies’ proactivity in the area of sustainability holds the promise of long-term gains.

Figure 1.1 Sample attack ad

The holistic approach to sustainability advanced by this textbook is based on three interrelated components. First and foremost is corporate strategy. But the formation and execution of such strategy cannot be understood without knowledge and appreciation of the economic and political environment in which this strategy must be crafted. Hence, the second major component is government policy—incorporated in legislation and regulations, as well as economic and political theory that help to shape much of this immediate corporate environment. Finally is the scientific framework, largely in the form of ecological theory, which at least in principle provides the intellectual rationale for a significant portion of government policy relating to sustainability issues.

The structure of this textbook is designed to facilitate the understanding of these three principal interlocking components. Several major case studies—one drawn from the manufacturing sector (Interface), one for the renewable resource sector (Ooteel Forest Products), and one from the non-renewable resource sector (Suncor)—are used to introduce many of the relevant concepts. Numerous other shorter cases are used to illustrate other important principles. Appendix 1 provides a short note for instructors and students on possible ways to approach the analysis of the cases presented in this textbook.

What is Sustainable Development?

It is useful to begin a discussion of sustainable development with a thought experiment from a seminal work by William McDonough and Michael Braungart in the Atlantic Monthly of October 1998 entitled “The Next Industrial Revolution.”

If someone were to present the Industrial Revolution as a retroactive design assignment, it might sound like this:

Design a system of production that

- puts billions of pounds of toxic material into the air, water, and soil every year

- measures prosperity by activity, not legacy

- requires thousands of complex regulations to keep people and natural systems from being poisoned too quickly

- produces materials so dangerous that they will require constant vigilance from future generations

- results in gigantic amounts of waste

- puts valuable materials in holes all over the planet, where they can never be retrieved, and

- erodes the diversity of biological species and cultural practices.

Eco-efficiency instead:

- releases fewer pounds of toxic material into the air, water, and soil every year

- measures prosperity by less activity

- meets or exceeds the stipulations of thousands of complex regulations that aim to keep people and natural systems from being poisoned too quickly

- produces fewer dangerous materials that will require constant vigilance from future generations

- results in smaller amounts of waste

- puts fewer valuable materials in holes all over the planet, where they can never be retrieved

- standardizes and homogenizes biological species and cultural practices

This quotation cogently describes the path that the Western industrialized world has followed for the last two centuries. It has clearly yielded enormous economic benefits for many nations and, yet, it is clearly the authors’ intent to argue that such a path is unsustainable. This view is reflected in the challenging piece by the well-known Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson entitled “Is Humanity Suicidal?” (New York Times Magazine, June 20, 1993).

The challenge of sustainability is to find another path for business and government that will continue to generate wealth but with considerably less environmental impact. Two other brief quotations help set the stage for the definition of sustainable development.

- “Only 7% of physical U.S. throughput winds up as product, and only 1.4% is still product after six months” (Friend 1996).

- “Business has ignored its major product lines: pollution and waste. Why would anyone set out to produce something which it cannot sell, for which it has no conceivable use, and for which it might be potentially liable?” (Smith 2007, p. 306).

The phrase “sustainable development” emerged from the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (also known as the Brundtland Report after its chairperson, Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland of Norway). The report was published as “Our Common Future” in 1987 by Oxford University Press. The definition is beguilingly simple: “development that meets the need of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” As originally conceived, sustainable development has three components: (1) the economy, (2) society, and (3) the e...