1 | Climate smart agriculture |

| Is this the new paradigm of agricultural development? |

| Udaya Sekhar Nagothu, Solveig Kolberg and Clare Maeve Stirling |

Introduction

Climate change poses a major threat to humanity and is likely to exacerbate political and economic instability in many countries as tensions fuelled by food insecurity rise. By 2050, climate change is expected to impact negatively on more than half of all food crops in sub-Saharan Africa, and at least 22% of the area cultivated by the world’s most important crops, most notably rice (Campbell et al., 2011). This is against a backdrop of a rising global population that is predicted to reach 9 billion by mid-century, requiring a 70% increase in global food production (Miller et al., 2010; FAO, 2013). Some would argue that adaptation strategies that focus on increasing food production are misled because there is already sufficient food produced to feed more than the projected 2050 global population. Instead, the focus should be on creating equitable and efficient food systems that are sustainable and provide secure access for all (Holt-Giménez and Altieri, 2012; IAASTD, 2008). This includes addressing losses and waste in the food chain that result in as much as one-third of global food production not being consumed. The ambiguity over whether to produce more food or not, has whipped up a serious debate amongst the different groups who view the issues of food insecurity through their own ideological lenses. The fundamental question is, what kind of agricultural development is desirable and just to feed the world in the future?

Paradigms of future agricultural development need to balance growth with environmental sustainability. According to proponents, climate smart agriculture (CSA) is one such approach that aims to address the challenges of food security and climate change by sustainably increasing agricultural productivity whilst adapting to climate change and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (FAO, 2011). A differentiating aspect of CSA is the notion that agriculture has a huge potential to mitigate climate change by reducing GHG emissions and sequestering carbon in soils. Those in favour of CSA argue that if soils can be used to fix carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, then they can generate carbon credits that can be sold to polluters who want to offset their emissions. That said, there has been heated debate recently about the mitigation potential of certain agricultural practices (Neufeldt et al., 2013) with the general consensus being that practices such as no-tillage have a limited ability to sequester carbon in the soil (Powlson et. al., 2014). Environmentalists argue that carbon markets generated due to CSA will only serve the corporate sector and marginalise smallholder farmers further. Therefore, an important question is, whether the ongoing debate on climate adaption, mitigation and food security is helping smallholders and the environment in any way.

The sustainable development model that evolved from the environmental movement recognised the need to limit growth but managed to avoid the conflict that exists between continued growth and environmental sustainability by reframing the economic objective as ‘development’. A more mainstream model is that of ‘Green Growth’ or ‘Environmental Keynesianism’ which not only insists on the compatibility of growth and the environment but also argues that protecting the environment can actually stimulate better growth. Blackwater (2012) believes that all these paradigms are fundamentally flawed and that ‘Green Growth’ depends on the consumer economy that in turn relies on continuous economic growth that is damaging to the environment. Environmentalists, on the other hand, propose to reduce consumer demand and halt the promotion of endless growth which Blackwater (2012) argues may be good for the environment but is economically untenable. There are other concepts such agro-ecology and food sovereignty that are gaining momentum and do not prefer to be associated with CSA. Their main criticism is that CSA does not have as developed a set of approaches as agro-ecology. The role of corporations, governments and scientists in deciding what is CSA is currently under political contestation. CSA needs to be attentive to ecological limits and social inequities as well as clarify the specific practices associated with the term and recognising the trade-offs and limitations (Harvey et al., 2014; Neufeldt et al., 2013). Some realignment of development paradigms will be required to generate new models of agricultural development that involve some form of socialised investment, with social equity and environmental sustainability as the main objectives, rather than a purely profit motive (Patel, 2009; Patel, 2012).

Is CSA then, the new Holy Grail of agricultural development, as some scientific groups claim? According to Neufeldt et al. (2013), CSA may have the potential to establish the climate change-agriculture nexus. Many in the scientific community consider CSA as a strategic tool to leverage support and investment from policy makers, donor agencies and the private sector (CCAFS, 2014). As a relatively new concept, CSA has become relatively popular in the international community (FAO, 2009a, FAO, 2009b), although it has been criticised for being too all-encompassing and lacking an adequate scientific evidence base. Many CSA interventions are highly location-specific and knowledge-intensive and it will require considerable effort to develop the knowledge and capacities needed to make CSA a reality and to develop local specific CSA measures that are socially and environmentally acceptable and sustainable (FAO, 2013).

