![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

The major emerging and transition economies of the world – Brazil, China, India, and Russia – are adopting or considering the adoption of IFRS, not US GAAP, in an effort to become integrated in the world’s capital markets and attract the investment necessary to finance their development … There is clear momentum towards accepting IFRS as a common financial reporting language throughout the world … Investors are able to make comparisons of companies operating in different jurisdictions more easily.

(Tweedie, 2007, p. 2) 1

[T]he most likely effect of local politics and local market realities on IFRS will be much less visible … I believe the primary effect of local political and market factors will lie under the surface, at the level of implementation, which is bound to be substantially inconsistent across nation.

(Ball, 2006, p. 16)

These two comments represent contrasting attitudes towards IFRS adoption and implementation. Although there are ample benefits in adopting IFRS as a common financial reporting language (Tweedie, 2007), an underlying question remains over the implementation issues because of political and market factors (Ball, 2006).

Debates persist around the justification for IFRS adoption. Two schools of thought exist, and the first is very supportive of the adoption of IFRS, arguing that the adoption of IFRS increases the transparency of financial information and the globalisation of capital markets, and attracts foreign direct investment (FDI) (Taylor and Turley, 1986; Wolk et al., 1989; Larson, 1993; Chamisa, 2000; Tyrrall et al., 2007). The second school of thought, however, is negative about the adoption of IFRS and argues that the Anglo-American nature of IFRS will not be beneficial for the developing countries because of various related factors, e.g. economic, social and, cultural differences (Nair, 1982; Hove, 1989; Perera, 1989; Wallace, 1988, 1993; McGee, 1999; Saudagaran and Diga, 2000; Abd-Elsalam and Weetman, 2003). Some researchers provide mixed opinions on IFRS adoption (Choi and Mueller, 1984; Chandler, 1992; Belkaoui, 2004; Ashraf and Ghani, 2005). Furthermore, financial scandals in the USA and Asia have focused attention on the regulatory bodies (Mitton, 2002; Baek et al., 2002; Tweedie, 2007; Trott, 2009; Bushman and Landsman, 2010). As the IASB possesses no powers of its own to enforce the adoption of its standards, it has to rely on persuading national jurisdictions or national regulators (Banerjee, 2002; Ball, 2006; Ahmed, 2010; Siddiqui, 2010). The relevant EU regulation 2 (1606/2002 of 19 July 2002) requires that all listed EU companies from 1 January 2005 onwards must prepare their consolidated accounts to conform to mandatory IFRS, representing considerable progress towards the goal of global adoption of the IASB’s common financial reporting language (i.e. IFRS) (Hodgdon et al., 2009). This announcement has prompted developing countries to think about their position with regard to IFRS compliance (Tyrrall et al., 2007).

There is an increasing amount of literature on compliance with IFRS, in particular with regard to developed countries (Dumontier and Raffournier, 1998 [Switzerland]; Murphy, 1999 [Switzerland]; Street et al., 1999, 2000 [developed and developing countries]; Street and Bryant, 2000 [companies with and without the US listings]; Glaum and Street, 2003; Haller et al., 2009 [Germany]; Yeoh, 2005 [New Zealand]; Dunne et al., 2008 [UK, Italy and Ireland]; Tsalavoutas, 2009, 2011 [Greece]; Cascino and Gassen, 2010 [Germany and Italy]; Lama et al., 2011 [Spain and the UK]). Most previous studies have been concerned with settings where the use of IFRS is voluntary or not subject to national enforcement (Street et al., 1999; Tower, 1993). Following the widespread adoption of IFRS, attention has turned to the extent to which companies comply with IFRS in a mandatory setting (Schipper, 2005; Brown and Tarca, 2005).

