![]() PART I

PART I

PRELIMINARIES![]()

1

The Need to Redefine the Christian Image

Painting is dignified by age, it is distinguished by antiquity, and is coeval with the preaching of the Gospel … these sacred representations, inasmuch as they were tokens (sumbola) of our immaculate faith, came into existence and flourished as did the faith from the very beginning; undertaken by the apostles, this practice received the approval of the Fathers. For just as these men instructed us in the words of divine religion, so in this respect also, acting in the same manner as those who represent in painting the glorious deeds of the past, they represent the Savior’s life on earth, as it is made manifest in evangelical Scripture, and this they consigned not only to books, but also delineated on panels …1

These words of the Iconophile Patriarch of Constantinople (758–828), Nicephorus, were written in the midst of the second Iconoclasm in Byzantium. They were meant to persuade among others the Emperor Leo V not to banish painted images from worship. Considered from an aesthetic point of view, they carry a strange irony. They justify the existence of the Christian image by effectively undermining its art. Pictures are treated like words. They resemble documents and testaments of faith. To paint a picture of Christ is to declare that he is a real person, an incarnate God. To point at countless portraits of him is to prove that the need to depict his life is as natural and legitimate as the need to describe it. Those who love God want to see God and show him to others. The Patriarch opposed Iconoclasm but not its simplistic view of images. The Iconoclasts saw icons as little more than talismans and idols; their opponents, as little more than confessional instruments and symbols of devotion.

Yet, when Iconophile tracts like St. John Damascene’s apologia for images, describe intense visual and emotional responses to icons encountered in churches and dreams, an entirely different view of the image emerges. Here icons come to life. They exist on the verge of speech. They overflow with expression. They are as vital as apparitions. Was this mere rhetoric? Or was it also a way of conveying an aesthetic reality? Were religious and aesthetic experience somehow intertwined in a way that the Byzantines could not discern? Was their rhetoric the outcome of an astute aesthetic perception, a fusion of theology and form? The defense of images was a doctrinal affair and the priorities were clearly set. These “aesthetic” moments were quickly overshadowed by arguments aiming to show the absurdity of accusing the defenders of icons of idolatry.

In many ways, little has changed since. Weaved into the long history of the image in Christianity, the irony of Nicephorus’ defense has become almost invisible, its form hard to discern beneath the patina of praise and adulation layered on Christian art for centuries. Today, Christian theologians and hierarchs may speak the language of art criticism and history but they have little to say about the Christian image as an aesthetic object. Beauty is a favorite concept but it is rarely used critically. In theological studies, it is treated as a metaphysical concept, a transcendental when applied to God and being, a universal when predicated of sensible things. But its use with reference to the art object itself is often metaphorical rather than descriptive.2 Theological aesthetics works with the tension between supersensible and sensible, transcendent and immanent, but its principal subject is theology not art.3 It is not interested in the aesthetic object itself, the plastic existent put forth by the work of art. There is little interest in how beauty is associated with the presence of holiness in things and persons. Particularly where theology tries to engage postmodern thought, the beautiful is an occasion for taking flight from the world rather than dwelling in its being or actuality.4

This is a book about a type of Orthodox image that embodies and realizes deified existence aesthetically. Images of this type bring what they present to a state of temporal realization, as if in showing it they are bringing it into existence and keeping it alive and present in time. But they also invite a comparison to persons because like human beings they are capable of self-presentation and enunciation. Aesthetic objects with these qualities exist also in Modernist art and in the Ch’an (Zen) schools of Buddhism but not with the same modality as their Christian equivalents. They are aesthetic beings par excellence, exemplary images.

We take the aesthetic to mean what its name suggests: that which has sensuous form as the manner of its existence. It is common today to approach the aesthetic as the converging point of multiple rationalities that take charge of the art object to pluralize and disperse it in meta-aesthetic narratives.5 Often it is treated as a category that is irretrievably lost. Various ploys of rediscovery and substitution are proposed. Rhetorical exercises are devised in order to deconstruct it and find something inside, some sort of remnant or echo of a once real being. In my view, the aesthetic is that which presents itself as an aesthetic being or reality (on aesthetikon). All that we can say about it lies in this form of existence.

When one can see tension or fragility in the way that a line is drawn, one is in the presence of an aesthetic being. When a face is painted in such a way that it seems to withdraw itself from view, it exists as an aesthetic being. It is not just a picture or a work of art. It makes itself seen and noticed by virtue of its act of being itself: being a fragile line rather than one that conveys solidity (or resilience). This kind of aesthetic existence can reach different levels of complexity. When it thoroughly permeates an image, it sets it in motion. By subsisting in an act of self-expression and self-realization, it ceases to be a mere likeness and becomes a living thing, a life-form in art. It is then exemplary.