As scientists, we need to ask ourselves, what does CSA or for that matter any new agricultural paradigm really mean to a smallholder remotely located? During a visit to a coastal village named Rang Dong in Nam Dinh province in January 2015, we asked a farmer ‘What is your main concern right now?’ The farmer’s response was unsurprising, ‘the increasing salinity levels affecting my rice crop.’ Salinity levels are increasing each year in Vietnam due to seawater intrusion along the coast. Like millions of other farmers in the Red River Delta or the Mekong River Delta in Vietnam and other such vulnerable regions across the world, farmers are desperately looking for crop varieties and technologies adaptable to extreme weather and climate. Whilst adaptation to extreme weather is a priority of the smallholder, GHG mitigation will rarely be a deciding factor unless there are co-benefits such as increased profits. What, in an overarching sense, should scientists then be developing to make the new agricultural approaches more meaningful to millions of smallholders and the environment?

This book will attempt to address some of these thought-provoking questions and search for suitable answers that will contribute to the ongoing debate and knowledge development process at large. The multidisciplinary approach reflects the need to address different biophysical, social and institutional aspects of adaptation in order to develop the most suitable interventions to address the complexity of climate change. In this chapter, we present the conceptual framework and the need for more clarity in the concept, discuss the different components or key elements desired for ensuring successful implementation of CSA, highlight the opportunities, as well as gaps and limitations and finally provide some concluding remarks.

New paradigms of agricultural development

Climate Smart Agriculture

The FAO coined the term CSA in 2010 for the first time in the background document prepared for The Hague Conference on Food Security, Agriculture and Climate Change. Here, CSA was defined as: ‘agriculture that sustainably increases productivity, resilience (adaptation), reduces/removes GHGs (mitigation), and enhances achievement of national food security and development goals’ (FAO, 2011). The notion was that the agriculture sector needed to become climate-smart in order to reach the sustainable agriculture and rural development goals which, if achieved, would contribute to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of reducing hunger and improving environmental management (ibid.). The FAO and the World Bank have principally led the further development and use of the concept, while the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) has taken the scientific lead (Scherr et al., 2012). The concept has evolved since then from one that attempts to set a global agenda for investments in agriculture research and innovation to one that aims to benefit principally smallholders and vulnerable people in developing countries (Neufeldt et al., 2013).

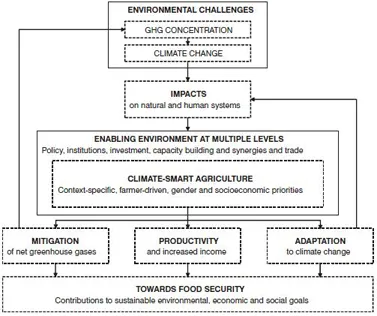

The CSA concept by definition envisions a transformation of agriculture systems to achieve short-and-long-term agricultural development goals that integrate the three dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social and environmental) by simultaneously addressing food security and climate challenges (Branca et al., 2011). The CSA perspective acknowledges agriculture’s contribution to global GHG emissions as well as its vulnerability to climate change. It is now built on three main pillars similar to the above definition, includes income and separates adaptation from resilience (FAO, 2013) thus aiming at: i) Sustainably increasing agricultural productivity and incomes; ii) adapting and building resilience to climate change; and iii) reducing net greenhouse gases emissions, where possible. Figure 1.1 shows a proposed framework for CSA illustrating the main components and inter-linkages needed to achieve the desired outcomes.

Figure 1.1 Framework for climate-smart agricultural landscapes

Policy, institutions, synergies and trade-offs, investments and capacity building, besides technologies, make up a crucial part of the enabling environment that could help to integrate CSA into strategies and plans at regional, national, and local levels and across landscapes. At the same time, CSA needs to be locally specific, farmer-driven and socially equitable. Integration of these priorities at different levels is critical for the success of CSA. The relative importance of the three main CSA elements (adaptation, mitigation and productivity) depends on the local context and stakeholder preferences and need to identify potential synergies and trade-offs (Campbell et al., 2014). The mitigation and adaptation components1 are both considered climate-risk strategies, and the two components also address the efficiency of production, i.e. sustainable increase in agriculture yields and income. Mitigation here is primarily co...