![]()

Chapter 1

Defining a Problem: Modern Architecture and the Baroque

Maarten Delbeke, Andrew Leach and John Macarthur

The Persistence of the Baroque in Modern Architecture

The idea that the writing and teaching of art and architectural historians has lent values and ambitions to the development of twentieth-century architecture is now widely accepted by its scholars. The studies that have considered this coincidence, and especially those written since the turn of the twenty-first century, have demonstrated the clear intellectual debt of modern architecture to modernist historians who were ostensibly preoccupied with the art and architecture of earlier epochs.1 This volume extends this work by contributing to the dual projects of writing both the intellectual history of modern architecture and the modern history of architectural historiography. It considers the many and varied ways that historians of art and architecture have historicized modern architecture through its interaction, in particular, with the baroque: a term of contested historical and conceptual significance that has often seemed to shadow a greater contest over the historicity of modernism.

As the following chapters attest, whether this traffic of ideas was driven by the historian or fostered by the architect, the century leading up to the various postmodern declarations for the new historicism that emerged around 1980 evidences a long process of sifting through historical research and distilling from it moments – be they forms, concepts or models of the architect’s practice and its scope – against which to calibrate the ambitions of architecture across the modern era. By considering the many examples presented here and the sometimes surprising extent of their inter-referentiality and their shared dependence on certain sources – even when put to drastically different uses – this book interrogates an historiographical phenomenon that is widely appreciated but rarely called to account.

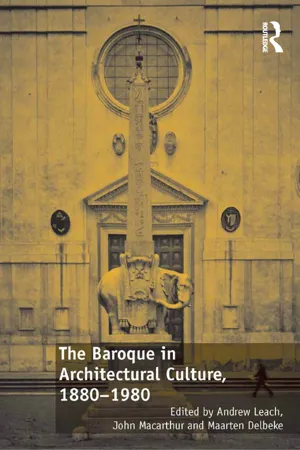

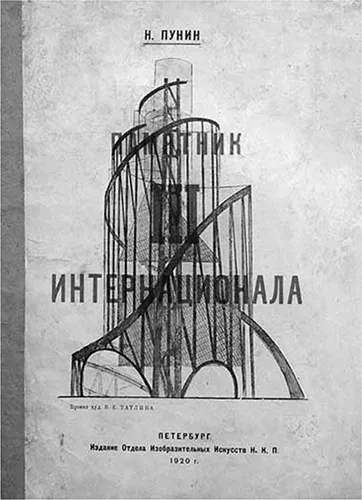

In his landmark teleological history of modern architecture (Space, Time and Architecture, 1941), Sigfried Giedion gave this theme its most potent expression in his pairing together of images of two iconic spirals: on one hand, Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1919–20, Figure 1.1); and on the other, Francesco Borromini’s dome for Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza (1642–60, Figure 1.2). The values shared between the baroque age and the modern were thus encapsulated on a single-page spread. As Giedion put it, writing of Sant’Ivo, Borromini accomplished “the movement of the whole pattern made up by its design flows without interruption from the ground to the lantern, without entirely ending even there.” And yet he merely “groped” towards that which could “be completed effected” in modern architecture – achieving “the transition between inner and outer space.”2 We appreciate the instrumentality of Giedion’s history better than his readers did in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, just as we now better understand how his analyses of these two projects absorbed and advanced the scholarship and criticism of such intellectual forebears as Jacob Burckhardt, Heinrich Wölfflin and, especially, August Schmarsow. This pairing of architectural works nonetheless emerges from the history of modern architecture as a moment of clarity in which history was rendered as a repertoire of ideas and examples that could be placed into conversation with the present and its recent past. This moment expressed a multivalent relationship that had been explored for several decades up to the time in which Giedion wrote and which would continue to fuel history’s stake (and therefore that of the baroque) in modern architecture in the post-war years.

The century-long modernist trajectory this book follows tracks the parallel path taken by historiography itself. Indeed, if Wölfflin’s Renaissance und Barock (1888; Renaissance and Baroque, 1964) is one kind of founding document for the modern historiography of architecture, then the baroque quickly figures in that field’s core problems.3 These, namely, are the questions of how architecture changes its appearance, function and meaning over time; and of how to present realized works of architecture as moments within processes of change. Wölfflin enacted a conceptually crucial divorce between architecture and its historical causes, demonstrating that one could refuse to regard the building as a symptom of the pathologies that give rise to it and treat historical problems that were not merely circumstantial in nature. In 1888 and in Wölfflin’s hands one could, consequently, consider the visual experience of the façade of Il Gesù without giving thought to the Jesuit Order. That this would have been impossible a century later speaks to the historical contingencies of Wölfflin’s positions, which nonetheless – and as the following chapters demonstrate again and again – informed the way baroque architecture was conceived and apprehended in the intervening decades.4

Figure 1.1 Monument to the Third International, by Vladimir Tatlin

Source: Cover of Nikolai Punin, Pamiatnik III Internatsionala (St Petersburg: NKP, 1920).

Figure 1.2 Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, by Francesco Borromini, Rome, 1642–60

Source: Photograph by Andrew Leach.

