![]()

Part I

Mapping Methods

Systems, Approaches and Innovations

![]()

1 Mapping the Emotions of London in Fiction, 1700–1900

A Crowdsourcing Experiment

Ryan Heuser, Mark Algee-Hewitt, Annalise Lockhart, Erik Steiner and Van Tran

Introduction

How does literary geography change as it becomes digital? In the new spatial humanities, the turn towards digital methods offers both greater scale and precision, creating opportunities to study new kinds of critical objects. A concept such as Matthew Wilkens’s ‘geographic investment’ (the number of words in a text naming particular places) is made possible by our ability to algorithmically identify and count place-names within a large literary corpus (Wilkens 804). Such a concept is radically new to literary studies and, we argue, important for understanding the complex relationship between fiction and its represented geography, as it allows macroscopic literary-geographic patterns to emerge. However, although the identification of text’s geographic investment requires an algorithmic approach, such an approach is unable to parse the meaning of the patterns it identifies. Without knowledge of the ways places were invoked in fiction, maps of general geographic investment are, to a certain degree, intractable to interpretation.

A computer cannot add meaning to place; it can only count place-names. In the foundational works of literary geography, such as Franco Moretti’s Atlas of the European Novel and Barbara Piatti’s project A Literary Atlas of Europe, the advantage of the spatial turn lies in the critic’s ability to uncover the nuanced relationship between spatial pattern and textual meaning. What is needed, we argue, is a synthesis of these methodological innovations: the ability to uncover geographic information on a significantly new scale whilst at the same time preserving our ability to understand how each place functions within its unique textual environment. Our goal in this project is to put the computational logic of Wilken’s geographic investment into contact with the detailed geographical hermeneutics practised by such critics as Moretti and Piatti, so that we can interpret the meanings of places in fiction across thousands of texts.

This chapter is a record of one such attempt at contact, mapping eighteenth- and nineteenth-century novels’ affective investments with places in London.1 During this period, London’s unprecedented expansion fundamentally transformed its social organisation, a transformation deeply imbricated with the contemporaneous rises of the bourgeoisie, literacy, the publishing industry and the novel (Moretti, The Bourgeoisie; Barker 52–4; St Clair; Watt). In mapping the ways in which the novel affectively imagined the city at the heart of its own British publication, we hope to construct a geography of London that makes visible these reflexive, literary-sociological ‘structures of feeling’ (Williams 132; Porter 35). Drawing on the affect-theoretical work of Paul Fisher and Sianne Ngai, we attempt to operationalise the idea that emotions can act ‘as a mediation between the aesthetic and the political in a nontrivial way’ by mapping fiction’s affective engagements with real places in London onto the city’s own evolving urban landscape (Ngai 3). In this way, we hope to bring literature into spatial contact with aspects of its own social organisation, superimposing fiction’s qualitatively distinct affective representations onto the quantitative dimensions of geographic space and historical sociological data. We believe that digital literary geography can thus provide an important and productive deconstruction of what James English has called ‘the false but pervasive perception of a great divide between literature and sociology, with the former all irrational devotion and interpretative finesse and the latter all scientific rigor and verifiable “results”’ (xiv). Without conflating them, or subordinating either to the other, such a geography quite literally creates a space in which concepts of literary form and social forces can meaningfully cohabit.

In the following two sections, we present two distinct phases of our project’s methodology. In the first, we use predominantly computational methods to measure novels’ geographic investment with London through their explicit mentions of known place-names. In the second, we leverage emerging techniques in crowdsourcing to distribute the reading and annotation of passages mentioning London places, in order to gather a readerly consensus on two ways in which each place functions within each passage: (a) whether the passage is set in the place; and (b) whether a particular emotion is associated with the place.

