- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Little magazines made modernism happen. These pioneering enterprises were typically founded by individuals or small groups intent on publishing the experimental works or radical opinions of untried, unpopular, or underrepresented writers. Recently, little magazines have re-emerged as an important critical tool for examining the local and material conditions that shaped modernism. This volume reflects the diversity of Anglo-American modernism, with essays on avant-garde, literary, political, regional, and African American little magazines. It also presents a diversity of approaches to these magazines: discussions of material practices and relations; analyses of the relationship between little magazines and popular or elite audiences; examinations of correspondences between texts and images; feminist modifications of the traditional canon or histories; and reflections on the emerging field of periodical studies. All emphasize the primacy and materiality of little magazines. With a preface by Mark Morrisson, an afterword by Robert Scholes, and an extensive bibliography of little magazine resources, the collection serves both as an introduction to little magazines and a reconsideration of their integral role in the development of modernism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Little Magazines & Modernism by Adam McKible, Suzanne W. Churchill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Publishing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Negotiations

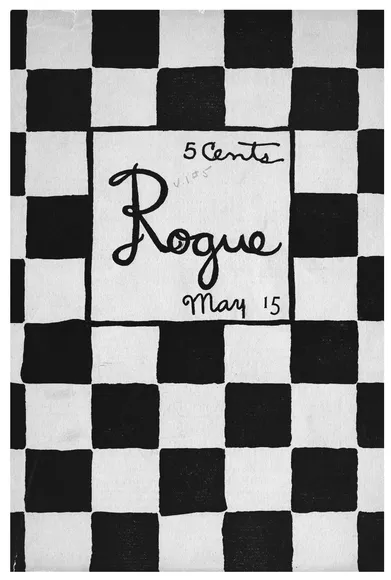

Fig. 2: Cover, Rogue, May 15, 1915. Archives & Special Collections of the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

Chapter One

Lines of Engagement:

Rhythm, Reproduction, and the Textual

Dialogues of Early Modernism

Faith Binckes

The publication upon which this chapter will focus is Rhythm (1911-1913), a British little magazine that has not always fared well in the authorized version of modernist literary history.1 It was conceived by its original editors, John Middleton Murry and Michael Sadleir, as "the Yellow Book of the modern movement" and offered a similar mixture of fiction, poetry, illustration, and reviews.2 Beside Murry and Sadleir. later in its run it published work by Ford Madox Ford. D. H. Lawrence, and Rupert Brooke. Katherine Mansfield made her initial appearance in the number for Spring 1912, became co-editor in July, and published extensively from that point on. It supported a group of young French writers, the Fantaisistes, printing not only their work but their views on the state of contemporary French literature. It was also perceived as "an artist's magazine"—"the organ of Post-Impressionism."3 While reproducing images by Picasso. André Derain. and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. the core of its striking graphic work was supplied by a group who took their name from the magazine's title: the Rhythmists.4 They assembled around the Scottish painter J. D. Fergusson, and adopted a style that drew upon and adapted, the Fauvist idiom of brilliant colors and bold delineation of form.

But despite its credentials, reading Rhythm with the view that the defining moment in the twentieth-century British avant-garde was the publication of BLAST three years later has led some commentators to dismiss it entirely—it didn't "catch the spirit of the cultural revolution that was in the air" in the period before the First World War, it was "only mildly revolutionary."5 Much of this criticism evolves from the fact that it did not issue a "proper" manifesto. Yet it requires only a small shift in critical perspective to reverse this pre-set lens and use the magazine to interrogate the wider movement. As we shall see, this re-reading indicates an avant-garde conditioned by the need to generate and secure cultural capital, by particular and often competitive dialogues, by negotiation and engagement as much as revolution and rupture. Some of the most significant of these dialogues evolved from the "multifarious literary interrelationships" intrinsic to Rhythm's position as an illustrated, periodical text operating within a distinct and unstable literary field.6 In this article I will be looking at one particular angle that acts as a focus for many of these issues: the role of material, cultural, and—to a certain degree—sexual (re)production in the magazine's early numbers.

Rhythm's first engagement was with terminology. In his autobiography, Murry suggested that he had been given the idea for the magazine, and for its title, by Fergusson when the two of them met in Paris in 1910 and discovered a shared interest in Bergson's theories of time, duration, and élan vital, "one word was recurrent in all our strange discussions—the word 'rhythm.' We never made any attempt to define it ... All that mattered was that it had some meaning for each of us."7 Murry claimed to have been equally affected by Fergusson's energy, his sincerity, and his determination to connect philosophical discourse and artistic practice—all elements that could be drawn together under the same authenticating term. Fergusson was the genuine article precisely because he "lived in a rhythm of his own, and it was a real rhythm."8 What Murry omitted from this retrospective account was the popularity that the idea of rhythm possessed. His private dialogues with Fergusson might indeed have invoked an intuition that struggled to formulate itself in language, but that invocation was operating very visibly in the wider public sphere. According to Frances Spalding. "'Rhythm' denoted modernity at this time." and there was already a magazine in Paris with the same title.9 Murry was not the only newcomer to the literary field to realize its potential. In his early writings for Poetry Review, Pound played upon a similar point. Just as Murry would later describe Fergusson as the true artist, living in "a rhythm of his own." Pound in 1912 claimed "rhythm" as the hallmark of the true poet—"uncounterfeiting and uncounterfeitable."10 A further perspective is provided by contemporary art critic Frank Rutter, in his memoir of the period:

