eBook - ePub

Lighting Technology

Brian Fitt, Joe Thornley

This is a test

Share book

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lighting Technology

Brian Fitt, Joe Thornley

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Anyone working with lighting in the entertainment industries will find this an immensely readable source of information. The authors, themselves experienced lighting practitioners, have collected a wealth of essential lighting technology and data into one comprehensive reference volume in an accessible, jargon-free style.

The new edition of this popular text covers the very latest technology, including advances in lamps, motorised lights, dimmers and control systems and current safety regulations.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Lighting Technology an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Lighting Technology by Brian Fitt, Joe Thornley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Theater. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Every year we all hope there will be a wonderful new light source but tungsten and discharge still dominate the lighting industry. To aid the production of a higher light output from luminaires, lamp manufacturers have made some progress by producing tungsten lamps with more compact filaments and discharge lamps with shorter arcs. This allows the concentration of the light output by utilising the optics more efficiently. There are hints of important progress in the production of light from Light Emitting Diodes with suggested outputs of around 100 lumens/W. One tremendous advantage of LEDs is that the majority of their output is in the visible spectrum, thus avoiding the generation of ultraviolet (UV) and infrared. At this stage, it is difficult to envisage devices such as these being used in conventional luminaires.

Since the previous edition, the most significant advances have been in the motorised light sector. To overcome the restricted range of projected patterns and colours, the manufacturers of moving lights are looking to computer generated images coupled with digital projection. This enables real time programming of the luminaire output with an almost unlimited pattern and colour range. The main problem is obtaining a high enough light output to blend with existing lighting arrangements. At present, most digital projection is aimed at audio-visual presentations and cinema projection, where the screen brightness is of a fairly low order.

Fluorescent lighting, which was introduced on a fairly large scale as an aid to producing more efficient lighting, has now settled down as a soft source. It is now generally used with small tungsten and discharge sources in hybrid studios, such as news and talking head areas, to create comfortable working conditions.

New dimmers have been introduced which have moved away from thyristor technology to provide a sine wave output (almost)! This enables a controlled switching of the output waveform, thus avoiding the use of chokes to smooth the output, which has the advantage of reducing some of the problems with mains borne interference and lamp sing but most significantly, lowers the weight of the dimmer. Manufacturers are now integrating dimmers into the suspension system, with control by DMX loops.

Control systems have become increasingly sophisticated due to the need to control large numbers of moving lights. DMX512 appears to have been adopted as the standard form of control signal.

As a result of more stringent budgets, particularly in television (TV), equipment is not being replaced as frequently as it used to be. Most of the impetus for change is either caused by a safety problem or the need to introduce the latest ‘gizmo’.

We hope you will find the new streamlined edition as informative as the old one.

2

Lighting the subject

From the time when the Savoy Theatre, London, was first lit by electricity in 1881, the instruments used for artificial lighting have developed from very crude flood sources to the sophisticated moving light sources of today.

Early light sources were generally floodlights with little or no finesse. As taste became more refined, so did the lighting. The majority of lighting is placed at a reasonable height above the acting area. The reasons for this are quite simply that we do not wish the acting area to be full of equipment. This holds true for most lighting equipment, but in a TV or film studio the floor is also cluttered with cameras and booms, etc. As members of the human race we are conditioned that light is above us and at an average of about 45° to any standing object on earth. This fact lays down the most important ground rule for the artificial lighting of any scene. Artists throughout the ages have appreciated the light sources available to them. The sun provides a wonderful key light with warm rich colours and the blue sky provides a softlight of cool brilliance.

The subject may be either a performer or a static object and the lights have to be positioned and controlled to give the desired effect. Sometimes, compromise is necessary due to the position of scenery, cloths, and other objects which may give rise to unwanted shadows. The choice of luminaires for the lighting designer is extremely wide and varied, but all will have their particular favourites because they know that they can produce acceptable and repeatable results from some of the devices used in the past. Lighting designers these days can use lights from another branch of the industry to give some effects that were previously unobtainable.

To the untrained eye, lighting, either in the theatre, TV studio, on a film set or in a huge ‘Pop rig’ looks somewhat similar. However, closer inspection reveals that the luminaires used in the theatre are somewhat different to those used for film and TV and these days will probably have more in common with the ‘Pop’ industry. We find that stage lighting designers now use Parcans together with automated luminaires using tungsten and discharge sources. Many of the luminaires used on stage and for that matter in the pop world are now being used more and more in TV.

In our everyday lives as human beings, we go around in illumination that can vary from the minimum amount on a moonlight night to a maximum of an overhead sun in the Sahara desert. Other than a psychological difference, we are not disturbed by the differences between gloomy, grey overcast days and the intense blue skies of winter when the atmosphere is at its clearest. Visually, we are not worried by a lack of shadow detail, and on other occasions we see no problems with the intense black shadows created by sunlight. We do become disturbed however, by green light applied to the human skin, we also become rather unnerved by lighting when it comes from below subjects and not from above. In our everyday lives we are conditioned by the most basic form of lighting which consists of a reasonably well balanced mixture of sunlight and light from the blue sky.

In the absence of light from the sky, such as on the moon, we see extremely contrasting pictures due to one light source only, namely the sun. We feel much better when we are bathed in warm sunlight and not standing in the cool of a grey day. Some of this is caused by the generation of vitamins by sunlight, but mostly it is psychological. It is interesting to note that we also feel better on a sunny day in the middle of a cold winter. Red and yellow give us a cosy feeling, and this is probably occasioned by our mental stimulation with the association of the sun. It's a strange fact that as colour temperature increases towards the blue end of the spectrum, we do not necessarily feel warmer and we actually associate blue with cool conditions. Green has a refreshing quality, which is probably occasioned by the response of the eye which is at its peak with the green portion of the spectrum. We view black as a very sombre colour and associate it with the macabre. We generally associate white with coolness and a feeling of something that is quite unspoilt; it's interesting to note how disturbed we are by snow when it has become muddied, as the thaw sets in. From this short list of examples, it must become obvious that we can associate colours with a sense of stimulation of appreciation within the viewed scene, and many of the effects used in artificial lighting are based upon these feelings.

