eBook - ePub

Dot Com Mantra

Social Computing in the Central Himalayas

Payal Arora

This is a test

Share book

- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dot Com Mantra

Social Computing in the Central Himalayas

Payal Arora

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Billions of dollars are being spent nationally and globally on providing computing access to digitally disadvantaged groups and cultures with an expectation that computers and the Internet can lead to higher socio-economic mobility. This ethnographic study of social computing in the Central Himalayas, India, investigates alternative social practices with new technologies and media amongst a population that is for the most part undocumented. In doing so, this book offers fresh and critical perspectives in areas of contemporary debate: informal learning with computers, cyberleisure, gender access and empowerment, digital intermediaries, and glocalization of information and media.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Dot Com Mantra an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Dot Com Mantra by Payal Arora in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Social Aspects in Computer Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Local as Celebrity

In a village in India, corporate-sponsored students ask the sarpanch, the village head, about computers, hoping to gain information on the needs of the villager:

At one point, one of the lead students asked: “What do you expect the ‘computer’ to do for your village?” The sarpanch answered: “We are not sure what ‘computers’ do, so we are not sure what to answer.” The student began to explain and suddenly, to our ears anyway, the room erupted into what seemed like all 30+ people – standing, sitting, hanging on in windows and open doorways – speaking simultaneously. At one point, several minutes into this, the other student, sitting near us leaned over and said, “this is getting out of control.” Then, just as suddenly the tumult quieted and the sarpanch indicated the room now understood what “computers” could do. They then proceed to provide excellent responses to the original question. (Thomas and Salvador, 2006, p. 112)

The miracle of the “local” has arrived; from supposed passive remote individuals, they are now viewed as receptive social collectives with shared knowledge, craving to chalk their path with new technologies. The local today enjoys celebrity status. In the last decade, corporations, states and transnational agencies alike have unleashed their army of ethnographers to unravel the mysteries of the local consumer, particularly in what is considered remote, disadvantaged and marginalized areas of so called Third-World nations as they interact with computers. India is one of their favorite sites as it serves as a “live laboratory” and potential market for new technology interventions given its Silicon Valley status. The new consumers within this laboratory are now seen as promising subjects that will engage and socialize with new technologies and “leapfrog” barriers of illiteracy, superstition and poverty to access and use these computer-mediated spaces for socio-economic mobility (Bhatnagar and Schware, 2000; Keniston and Kumar, 2004).

Yet behind these anecdotal celebrations, there is little understanding of this supposed leapfrogging: of how people in marginalized areas instruct each other and themselves about and with computers for varied purposes; of how people play with new technologies and navigate and circumvent such artifacts and its spaces to create potentially new forms of products, processes and practices; of people’s perceptions and beliefs of computers and its relation with other new and old technologies and its institutions as well the effect of past to current government policies and practices in technology dissemination for development on people’s receptivity and usage of computers. Such a focus on day-to-day learning is important if we are to genuinely de-romanticize and demystify constructs of deliverance and promises of computers as pathways to change.

In fact, every new technology gets caught up in the timeless debate of euphoric proclamations of its transformative capacities on social practice to foreboding condemnations of such technologies as oppressive, divisive, homogenizing and regulating of social life. Not surprisingly, in current times we are bombarded with a slew of optimistic discourse on the effects of the computer and the Net on social unison, mobility and democracy: the promise of the “information superhighway” (Cozic, 1996), “virtual communities” (Rheingold, 2000) and “netizens” (Hauben and Hauben, 1997). Simultaneously, there is a legitimate concern of participation within this digital sociality with emphasis on the “digital divide,” a perceived phenomenon of technological exclusion based on social, cultural, economic and other parameters (Warschauer, 2003). Hence, there is a need to provide a frame of reference from which to evaluate these various claims made about properties of a new technology, its novelty and its relationship with sociality at large.

Social Learning with Computers

This book investigates how and for what purposes do people in Almora, Central Himalayas, India, use computers and the Net in informal public venues. This is an eight month ethnographic work in Almora, a town of 56,000 people in Uttarakhand, Central Himalayas. This study focuses on relations between old and new technologies, how people harness physical, social, economic and cultural resources to facilitate their understandings with these artifacts, the nature and consequences of this learning as well as perceptions and beliefs about the artifacts – its situated spaces and activities within the larger context of development policy and practice. Investigating practices amongst a relatively remote and new group of users of the computer and the Net allows for possible new perspectives to emerge and perhaps old views to be reinforced and revisited. This work contributes to realms of user-interfacing, new media, information consumption and production, social learning with technology, ICT and international development and policy and practice of new technologies for social change.

The book moves beyond the hype of new technologies by delving into the spectrum of human imagination and enactments with computers and the Net. Technology can be viewed as an artifact and technique of human invention that shape and is shaped by social learning with often unpredictable consequences. Technology is seen as a material embodiment of an idea. What constitutes that idea depends on who and where it is framed and to what ends. Social learning is viewed as a dialectic process and enactment of human ingenuity. We cannot make meaning of technology without understanding its place and space, its boundaries, frames of reference, its coordinates of interpretation, functionality and optimization. After all, technology usage is a situated social practice. This study indexes technology in realms of a learning context, however temporarily so, to best understand its enactment.