RHYTHM was the magic word of the moment. What it meant exactly nobody knew, and the numerous attempts at defining it were not very successful. But it sounded well, one "knew what it meant", and did not press the point further. When we liked the design in a painting or drawing, we said it had Rhythm.11

Rutter's statement adds an illuminating, if highly pragmatic, gloss to Murry's recollection of the difficulty in defining rhythm, by observing that this indeterminacy—far from being a drawback—was one of the things that made the word tremendously useful. When one wanted to stamp approval upon a particular work of art, one said "it had rhythm." As such, while far from meaningless, as a term it had another important function—it could be used to designate value. It is this connection between the agreed plasticity of "rhythm." notions of value, and the distance between 1911 and 1914, that allows Rhythm's lack of a BLAST-style manifesto to be read in a different light. For a start, if we take to heart Janet Lyon's suggestion that manifestos should not be defined according to an overly restrictive model, then Marry's early editorials in Rhythm should be included.12 While these laid out the broad ambitions of the magazine, like many manifestos their effect was as performative as it was prescriptive. That is, they advanced a language—linked to rhythmic. Bergsonian individualism but also to Murry's recent reading of Hegel—through which the new work that appeared in the magazine might be digested and approved. Conspicuously, Murry dismissed as illogical the idea that artistic progress could be made without some sort of dialogue with the past, and set up the intuition and intelligence of the artist as a guarantee that this engagement would not result in mere reproduction:

[Art] seeks an expression that is new not merely because for generations there was nothing, but new because it holds within itself all the past. The artist... must identify himself with the continuity that has worked in the generations before him. His individuality consists in consciously thrusting from the vantage ground that he inherits; for consciousness of effort is individuality ... In truth, no art breaks with the past. It forces a path to the future.13

But for Murry as a little magazine editor, this flexible form of authentication had other benefits. George Bornstein's observation that "the notion of 'intention' itself tends to dissolve under examination into a bundle of different intentions that may be in harmony but may also be at cross-purposes and contradiction with each other" is particularly applicable to the composite, hybrid little magazine format.14 The near impossibility of assembling a collection of texts and images that appeared periodically and conformed to a single, fixed aesthetic blueprint was certainly an issue for the affiliation of artists and writers brought together by Murry and Fergusson.15 Furthermore. Rhythm was competing for position within the messiness of an uncertain present: "Si nous sommes à la veille d'une renaissance." Francis Carco wrote in Rhythm in November 1912. "il n'est pas tres facile de prevoir comment cette renaissance se développera."16 Deploying the culturally privileged but sufficiently fluid terminology of rhythm permitted Rhythm tO negotiate such uncertainties, and to theorize its project in a manner sympathetic to the conditions of its production. And Carco's comment draws our attention to a final element worth considering when we think about the role of a certain kind of manifesto in the history of the avant-garde in Britain—the status of Futurism. Despite its undeniable influence, particularly on the format of BLAST, at this point Futurist textual practices were not the only option available for an ambitious little magazine. Indeed, by mid-1912, manifestos were such an immediately identifiable Futurist effect that other groups would have been well advised to look elsewhere for forms and terms with which to assert the credibility of their project. And here, "rhythm" continued to fit the bill. In sharp contrast to Futurism's fascination with self-manufacture, the difference it signified constructed authenticity in completely the opposite direction—through the very absence of a program, through its connection with intuition and through the adaptation of the artistic advances of the past. As Lawrence Rainey has observed, in the wake of Marinetti's high-profile London appearances, Pound's earliest representations of Imagism also went out of their way to emphasize the non-programmatic nature of the "youngest school here that has the nerve to call itself a school." generating, in Rainey's phrase, "the first anti-avant-garde."17 Yet "anti-avant-garde" is perhaps misleading, in that it respects the Futurist claim to avant-garde supremacy as closely as it critiques it. While Pound was undoubtedly highly conscious of Futurism, these writings—like those of Murry in Rhythm— were not only responding to its strategies, but participating in a different tradition of authenticating the new.

As the savvy Carco understood very well, how the modernist "renaissance" would develop within the little magazine field had a lot to do with who would succeed in establishing this sort of cultural capital, rather than who would win the battle for higher circulation or sales. Rhythm's most significant competitor here was a formidable one: the New Age under A. R. Orage. Both Murry and Mansfield had strong connections with the older publication. It had helped to launch Mansfield in 1910, had published the stories that would later be collected as In a German Pension in 1911. and had printed several articles by Murry. Huntly Carter, its art and drama critic, was also a committed supporter of Fergusson. A publication that thrived on debate and controversy, the New Age was never going to accept Rhythm's appearance gracefully, but the particular terms it deployed to devalue the magazine generally constructed its own idealized image by opposition. This is nowhere more apparent than in an exchange concerning an act of reproduction: Rhythm's decision to include an image by André Dunoyer de Segonzac. entitled Les Boxeurs, another version of which had appeared in the New Age earlier in the year.

De Segonzac was a friend of Fergusson's—the two of them had taught together at the Académie de la Palette from around 1907.18 An experimental artist who retained an enthusiasm for the figurative, in 1910 De Segonzac had published two albums of drawings of Isadora Duncan. Around the same time he started attending boxing matches, Les Boxeurs being a product of this period. In the painting, inhumanly elongated figures advance upon...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction

- PART I: Negotiations

- PART II: Editorial Practices

- PART III: Identities

- Appendices

- Index