![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Jennifer Gunning, Søren Holm and Ian Kenway

Ludwig Feuerbach’s stark but truthful observation ‘Der Mensch ist war er isst’ (translated – with license – ‘People are what they eat’) has frequently been the subject of misconstrual and controversy. During 2007–2008, however, the phrase seems to have taken on a remarkably new lease of life; not through its adoption by a new generation of materialist philosophers, but rather in its ability to provide a useful lens through which to interpret tectonic shifts in economic and political reality.

The past eighteen months have seen a number of noteworthy events, developments and overt threats which have served to remind us forcefully of the extremely fragile nature of our existence and the genuine difficulties of ensuring sustainable economic growth. In the UK, for example, we have witnessed the accidental release of foot and mouth pathogens from the research facility at Pirbright, the rising threat of bluetongue disease to UK flocks and the spectacle of a celebrity chef taking the case for enhanced poultry welfare directly to the shareholders of a multi-billion pound retailer. Internationally, we have witnessed the deliberations of the High-Level Conference on World Food Security in Rome in June 2008 – grappling fitfully with rising commodity prices, the potential role of GM crops and the desirability of biofuels – and, more recently, the collapse in Geneva of the Doha Round of world trade talks after seven years of detailed and painful negotiation.

Against such a febrile background, few can remain oblivious to the interlocking and tightening relationships which are rapidly developing between food production, energy security, climate change and our general sense of economic and social well being. Many of the chapters in this volume bear varied witness to this particular confluence of concerns and provide as a result timely insights into the burgeoning agenda of contemporary ethical debate. And the questions are numerous and pressing. How can we survive as a species? And, what is perhaps more important, survive with dignity? How can humankind, as the dominant species on our planet, make imaginative use of ‘the good Earth’ while at the same time vouching sincerely to act as its true protector and guarantor? Is food simply a matter of utility or is it ultimately symbolic of something greater, regardless of one’s ethnicity, culture or religious persuasion? Can recourse to law, not least internationally, ensure that the interests of the most vulnerable are, at least from time to time, heard rather than ignored?

Part I of the volume attempts to explore some of the ethical issues that are raised by modern farming practices, contemporary food production and its associated regulation, agricultural subsidy regimes and animal welfare advocacy. Part II focuses on a number of bioethical issues, especially those associated with healthcare, reproduction, biobanking and the potential benefits of genetic research. Part III widens the scope to examine several contemporary hot debates in society, especially those associated with human competition and conflict. Finally Part IV consists of commentaries on a miscellany of issues that have found particular prominence in recent headlines. Despite the diversity of topics covered, several common themes emerge, including the rediscovery and redefinition of personal responsibility as we slowly face up to the constraints and limitations of the modern state or the relative impotence of international bodies to initiate or broker change for the betterment or enrichment of society.

Ethics as a distinct area of philosophical inquiry may of course be approached and understood in a number of ways. However, there is always a sense in which it arises both initially and practically from our hunger or thirst, in short our desire, to do what is right; this requires us not only to interrogate our motives routinely but also to scan the horizon widely and diligently for the likely outcomes of our actions. How does a self-perpetuating ‘me generation’ understand intergenerational justice and work towards its effective realization? How does a celebrity-obsessed culture learn to turn off the camera, microphone, mobile and laptop and begin to dig and plant, if not for victory, then new forms of self-reliance and self-worth? Can the past be the new future? Unfortunately the idyllic charms of Arcadia or its suburban equivalents are not easily reconcilable with the brash boastings of new technologies which promise a ‘brighter’ future through the endless exploitation or ‘makeover’ of the environment.

Ethical reflection in a rapidly changing world is rarely neat or tidy. None of our contributors are likely to imagine that what they offer here is more than a timely ‘report from the frontline’, the opportunity to tease out and articulate some broader principles, in short to provide us with useful food for thought. We are enormously grateful for their effort and enthusiasm.

![]() PART I

PART I

ETHICAL ISSUES IN AGRICULTURE AND FOOD![]()

Chapter 2

Modern Farming Practices and Animal Welfare

Joyce D’Silva

The last 50 years has seen a transformation of farming practices in the developed world and this transformation is now expanding rapidly to countries with fast-growing economies and populations like China and Brazil. Essentially, farming has changed from being a source of livelihood for individual families to being big business, from being family farm centred to being market and profit driven.

This scenario has created winners and losers. The winners are the big national or global agribusiness companies, many of which operate integrated operations, supplying breeding stock, feed and markets. Some would say consumers are winners too, as they can now eat far more meat, dairy products and eggs, as the relative price of these products has fallen.

The losers are often the traditional family farmers and the peasant farmers in developing countries, who now cannot compete with large-scale farming and who feel forced to give up and find alternative employment, often drifting to urban areas in desperation.

There are many arguments to say that the environment is also a loser. Mass production of farm animals results in pollution of water and soil and has a detrimental impact on water use, global feed crop production and deforestation. As we now know, livestock production is responsible for 18% of the greenhouse gases associated with human activity (Steinfeld 2006).

Consumers could be long-term losers too. Meat and dairy are responsible for much of the unhealthy saturated fat in ‘modern’ diets. In 2007 the World Cancer Research Fund recommended that people should eat ‘mostly plant foods’, cut down on red meat and avoid processed meat, in order to reduce the risk of certain cancers (World Cancer Research Fund /American Institute for Cancer Research 2007). So the cheap price of animal products may – inadvertently – be detrimental to our health.