Figure 1.1 Map of Uttarakhand, India

Source: Rajiv Rawat, www.uttarakhand.net

Almora town is situated in the Almora district of the Kumaon region in Uttarakhand State, Central Himalayas. It is “remote” in a sense of being eight hours away from one of the nearest cities, Delhi, and being relatively isolated in the mountains where households are scattered across hilly terrains making access and usage of goods, people and spaces a significant challenge. With 90 percent of its 632,866 population living in villages and surviving on subsistence agriculture, this area is looked upon as disadvantaged and marginalized and officially demarcated as “backward” (Sati and Sati, 2000). The town itself has around 56,000 people. Furthermore, with the formation of Uttarakhand as a new state in 2000 (carved out of Uttar Pradesh), an influx of national capital has come towards this region to develop it particularly through technology, earning the title of an “e-readiness” state (OECD, 2006). Hence, in the last five years, schools and universities have been provided with computers, with broadband entering this arena only in the last year or so. Besides this, public-private partnerships have blossomed to set up public venues for computer and Net access and usage for “economic and social mobility” of the masses (Garai and Shadrach, 2006). These nascent initiatives contribute to making Almora an interesting site of research.

The deliberate choice to investigate learning practices with computers outside school settings is primarily to reveal a wider perspective of education that is not hindered by chronic formal institutional difficulties. A good amount of research has gone into formal educational and technical failures including but not limited to poor connectivity, teacher training, electricity, software and hardware access and design, maintenance, lack of relevant content and more. Rather than continue to circulate such findings by following up with formal education’s limitations on learning, this study looks for alternative sites of engagement, in this case at cybercafés, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and government cyber kiosks. The rationale is that by looking outside school settings in public contexts where engagement does happen, much can be learnt about how people actually interact with these resources in the widest possible sense.

By focusing on the micro-politics of engagement through ethnography of new technologies, much can be revealed about the macro-political nature of technological intervention, mediation and human ingenuity with new tools and practices: how people talk about these new tools, what they say about it, to whom they talk about it to, why they choose to use it at specific moments in time and space, when they seek for it and when they disengage from it, how they relate past and ongoing practices with old and different technologies to these new tools, how they learn to reproduce, modify and transform events with these artifacts, where and how they position themselves and others in relation to these tools, why they choose certain spaces over others, are all factors contributing to the understandings of usage with computers and the Net.

By no means does this study intend to “cover” Almora in terms of representing it as a “local whole;” rather, creates a strategic coalescence of captured experiences and discourses of people using and being used by technology; perceptions to practices:

Although multi-sited ethnography is an exercise in mapping terrain, its goal is not holistic representation, an ethnographic portrayal of the world system as a totality. Rather, it claims that any ethnography of a cultural formation in the world system is also an ethnography of the system and therefore cannot be understood only in terms of the conventional single-site mise-en-scene of ethnography, assuming indeed it is the cultural formation, produced in several different locales, rather than the conditions of a particular set of subjects that is the object of study. For ethnography, then, there is no global in the global/local contrast so frequently evoked…The global collapses into, and made an integral part of parallel, related local situations rather than something monolithic or external to them. (Marcus, 1998, p. 83)

This pastiche allows for a glimpse of a range of usage regarding computers, through which we can gain insight into pertinent concepts of technological novelty and impact within larger contexts of international development and policy. Less attention is paid to who is seen to be on which side of the digital divide and more on how people, spaces, ideas, activities and tools come together in deliberate and strategic orchestrations for the enablement of the computing event.

Methodology

Eight months of fieldwork yielded a large body of data of which only a small fraction is delved into in-depth for the present discussion. In addition to field notes, an intensive analysis was made of all the literature produced and made available at the local level in the form of government documents and non-government organization (NGO) promotional literature and reports. At the same time, a wide range of material, relevant to the daily activities was amassed: drafts of articles, news abstracts, letters, photographs, emails, memos, and more. Formal interviews were carried out with a large number of people from teachers, principals, students, local government officials, swamis and sadhus, NGO founders and employees, villagers, youth, grassroots activists, local business people to farmers and traders.

Focused group discussions with farmers over week long periods across the duration of fieldwork added a significant dimension to this analysis. All such discussions transpired in Hindi. These interviews supplemented the vast body of comments and information gleaned during informal discussions. Surveys were conducted amongst youth from the urban to rural counterpart reflecting important patterns in perceptions and usage of computers.

Reflections through observation provided a further source of data. No attempt was made to conceal my role as a researcher. For example, when I interviewed people, the tape recorder was clearly present and publicly acknowledged. In group discussions, even when I took a backseat, the group was cognizant of my role as the researcher. In fact, I made it a point to give the participants the opportunity to question me on matters of their interest which did not limit itself to the topic at large. This allowed for mutual curiosity and interest to deepen and shift such interactions from an interview mode to that of a discussion. As with all ethnographies, key names, dates and places have been changed to protect the identity of those involved. In cases where people and institutions have been named, it is to pay my deep debt to them for their significant influence on my work as elaborated in the acknowledgement section.