Light in its most basic form, daylight, consists of a mixture of sunlight and skylight. These can be analysed as the sun which provides extremely hard light that gives well defined shadows and a sense of depth; and the sky which gives very soft diffused lighting without any obvious shadows. The reasons that the light behaves in different ways is that the sun is a very small source in comparison to the subjects it illuminates, hence it produces the hard shadows, whereas the sky is an extremely large source in area and thus produces almost shadowless lighting. Note the term almost because no lighting is shadowless and if an object blocks some of the light rays it will produce a shadow, however diffuse!

‘Soft’ or ‘hard’ is a relative term. For instance, a softlight can give reasonably hard shadows, whereas a larger softlight positioned at the same distance, will produce a softer shadow. Conversely, a Fresnel lens luminaire with a brushed silk diffuser fitted can give quite a soft result when used close to the subject.

It must be remembered that both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ light have the same physical properties. ‘Hard’ light consists of light rays going in straight lines from a very small source to the subject, whereas ‘soft’ light consists of the same light rays emerging from a larger source area going to the subject in straight lines from a variety of angles (see Chapter 6, Figure 6.18).

An important factor in the use of softlights, which is often forgotten, is that they have two planes of illumination, the horizontal and vertical. As the width of the softlight becomes greater, so the vertical shadows become more diffuse. When the height of the softlight is increased the horizontal shadows become more diffuse. Obviously, there is a finite size to softlights, but the most effective for many subjects are those that are reasonably wide in relation to their height.

We hear the term the ‘quality of light’ – all light is essentially the same, except for the colour. However, when we look at light from a carbon arc it appears to have a very hard, sharp, focused quality, whereas subjects lit by fluorescent lighting have a much softer look. The difference, on the surface, between a 150 A carbon arc with a Fresnel lens, and a4kW HMI with a Fresnel lens, is very slight. In practice the HMI appears to be a softer quality. These observations generally apply to hard light, whereas when we examine soft light, irrespective of the source, the results are always somewhat similar.

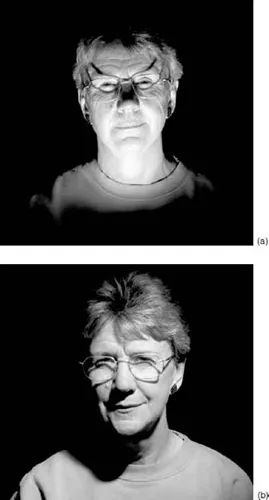

What constitutes good or bad lighting is very much the opinion of the observer, but there are certain ground rules which can define the quality of lighting as perceived by the viewer of the scene. A good example of bad lighting, when shooting film and TV material, is the incorrect colour of the light sources or choosing the wrong colour correction. The balance between modelling lights and fill lights has to be closely controlled or it may give problems with contrast and exposure and as well as creating ‘grainy’ or ‘noisy’ pictures. Highly saturated colours when used for TV give a very overpowering result due to the size of the screen image. Extremely steep lighting from above a person will give very distorted features on the face and for that matter if the lighting is from beneath (see Figure 2.1a and b). It is essential for film and TV to have a good contrast range within the scene to avoid a flat result. This is not to say that lighting has to obey a fixed set of rather boring rules but the choice of light sources, colour and special effects has to be carefully thought out and balanced against what is stimulating and what is annoying. The very best lighting for film and TV will be largely unnoticed by the viewer and, if this is the case, the lighting designers’ aims will have been achieved.

Figure 2.1 (a) Underlit; (b) Steep lighting

Most of the lighting conventions used in the film and TV industry emerged from the earlier days of film when all the material was shot in black and white. It was obviously extremely important to give a sense of depth to pictures and when one sees some of the original extremely old movies that were made without the use of enhanced artificial light, and shot purely by daylight, the results are somewhat flat and uninteresting. During the late 1920s and early 1930s increasing use was made of high powered light sources in the film industry and these enabled the lighting cameramen to achieve better results than previously. Hollywood discovered that a key light placed at the correct angle could enhance the artist greatly. Thus we had ‘Paramount’ lighting where a hard key light was fairly low and straight onto the face, which enhanced the beauty of ladies with high cheekbones, Marlene Deitrich being one supreme example. The film makers also learnt from portrait painters and noted that a more interesting result could be given when the key light was not straight to the face, but taken to the side and thus had a type of lighting known as ‘Rembrandt’ portraiture. Probably the pinnacle of black and white film lighting is that of Citizen Kane, with its highly dramatic portraiture and extremely imaginative use of shadows and highlights. The advent of colour film, with its lower contrast range meant that the lighting cameramen had to control the lights to a narrower band of illumination, using colour more imaginatively to obtain contrast.

Whereas the theatre and the concert arena have to be lit for the entire viewed scene, the film and TV industry is lit ‘piecemeal’. Television studios will often record material using several cameras which will require the scene being lit as a whole. Traditionally, the film industry has shot scenes using one camera position at any one time, therefore the lighting is only adjusted for that camera position. When the camera position is moved, the lighting is re-adjusted to suit the new position. This has two distinct advantages, one of which – you only need one camera and secondly – not too many lights. This technique is also used in TV these days, particularly on location. A problem that exists with this technique is that continuity has to be watched very carefully, thus sun...