If Renaissance und Barock and Space, Time and Architecture describe two fundamental moments in the figuring of the baroque into the intersecting paths of modern architecture and modern architectural historiography, they have also become obvious starting points for considering the modern traffic of ideas between the historian and the architect. While the baroque continued to figure in the way that critics, theoreticians and historians thought through the parameters and problems of modern architecture, the debt these owe to thinking done by historians around the baroque in particular is not always (if at all) obvious to present-day discourse. (Vidler, in particular, has done much to clarify the means by which historical scholarship of such figures as Emil Kaufmann and Rudolf Wittkower belied its contemporaneity.5) As several of the following chapters demonstrate, through Sigfried Giedion (Costanzo, Pelkonen), Steen-Eiler Rasmussen (Raynsford), Bruno Zevi (Dulio), Christian Norberg-Schulz (Lauvland) and other key figures in this relationship, the problems of the baroque were seen to persist in the domains of modern architecture and the city: space versus monumentality, regional versus universal style, universalism versus cultural specificity, tradition versus renewal.6

Of greater import in the conceptualization of modern architecture, though, are those abstractions drawn from scholarship on the baroque that leave aside the baroque itself – those abstractions that proved mutually constructive in the concurrent development of modern architecture and modern historiography. From the 1870s and 1880s onwards, space, experience, visuality, form, context, function, rhetoricity, composition all in their turn emerged as values against which the canon was known and figured in modern architecture and which then informed the historicity of the present. Considering this theme and its interaction in light of a raft of historically determined abstractions shows how historical and architectural (or artistic) knowledge interacted across the modernist century. If the presence (or recurrence) of the baroque in twentieth-century architectural culture has often been casually admitted,7 the following pages show that by considering the modern historicity of the baroque one can better appreciate a structural relationship between history and architecture that goes beyond the sheer persistence of certain concepts and precedents.

While architecture had long registered the significance of the ancient world and its enduring authority, as well as the discourse on origins that was central to architecture’s positioning of itself in history and tradition across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the modern construction of the baroque as an historical subject offered a privileged view on the artifice of history itself. It is only with late-nineteenth-century writing on the baroque, named as such, that an historicist view of architecture – but now historicist in the modern sense – emerges along with a capacity for prognostication that combined judgement of the past with prescriptions for actions in the present that were, themselves, seemingly authorized by history. Early in the nineteenth century, Hegel had already ensured that a notion of artistic progress had become inseparable from the concept of art.8 This left the nineteenth century with the question of whether thresholds in that process could be identified and judged as progressive or deleterious. Such terms as baroque, Spätrenaissance, mannerism and rococo became, then, part of a general mechanism to determine and debate architectural values on historiographical grounds, describing breakpoints and continuities, which in their reception into the field of ideas shaping modern architecture constitutes something of its image – and one that shimmers differently in 1880, 1945 and 1980.

Of course, the term “baroque” is famously ambiguous, balanced as it is between naming an historical epoch, a period style and its development, and an attitude or artistic comportment that has been asserted by some to be a potentiality in every age and culture.9 The baroque’s precariousness as a conceptual and historical category has remained prone to the vicissitudes of the architect’s approach and attitude to history and its activation in the present has been played out in debates around periodization, definitions of style, meaning, and historiographical agency in architecture. This has served to determine the availability and the contingency of the baroque and, more generally, a broader historical authority over modern architecture that consideration of the baroque helped to secure. The chapters of this book, however, show another and more fundamental precariousness: the overlapping stakes of the historian and the architect in the history of architecture.

The significance of the baroque is not only that it was once a style in need of a name and periodization but also that its perpetual re-evaluation implies participation in more complex historical structures of broader significance for modern architectural culture. Is the baroque, as Giedion suggests, already a pair to modernism because their respective experiments with form and space contrast so markedly with the dry academic classicism of the intervening period? Or is the baroque a first point of true historical difference from the present as we look back through a long modern era shaped by industrialization and reason?10 Did architecture advance from this moment, as the modernist apologist Emil Kaufmann suggested in the 1930s?11 Or did the end of the baroque age see it decline into instrumentalism, as such critics of modernism as Dalibor Vesely argued in the 1980s?12 The possibility of the baroque figuring in a simple use of the past as a repository of admirable buildings becomes more remote when the architect’s access to it, as a field shaped in history, is loaded with these intricacies. And since that past is subject to re-evaluation, as it surely is, the historian can be understood to offer new challenges to modern values that draw authority from historical narrative just as that same narrative is shaped through the historian’s work.

Baroque into Service

Over the course of the displaced century addressed in this volume, the baroque was used both to clarify and to critique the concepts, relationships and ambitions of modern architecture through its interactions with history. That these themes might over time have cast off their anchorage to the baroque in a shift from the general to the particular suggests its innate utility to modern thought rather than its importance for modern architecture per se. These concepts were by no means either predominantly historical (found in history) or historiological (concerning history), but rather demonstrate the work that historians, too, were undertaking to distil concepts drawn from all manner of (modern) disciplines in order to address a broad range of questions posed across the arts and humanities.13 Within architecture, one of the most important translations undertaken from the end of the nineteenth century around the concept and content of the baroque, concerns the historiographical accommodation of space, which more than any other historically legitimated value served to ground modern architecture conceptually. The idea that space is a quality of the senses is, though, at base psychological, arising from the work of Adolf Hildebrand and, later, Theodor Lipps.14 It may have been a subject of architectural theory as early as the eighteenth century in the thinking of Etienne-Louis Boullée, but it took a fresh centrality in the writing of Gottfried Semper, August Schmarsow, Alois Riegl and, most famously, Sigfried Giedion, in whose hands space came to be treated as a medium proper to architecture as an art.15

The baroque figured productively in the coincident disciplinary rise of psychology from philosophy of mind and of the history of art and architecture, framing both a subject of study and an historical repository of modern problems. Thinking around the relation of sight to bodily extension shaped, for instance, Schmarsow’s understanding of the spatial experience of the walking subject and ultimately found its most profound modern expression in Le Corbusier’s promenade architecturale. In the positioning of the subject and the directing of its view, and through illusions dissociating vision from bodily extension, the baroque and its theatricality provided a wealth of examples of spaces that could not be explained as volumes, but which instead required a notion of subjective experience....