However, little attention has been paid to developing countries. Only 11 studies have been conducted on mandatory IFRS compliance in developing countries (see Table 1.1). Table 1.1 shows that companies in these countries do not comply fully with IFRS disclosure requirements and that low compliance levels are common. There are various reasons for IFRS non-compliance: firstly, in terms of language familiarity, the levels of compliance with familiar aspects of IFRS disclosure requirements are significantly higher than the levels of compliance with relatively unfamiliar aspects of IFRS disclosure (Abd-Elsalam and Weetman, 2003 in Egypt). Secondly, from the view of regulatory aspects, significant changes are exhibited in the regulated environment (Al-Shiab, 2003 in Jordan; Abdelsalam and Weetman, 2007 in Egypt; Al-Shammari et al., 2008 in the Gulf Cooperation Council [GCC] member states) – for instance, corporate governance regulations are a very effective mechanism for the implementation of IFRS (Al-Akra et al., 2010 in Jordan). Thirdly, IFRS compliance may be difficult due to poor levels of enforcement – an example of this is that no action has been taken against managers, directors, or auditors for violating accounting rules and regulations in Jordan (Al-Shammari et al., 2008); Finally, in terms of cost-benefit analyses, big companies are inclined to comply with IFRS, whilst small companies tend to decide that the costs exceed the benefits (Fekete et al., 2008, in Hungary). Omar and Simon (2011, p. 184) suggest that ‘Regulators should take into consideration the costs and the benefits associated with any plans to increase disclosure for firms which are small, not profitable, not listed in the first tier, in the services sector and not audited by the Big Four.’

It is also found in prior research that Bangladesh has the lowest level of disclosure in terms of IFRS mandatory disclosures (see Table 1.1). These mandatory studies did not reveal the reasons for non-compliance and have not yet reached any comprehensive conclusions, either in a comparative study or in a single country study. The findings provide solid grounds for concerns regarding the implementation of IFRS in a developing country such as Bangladesh where the level of disclosure is so low. It is therefore important to study the factors which are affecting the implementation of IFRS in Bangladesh, as an example of a developing country.

The next section describes the motivation of the study followed by the research questions. Then, I outline the research methods to be used in the study. The summary of findings and the structure of the book are presented next.

Table 1.1 Summary of the findings of mandatory studies on IFRS compliance in developing countries

| Author(s) | Country | No. of Comp. | Average Disclosure | Sources |

|

| Ahmed and Nicholls(1994) | Bangladesh | 63 | 51.33% | Appendix 3, p. 75 |

| Abd-Elsalam and Weetman (2003) | Egypt | 89 | 83% | Tables 8–9, pp. 78–9 |

| Al-Shiab (2003)a | Jordan | 50 (300 firm-years) | 1998: 51 %; 1999: 54%; 2000: 56% | Table 6.23, p. 338 |

| Ali et al. (2004) | Bangladesh India Pakistan | Bangladesh 1 18; India 219; Pakistan 229 | Bangladesh [78%]; India [79%]; Pakistan [81%] Range: 78%–81% | Tables 5–6, pp. 194–5 |

| Akhtaruddin (2005) | Bangladesh | 94 | 43.53% [Range: 17%–71.5%] | Table 10, p. 413 |

| Abdelsalam and Weetman (2007) | Egypt | 1991–92:20 1995–96:72 | 1991–92:76% 1995–96: 84% | Tables 4–5, pp. 93–4 |

| Hasan et al. (2008) | Bangladesh | 86 | Not mentioned | Table 1, p.200 |

| Al-Shammari et al. (2008) | GCC member countries | 436 | Bahrain [65%]; Kuwait [72%]; Oman [65%]; Saudi Arabia [75%]; Qatar [69%]; UAE [75%] Range: 56–80% | Table 8, p. 17 |

| Fekete et al. (2008) | Hungary | 18 | 62% | Table 4, p. 8 |

| Al-Akra et al. (2010) | Jordan | 80 | 1996: 54.7% 2004: 79% | Table 5, p. 182 |

| Omar and Simon (2011)b | Jordan | 121 | 83.12% Range: 63.87–93.75% | Tables 12–16, pp. 180–3 |

Motivations and rationale of the study

Bangladesh has received considerable attention from international investors following its adoption of an ‘open door’ economic policy aiming to encourage investment. The country’s economy has been described as one of the fastest growing markets in emerging nations (World Bank, 2010). Over the past decade (2000–10), two reports on the observance of standards and codes (ROSC) have been published by the World Bank regarding accounting and auditing practices in Bangladesh. In the first report, the World Bank (2003, p. 1) states that: ‘Accounting and auditing practices in Bangladesh suffer from institutional weaknesses in regulation, compliance, and enforcement of standards and rules.’ The report also notes that Bangladesh lacks quality corporate financial reporting. After six years had passed, in the follow-up report, the World Bank (2009, p. 25) provided the same sentiments regarding low compliance with accounting standards. The World Bank (2009, p. 10) observed that;

Efforts to implement IFRS for listed companies and other public interest entities should be accelerated. This will require either more frequent updating of BAS or simply adopting IFRS explicitly … Full implementation will also require that current donor assistance to ICAB be maintained, to allow for much needed professional development and expansion in the number of trained auditors and accountants.

