- 310 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cognitive Science and Mathematics Education

About this book

This volume is a result of mathematicians, cognitive scientists, mathematics educators, and classroom teachers combining their efforts to help address issues of importance to classroom instruction in mathematics. In so doing, the contributors provide a general introduction to fundamental ideas in cognitive science, plus an overview of cognitive theory and its direct implications for mathematics education. A practical, no-nonsense attempt to bring recent research within reach for practicing teachers, this book also raises many issues for cognitive researchers to consider.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Cognitive Science and Mathematics Education: An Overview

Alan H. Schoenfeld

Education and Mathematics

The University of California-Berkeley

Education and Mathematics

The University of California-Berkeley

Twenty-five years ago the phrase "cognitive science" and the field it describes were virtually unknown. Then, at first sporadically and later increasingly through the 1960s and 1970s, an amalgam of researchers from different disciplines, all with common interests in "how the mind works," began to take shape. (For those with an interest in the history of the discipline, Howard Gardner's (1985) The Mind's New Science provides a generally accepted outline of the development of the field.) The cognitive science society was formed in the mid-1970s and its journal, Cognitive Science, first appeared in 1977. The journal's 1984 self-description, which appears on its inside back cover, provides a good definition of the field and the range of topics that are considered central to it:

Cognitive Science is an interdisciplinary journal. It publishes articles . . . on topics such as the representation of knowledge, language processing, image processing, question answering, inference, learning and memory, problem solving, and planning. . . . [It publishes] theoretical analyses of knowledge representation and cognitive processes, experimental studies, . . . descriptions of intelligent [computer] programs that exhibit or model some human ability, protocol or discourse analysis, . . .

Much or all of the foregoing may seem far from the everyday concerns of mathematics educators. (By "mathematics educator" I mean anyone with a primary interest in the teaching and learning of mathematics. Thus mathematics teachers at all levels and researchers in mathematics education are among those designated by the label.) Indeed, some of the things that cognitive scientists do—for example, spending as many as 100 hours analyzing a single 1-hour videotape of a problem-solving session, and perhaps 2 or 3 years writing computer programs that "simulate" the behavior that appeared in that 1 hour of problem solving—must appear odd to someone looking from outside the discipline. A major goal of this chapter is to demonstrate that such apparently odd behavior can be both sensible and useful. More precisely, my goal is to explicate two main ideas; the idea of a "cognitive process analysis" at a very fine level of detail, and of a "constructivist perspective."

Background: Some Alternative Perspectives and Approaches

A basic assumption underlying work in cognitive science is that mental structures and cognitive processes (loosely speaking, "the things that take place in your head") are extremely rich and complex—but that such structures can be understood, and understanding them will yield significant insights into the ways that thinking and learning take place. Analyses in cognitive science tend to be very detailed. They focus on cognitive processes in an attempt to explain what produces "productive thinking." And because the studies are often carried out in tremendous depth, the number of "subjects" in those studies is often quite small.

The cognitive science perspective is best illustrated by some practical examples, in which the "cognitive approach" can be contrasted with the approaches suggested by more conventional methods. To establish a context for our discussion, we begin with a brief description of some of the learning theories, curricular approaches, and research methods that have had significant impact on American educational practice in this century. Having discussed these, we will turn in the next section to some examples of work in cognitive science that have implications for mathematics instruction,

Associationism

E. L. Thorndike's seminal book The Psychology of Arithmetic was published in 1922. Thorndike's learning theory was based on the notion of mental "bonds," or associations between sets of stimuli and the responses to them (e.g. "two plus two" as a stimulus and "four" as a response). According to the theory, bonds become stronger as a result of reinforcement or frequent use, weaker as a result of punishment, or decay as a result of infrequent use. The associationists proposed some general organizational principles for instruction, for example, the principle that bonds that "go together" should be taught together. Translated into pedagogical terms their theoretical approach yielded "drill and practice," a mode of instruction that has had a significant impact on American mathematics instruction. Since the publication of Thorndike's book more than 30 years earlier, drill and practice persisted as a major instructional approach through the 1950s, when I was a student (and used "flash cards" to practice my arithmetic facts). It still exerts a strong influence on the design of many contemporary CAI (computer-assisted instruction) programs. The associationists made some fairly straightforward assumptions about knowledge organization (i.e. about "what's in a person's head" and how it's organized) and had a correspondingly straighforward learning theory. They had little interest in detailed explorations of cognitive structures.

Gestaltism

A different stance was taken by the gestaltists, who believed that mental structures were much more complex than the associationists believed, and that the complexity of such structures needed to be taken into account in teaching and learning. A classic piece of gestaltist exposition is Max Wertheimer's (1959) Productive Thinking, originally published in 1945. In it Wertheimer decried rote learning and pointed to the limitations of a drill-and-practice approach. Although such instruction, he conceded, did result in students' "mastering" certain procedures, knowledge acquired in rote fashion was likely to be superficial and thus not likely to be either flexible or useful in a range of situations.

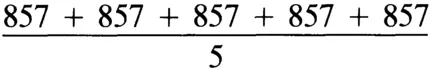

Wertheimer argued his case with a number of pointed examples. A particularly telling one was that many students who were considered to have mastered arithmetic were indeed able to carry out the arithmetic procedures they had studied but had little or no understanding of the meaning of those procedures. Students whom he interviewed would often work problems like

by laboriously adding the five identical terms in the numerator, and then dividing the result by five—all of which is completely superfluous if you understand what the problem calls for. (Wertheimer also quoted a friend's son as saying that he understood arithmetic perfectly well. The child could add, subtract, divide, and multiply with the best of them. The only problem was that the child never knew which method to use.)