Geographic Investment in Fictional London

Methodology

Mapping a text’s geographic investment consists of mapping the known place-names it mentions; however, we recognise that place-names do not exhaust a novel’s relationship to place. Novelists of both the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries employed a wide range of obfuscatory techniques when mentioning a setting’s location, such as Austen’s shortening of English shires to ‘——shire’. Moreover, settings were often not explicitly related to geographic space at all (Piatti 184). These alternate spatial practices, however, only highlight the specificity and intentionality of an explicit place-naming practice in fiction. Place-names, we believe, do important fictional and cultural work, suturing narrative and geographic space whilst also calling upon and contributing to connotations that have accrued through wider cultural circulation.

The corpus of fiction in which we investigated London place-names derives from the Literary Lab’s fictional corpus, which extends through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and derives from a variety of sources.2 Filtering to include only works of English-language fiction first published between 1700 and 1900, and which were digitised accurately enough for 90 per cent or more of its words to be recognised in a dictionary (representing its OCR accuracy), we were left with exactly 4,862 texts.3 To find passages in this corpus mentioning London places, we developed a hybrid methodology that combines current techniques in computational toponym discovery with a traditional research-based approach. Although Named Entity Recognition (NER) software is a staple of current digital literary-geographic research, most NER packages are trained on contemporary journalistic sources and lack the precision required to recognise many specific locations in historical London (Manning et al.; Finkel and Manning). We therefore decided to supplement the results from an NER analysis of our corpus with historical gazetteer research into a variety of digital, print and map-based resources (Jackson; Paterson; Matthew). From a compiled list of 382 locations, we chose 161 to investigate for this chapter, in an attempt to represent the most frequently mentioned places as well as to retain a spatial representativeness over the wide extent of London.4 Our list is certainly not exhaustive, but we believe that, given the multiplicity of its sources and sampling methods, it is broadly representative of the most salient locations of the period.