The World Bank Newsletter (2009, p. 1) noted that ‘With a population of 150 million, Bangladesh has only 750 Chartered Accountants; far too few to meet the needs of the growing economy.’

Bangladesh is one of the world’s poorest countries, ranking third after India and China in the extent of its poverty levels (International Fund for Agricultural Development – IFAD, 2006). With an estimated population of over 150 million and per capita income of US$444, Bangladesh has the highest population density in the world (948 per sq km.). More than 63 million people live below the poverty line (United Nations Population Fund – UNFPA, 2008). Bangladesh faces the challenge of achieving accelerated economic growth and alleviating the massive poverty that afflicts nearly two-fifths of its people (UNFPA, 2008). Accordingly, the motivations of this book, on implementing IFRS in developing countries with special reference to Bangladesh, are given below.

Globalisation and the mobilisation of capital markets

Bangladesh as a country possesses distinct features which are relevant in consideration of harmonisation and global convergence issues, including the effects of globalisation and the mobilisation of capital markets. The concept of globalisation may be considered to represent the emergence of an international community where interests and needs can be shared from the developed world (Grieco and Holmes, 1999). Despite the challenges and obstacles of achieving targeted economic growth, Bangladesh made liberal market reforms in the mid-1980s, during the military-backed government (Ahmed, 2010). The aim was to move towards an open economic regime and integrate with the global economy. During the 1990s, notable progress was made in economic performance and, therefore, foreign aid dependency was significantly decreased. For instance, the annual economic growth rate (GDP %) increased during the democratic era: in the 1990s, it was 5.2%, compared to 1.6% during the military era in the mid-1980s (World Bank, 2011; see also Chapter 4).

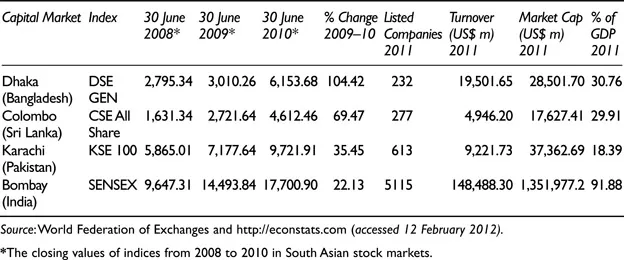

Table 1.2 Comparison of stock market performances in South Asia

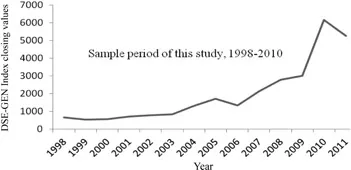

The stock market in Bangladesh has existed for more than 55 years and has experienced rapid growth – e.g. the price indices have increased 104.42% compared to other stock markets in South Asia (see Table 1.2). 3 Significant growth in the numbers of listed companies and their volume of trading has been evident from 1998 to 2010 (see Figure 1.1). As of 30 June 2011, the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) had 232 listed companies, with a market capitalisation of US$28,501.70 million, whereas the market capitalisation of 31 December 1998 was just US$1,034.00 million with around 150 listed companies. 4 While global stock markets have taken a beating, the DSE has performed reasonably well; it was the sixth best performing exchange in the world on a currency-adjusted basis and Asia’s best performing benchmark after China’s CSI 300 Index in 2008 (Bloomberg, 2008; Financial Express, 2008). Despite the fact that market capitalisation has been increasing significantly since 1998, the size of the country’s capital markets remains low (World Bank, 2011).

Figure 1.1 Performance of DSE-GEN Index, 1998–2011

The opportunity for FDI

Unlike in many other developing countries, FDI is not a major source of investment in Bangladesh. Indeed, FDI fell by 16% from 2006 to 2007 (UNCTAD, 2008). Net FDI turned negative in 2009 (US$110 million) (World Bank, 2011). This is possibly because of the adverse impact of various economic and political factors, including weak macroeconomic conditions, the predominance of public sector enterprises, a small domestic market, and political instability (Financial Express, 2011). Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB, 2005) noted that corruption is the main obstacle to attracting FDI into Bangladesh. Moreover, foreign investment has not increased since the 1970s (Financial Express, 2011). Foreign investors hold only 1% of shares on the DSE market (World Bank, 2011). In this regard, if companies in Bangladesh were to implement IFRS effectively, then this practice might attract foreign investors who rely on financial information provided according to international st...