The most famous of Wertheimer's examples deals with the "parallelogram problem," the problem of finding the area of a given parallelogram that has base B and height H (Fig. 1.1a). Wertheimer observed a class that had been taught the standard procedure for finding the area, where moving a triangle from one part of the parallelogram to another part creates a rectangle whose area is easy to find (Fig. 1.1b). The students did well and their teacher was proud of their performance. But when Wertheimer asked the students to find the area of parallelograms in nonstandard positions (e.g. Fig. 1.1c) or to find the areas of novel figures to which the same argument applied (e.g. Fig. 1.1d), the students were unable to do so. They (and the teacher) complained that Wertheimer's questions were not fair; the class hadn't studied those kinds of problems.

From the gestaltists' point of view, the questions were fair. The answers to both questions should be apparent if one understands the underlying principles and structures from which the specific arguments the students had memorized could be derived. The gestaltists believed in very rich mental structures and felt that the object of instruction should be to help students develop them. The main difficulty was that the gestaltists had little or no theory of instruction. Although their goal was similar to that of many researchers today (myself included), their theories did not suggest specific instructional methods that could be used to attain it.

FIG. 1.1. The "parallelogram problem."

Behaviorism

"Radical behaviorists" such as B. F. Skinner (see, e.g., Skinner, 1958) took a stance that was compatible with that of the associationists, but more extreme. In direct opposition to the gestaltists, Skinner held that any emphasis on "mentalism" or attention to "mental structures" was misplaced. He argued that learning performance could be defined solely in terms of observable behaviors ("behavioral objectives") and that learning was best thought of as the result of an individual's interactions with the environment. Thus, behaviorist learning theory focuses on arranging the environment so that optimal interactions take place. Resnick (1983) described the behaviorist approach as follows:

[Skinner] and his associates showed that "errorless learning" was possible through shaping of behavior by small successive approximations. This led naturally to an interest in a technology of teaching by organizing practice into carefully arranged sequences through which the individual gradually acquires the elements of a new and complex performance without making wrong responses en route. This was translated for school use into "programmed instruction"—a form of instruction characterized by very small steps, heavy prompting, and careful sequencing so that children could be led step by step toward [the] ability to perform the specified behavioral objectives, (pp. 7-8)

Whether in programmed instruction or in other applications, the emphasis on small steps and careful sequencing is central to the behaviorist approach to instruction. This approach, pioneered by Robert Gagné (see, e.g. Gagné & Briggs, 1979), was based on the hypothesis that the right sequence of experiences, repeated with adequate frequency, should generate the right learning. Thus, the bulk of one's attention should be on analysis of subject matter. Gagné focused on constructing careful task analyses, which entails decomposing the material to be learned into small building blocks that are mastered individually and later combined into larger units of competency. (I should note that part of the theory included "positive reinforcement" for getting the right answer. Rats and pigeons in Skinner's experimental laboratories were awarded small bits of food when they did well. In an application of the same theory to human learning, my fellow students and I were awarded gold stars when we did well.)

Curricular Trends

For the first half of this century, mathematics curricula in schools were relatively stable. Then, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, our curricula began a series of dramatic swings, each lasting about a decade. The first major shift in curriculum came about in the 1960s in response to a perceived national crisis. The Soviet Union had been the first in space in 1957, with the artificial satellite Sputnik, and the first to achieve manned orbital flight, in 1961. In response to these achievements and to a perceived lack of quality in school curricula, American scientists and mathematicians concentrated intensely on updating and upgrading American science and mathematics instruction. The "new math" and the "alphabet curricula" (BSCS, PSSC, etc.) in the sciences—all with significant mathematical and scientific content—were developed.

A decade later, the new mathematics curricula were generally considered to be failures. The public perception was that school children not only failed to understand the new math, but were no longer able to add, subtract, multiply, or divide. This nationwide reaction engendered the "back to basics" movement. For the next 10 years, teachers once again relied on drill and practice to insure that their students would have basic "foundation" skills in mathematics.

It wasn't long before serious cracks developed in that toundation. It became clear that students were memorizing rote procedures without understanding them, that they were not any better at them than the previous generation of students had been, and that they could not use them in problems that called for even the simplest application. (Evidence documenting these statements may be found in the periodic National Assessments of Educational Progress; see, e.g., Carpenter, Lindquist, Matthews, & Silver, 1983. It may also be found in trends in nationwide SAT mathematics scores, which, despite the emphasis on basic skills in the 1970s, marched steadily downward from 1964 through the early 1980s.) In a major swing of the curricular pendulum, "problem solving" was (re)born in the late 1970s in reaction to the failures of the back to basics movement. In its influential 1977 position paper, the national Council of Supervisors of Mathematics asserted that "learning to solve problems is the principal reason for studying mathematics." Three years later...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- 1 Cognitive Science and Mathematics Education: An Overview

- 2 Foundations of Cognitive Theory and Research for Mathematics Problem-Solving

- 3 Instructional Representations Based on Research about Understanding

- 4 Cognitive Technologies for Mathematics Education

- 5 Problem Formulating: Where Do Good Problems Come From?

- 6 From the Teacher's Side of the Desk

- 7 New Knowledge about Errors and New Views about Learners: What They Mean to Educators and More Educators Would Like to Know

- 8 What's All the Fuss about Metacognition?

- 9 Cognitive Science and Algebra Learning

- 10 Cognitive Science and Mathematics Education: A Mathematician's Perspective

- 11 Cognitive Science and Mathematics Education: A Mathematics Educator's Perspective

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cognitive Science and Mathematics Education by Alan H. Schoenfeld in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Bildung & Bildung Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.