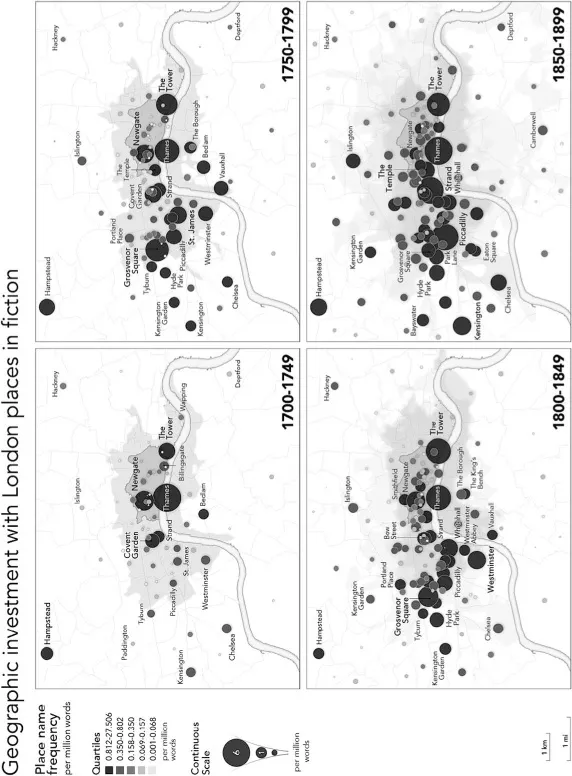

However, due to the ambiguity of place-names – ‘the Tower’, for instance, does not always refer to the Tower of London, nor ‘Richmond’ to the London suburb – it was not enough to simply rely on algorithmic counts of place-name mentions. We decided to generate a random sample of passages in which each place-name occurred. Dividing the two centuries into four half-century ‘periods’, we read through the generated passages per place, annotating whether it (e.g. ‘the Tower’) actually referred to the place in question. We continued this process until we identified at least ten such legitimate passages per place, per period, to be used in the crowdsourcing experiment of section 3. From these annotations, we were also able to estimate how often each place-name legitimately refers to its place in a given half-century of fiction. For instance, we estimate that ‘Richmond’ refers to Richmond the suburb about 60 per cent of the time in fiction published 1850–99.5 These likelihoods were then used as ‘scaling factors’, and were multiplied by the number of mentions of a given place-name in all the novels of a given period. For example, ‘Richmond’ occurs about 2,630 times in fiction published 1850–99, so we estimate that it actually refers to the suburb about 1,578 times, or 60 per cent of the total. These scaled frequencies were then normalised, divided by the number of all words in the novels of the respective half-century, in order to express the likelihood, per million words of fiction, of encountering a legitimate mention of each place in each period. These frequencies were then represented using GIS, through which we geographically encoded each place as a polygon extending over its visible boundaries on Charles Booth’s 1889 map of poverty in London. In certain cases, we draw a distinction between ‘buildings’, object-like places including buildings, streets and squares; and ‘districts’, area-like places including neighbourhoods and districts. However, in all but Plate 2, we represent the respective data as circles pinpointed to the centroid of the place’s polygon in order to provide comparability between places as spatially diverse as towers and slums. In Figure 1.1, both the size and shading of a circle symbolise the place’s frequency per million words in fiction of the period. Here, Booth’s map is made transparent, but the boundaries of our ‘districts’ are outlined for geographic reference.

Interpretation: Investment and ‘Stuckness’

In reviewing William Sharp’s 1904 map of the chief localities of Walter Scott’s novels, Piatti notes that these early maps of literary geography ‘succeeded [in visualising] a couple of important aspects’ of the emerging field, namely ‘the distribution of fictional settings (“gravity centers” vs. “unwritten regions”)’ (181). This tension between novels’ actual geographic investments and their unexplored possibilities seems especially evident in Figure 1.1. These maps pose an important question: were novels really invested in representing London as a whole, or just the City and West End? London grew in population from 600,000 to 6.5 million over the two centuries represented here, expanding far beyond the City’s historic walls and gates (‘Historical Census Population’; Thirsk 6). Fictional London, however, is remarkably concentrated. Broadly representing the most frequently occurring London place-names in our fictional corpus, this map reveals a deep-rooted ‘gravity centre’ in fictional investment centred on the point at which the City and the West End meet. In the process of remediating the city, London fictions distort its geography by compressing and centring it in the West. This concentration of attention is apparent even amongst novels published in the last half of the nineteenth century, at which point London’s urban development had already absorbed most of its outlying communities. Fictional attention, then, offers an alternate map through which we can understand the space of London, a map whose contours are only loosely defined by the contemporary urban geography of London.

Figure 1.1 Geographic investment with London places in fiction.

But to what extent should we expect this distortion, given London’s historical evolution? The City is, after all, the original extent of London, containing many of its most ancient and iconic locales: St Paul’s Cathedral, the Guildhall, Smithfield and Newgate, just to name a few. And it was only during the plague and fire of London during the seventeenth century that many aristocratic Londoners began to relocate from the City to newly built residences in the West End. Consequently, the West End still contains many of the most fashionable locales in London, as sites such as St. James’ Square organised a new, aristocratic and orderly social space in contradistinction to the piecemeal and mercantile space of the City (Black 118). In a way, then, the concentration of fictional attention reflects London’s actual social geography – but in its seventeenth century configuration, suggesting a kind of literary-historical ‘stuckness’. This stuckness manifests as a discontinuity between the place as it might have functioned in the wider geographic system of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century London, and the place as it would seem to function in the more concentrated geographic system of London’s fictional representation. It is as if this earlier configuration strengthens the capacity of these places to act as cultural symbols for readers of the text, functioning as a shorthand, replete with associations that have accrued through history.

In reality, London in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries expanded rapidly, dramatically transforming its two oldest districts – the City and the West End – from the city’s residential focal point to the commercial centre around which more populous suburban districts grew. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the residential population of the City fell from 129,000 to 27,000. Although the West End doubled its population from 231,000 to 460,000, t...