Exemplarity is in this sense the fulfillment of art (the perfection of its being). When in a picture we meet figures which stand in contained rupture, which speak through their silence, or move toward the viewer as if to open themselves to view (and yet not completely), we know right away that we are in the presence of something that commands its own reality. In that moment, it is hard to speak of an aesthetic of absence or similitude. It makes little sense to interpret or analyze the image because it speaks for itself. This is something that Chinese painters and critics, as we shall see, have known for centuries.

Icons with these qualities have always existed in the Eastern Church alongside those that seem motionless and devoid of expression. Noticing them often requires putting aside their devotional history or miraculous power (or our assumptions about “icons” and “Byzantine art”) and instead engaging them directly for what they are. This is a relationship to the image that photography can sometimes enhance as it may draw an icon out of its ornate and precious encasing and by focusing on the painting itself, discover qualities that would otherwise have been overlooked.

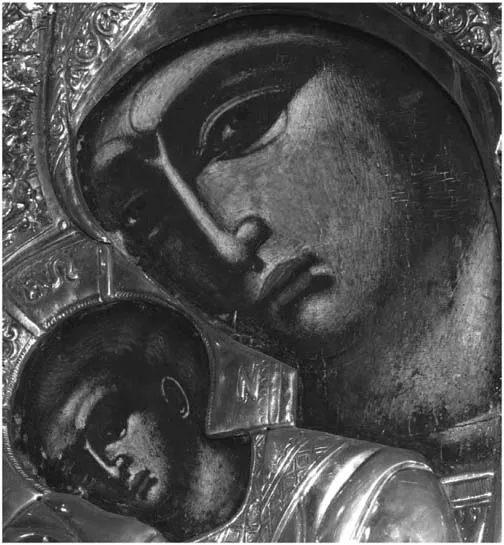

Figure 1.1, a photograph of the miraculous icon of the Panagia Dexia is a copy of a celebrated sixteenth-century Cypriot original (Panagia of Kykkou) that was offered to the Byzantine church of St. Hypatius that stood on the same location. “Dressed” in silver, it appears smaller in scale when seen with the naked eye. It is here significantly enlarged. Expressions of austerity and tenderness but also detachment and sadness are drawn on the faces of the two figures. The use of bold, thick lines to carve out their features especially around the eyes gives them a distant and yet dramatic presence, a quality of stillness, energy and pensive tranquility in which emotion is at once released and restrained.

1.1 Panagia Dexia (detail), undated, Church of Panagia Dexia, Thessaloniki, Greece

In the next photograph (Figure 1.2), the Saint’s intense and somber expression cuts through the blurring effect of light and motion. Tucked inside its silver “shirt” (hypokamison), the austere face seems absorbed in an act of grasping and arresting whatever may transpire in front of it and beyond it, in a space that is at once intimate and indefinite. Behind the glittering silver and gold and the flickering oil lamps and candles, the image posits its own reality, keeping watch of its own time. It makes itself present.

1.2 St. Marina (detail), undated, Monastery of St. Marina, Andros, Greece

Photography can bring to the icon the selective vision of its lens which impresses on the image the view of the one who photographed it. But it can also open the image to its own reality by capturing its visual life. Not all icons are receptive to this approach that we may call an act of “awakening” the aesthetic object. It takes an exemplary icon to do this or at least an image in which we can see elements of enargeia, an expressive frequency that photography may help underscore or make focal.

Enargeia is usually translated as vividness. Where it is present, something in the art object moves or comes alive. There are Zen paintings that also have this quality, even though their type of enargeia and that of the exemplary Christian image differ. The word, as we shall see in Chapter 3, has a long history. It is used, among others, by Plato in the Ion (535bc) to describe the coming alive (ephallomenon, ekphane, ekcheonta) of a Homeric character on stage in an act of divinely inspired impersonation. Enargeia brings to the art object the dynamism that is implicit in the concept of hypostasis. The image exists or actualizes its own being. It brings something of itself out to view, as if to show it.6 It “asks” to be treated as a part of life rather than its detached copy. In a Christian world, where things participate in the being of God, the image too is a participant. It has grace. If the image is Christian ontologically, it must, somehow make this visible.

The Christian image has always been seen as a participant in divine life but not in this aesthetic sense. Icons of Christ, the Virgin Mary, martyrs and saints secrete their blessings and perform miracles. The tradition dates back to the Edessa Mandylion, a piece of cloth on which according to legend Christ impressed his face—known later in the West as the Veronica (vera icona or true image).7 Like other images made without human hands (acheiropoietai), the Mandylion type legitimized Christianity’s ambivalent relationship to art.

Over time, the miraculous act of self-depiction carried a mandate for reproducing the divine likeness in physical objects by human hands. It established an aesthetic of verisimilar presence and apparitional realism that emphasized intimacy with a divine original. It focused Christian vision on...