I chose to be stationed for the duration of my fieldwork at Uttarakhand Seva Nidhi Paryavaran Shiksha Sansthan (USNPSS), a well established and reputed NGO committed to environment and education. This NGO was located in the town of Almora. However, given the past decades of outreach and capacity building, they had succeeded in nurturing ties with the most remote of villages. Using this as a base, I traveled to neighboring villages and towns for a good portion of the time (perhaps a third of the time) based on strategic opportunities and events that came my way. This back and forth between the rural and the urban area allowed for the juxtapositioning of practices and perceptions that was influential in the analysis of this work. Having such a base itself was a tremendous boon. By mere association with this respected NGO, I found people more receptive and open to questions. More importantly, the almost daily discussions with the staff and the founder who had invested a great portion of their lives to the development of this region, added a constant challenge and insight to day-to-day events.

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of my association with this NGO was its weekly training sessions with villagers from Almora and neighboring districts at large. The NGO made a concerted effort to get villagers to their NGO for training which included young girls as balwadi or pre-school teachers, farmer cooperatives to women groups for local elections, health and livelihood. Through my stay there, I met and lived in the same quarters with these people and thereby was able to have prolonged and deep discussions with them in less formal settings. Of course, there was always the need to be aware of the NGO’s own biases when interpreting such data. This tension of learning and yet disassociating from this organization was a constant struggle throughout my time there.

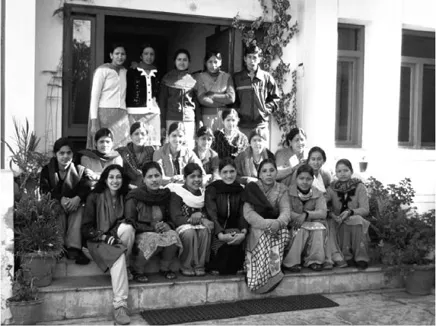

Figure 1.2 Researcher (bottom left) with Balwadi Teachers at USNPSS

So while the NGO provided a fertile ground to explore perceptions of villagers, the actual identification of computer usage took a rather different path. At the embarking of fieldwork, I was directed to “failing” technology initiatives: the famous Hole-in-the-Wall (HiWEL) experiment by NIIT (an Indian IT company) and the Soochna Kutirs, the Computer Information Centers (CICs) for economic and social mobility as part of the national digital equity drive. These two sites of low engagement form Part II of the book under “Computers and Rural Development,” followed by “Computing in Cybercafés” in the Part III section, the main sites for high public engagements with computers. To go more in-depth into the workings at cybercafés, I chose one cybercafé reputed to be the most popular. New arenas sometimes require new strategies of investigation. Given its limited space, I volunteered to work for free at the cybercafé during my stay there in exchange for being part of its activity. This action research posed a constant dilemma for me where I became complicit in activities, some of which can be deemed as “plagiaristic.” In addition, there was continued effort required to restrain from advising users at this café in their understandings and interpretations of online content.

As in any ethnography, trade-offs are many and dilemmas are aplenty. This study is no exception. The age old tension of breadth versus depth was encountered at the local arena as I chose to pursue multiple sites of engagement and discourse over delving deeply into just one site or issue. By being stationed at an NGO, there is no denying that some of the discussions encountered were colored by its larger ideology which perhaps was projected onto me.

This study offers a partial but important and unique perspective regarding computer usage, helping to challenge some popular notions on computing. It shifts some of the key debates and assumptions on computing: direct interfacing and empowerment, relations between online information and socio-economic mobility, the makings of knowledge and its relations to new technology, the ameliorative role of computers and the role of intermediaries and institutions in technology design, access and usage.

The emphasis on the social reveals my bias over that of a cognitive and quantitative kind. However, that can be said about all studies in terms of biases of a varied kind. In this case, we should look at such pursuits as extensions of other such discussions to form a composite understanding of practice. By association and intersection of these investigations, its complexity is revealed to give rise to better and more pertinent questions as well as fairer and more legitimate assumptions of practice. In other words, this work strives to humble large claims in policy and practice.

Techno-Revelations for Development Policy and Practice

This fieldwork with relatively new computer users at cybercafés has revealed that much of their computing activity is arguably non-utilitarian in an economic sense; instead, it is more centered on social and entertainment purposes. This has led to further the investigation in relations between labor, leisure and learning within transcultural and technologically-mediated environments. Also, for the most part, most of these users happen to come from the town versus the villages, although, as will be revealed, engagements come in multiple forms and through a range of critical intermediaries.

The encountering of high-profile national technology initiatives at the ground level has lent an important policy perspective to this study, demonstrating how these initiatives play out. In particular, social interaction with computers has been looked at closely as tied to two such projects: 1) Soochna Kutirs, ICT kiosks designed as digital “knowledge centers” for rural people as part of the Mission 2007 national policy initiative to connect 600,000 villages in India through computers and, 2) the HiWEL (Hole-in-th...