Farm animals themselves may be the biggest losers from the growth in industrial production. Of course it would be inappropriate to ignore the advances in veterinary treatments available and our capacity to prevent disease outbreaks through routine vaccination. But these real improvements in prevention and treatment of disease may well be the only welfare benefits to farm animals over the last half century.

In fact, maximizing productivity has been the driving force in the increasingly intensive nature of the farming of animals and has resulted in serious threats to the health and welfare of the animals.

Selective Breeding

Farm animals have been selectively bred for centuries, but new technology has speeded up the rate of change enormously. Farm animals are normally selected for fast growth and high yield. Increased growth rates and muscular development or higher yields of milk or eggs can put enormous strain on both the skeleton and the cardiovascular systems of animals. A prime example of this is the modern meat chicken or broiler.

Broiler (meat) chickens

Most of the breeding stock for the 48 billion broiler chickens slaughtered globally per annum comes from just three companies. Many breeds are developed to reach market weight one day earlier each year (Cruikshank 2003). Already broiler chickens can grow from fluffy yellow chick to slaughter weight in less than six weeks.

In October 2007 one of these breed companies, Cobb-Vantress, issued a press release about their latest broiler, the Cobb 700, which, they say ‘is aimed at the rapidly expanding demand for breast meat for premium value-added products. The market is looking for broilers that will grow to heavier weights and achieve a high meat yield, with also the preferred breast muscle profile for the most valuable “whole muscle” products’ (Cobb-Vantress 2007).

This emphasis on breast muscle growth can be particularly damaging. Along with rapid growth rates, it can affect locomotion: the rapidly increasing body weight will place greater demands on the immature skeleton, and the change in shape can alter the forces produced during walking (Corr 2003). This places extra strain on the legs.

The impact of fast growth can be seen most clearly in the prevalence of lameness in the broiler chicken flock. In 2006 Defra published the results of a three year study into broiler lameness conducted by the University of Bristol. Five major UK broiler companies took part, and approximately 51,000 birds were gait scored, where an objective assessment was made of their walking ability. At least 27.6% of the chickens showed gait scores of 3 and above (out of a scale of one to five), revealing widespread lameness problems in the broiler chicken flock (University of Bristol 2006).

Even though broiler chickens get sent to slaughter at such a young age, around 1–2% may develop heart problems and ascites (fluid build-up in the chest) before this time. Genetic factors are one of the causes of the increased strain placed on the cardiovascular system due to fast growth (Julian 2000; Maxwell 1995).

In 2000, the European Commission’s Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare (SCAHAW) produced a report on the welfare of broilers saying ‘It is clear that the major welfare problems in broilers are those which can be regarded as side effects of the intense selection mainly for growth and feed conversion. These include leg disorders, ascites, sudden death syndrome in growing birds and welfare problems in breeding birds such as severe food restriction’ (SCAHAW 2000, Ch. 13).

They concluded: ‘Most of the welfare issues that relate specifically to commercial broiler production are a direct consequence of genetic selection for faster and more efficient production of chicken meat’ (SCAHAW 2000, Ch. 12).

This is a story with an ironic twist in its tail. Because broiler chickens are bred for this exponential growth rate, there is a problem in keeping the breeding birds alive and healthy long enough to reach puberty (at around 18 weeks) so that they can breed. If these birds ate as much as their descendants, many would develop high rates of lameness and heart disease by that time. To ensure they do live long enough, they are fed just enough food to keep them growing – sometimes this can be only 25% of what they might normally eat (Savory et al. 1993). When Compassion in World Farming challenged the UK government on this practice in the High Court in 2003, the judge agreed that such birds were in a state of ‘chronic hunger’ – while dismissing the case (R (Compassion in World Farming Limited) v Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs).

Turkeys

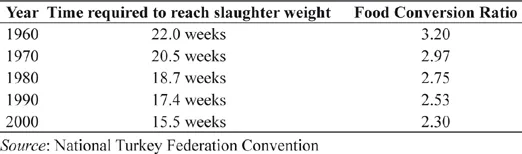

The modern farmed turkey bears little resemblance to its still-existing wild ancestor, who can live in tough conditions and fly (and is still widely hunted in North America). According to Dr James Bentley of British United Turkeys, a male turkey now grows to 19.6 kg at 21 weeks. He adds, ‘Current rates of genetic progress in live-weight are estimated at 3% per annum in male lines and 1% in female lines, giving an overall rate of progress in cross progeny of 2%’ (McKay et al. 2000). The ‘progress’ in breeding turkeys for rapid growth rates is shown in Table 2.1.

Leg and hip problems are common, and may be exacerbated by the practice of hanging these very heavy birds upside down from shackles at the slaughterhouse before they are stunned and killed.

In another twist to the poultry story, the breeding turkeys now grow so large that natural mating is impossible. People are employed to ‘milk’ the breeding turkey cockerels for their semen and all breeding is done by artificial insemination. Apparently some kinds of bestiality are quite legal!

Table 2.1 The effects of genetic selection on the performance of turkeys over time (males of a commercial breed)

‘Modern’ breeds of dairy cows

The effects of selective breeding can also be seen in the modern dairy herd. The average dairy cow in the UK now produces over 6800 litres of milk a year (Defra 2007), about 30% more than her counterpart of just 10 years ago (Defra 2004). This is five times more milk than her calf needs. Yield in the US is over 9000 litres a year (FAO 2007), indicating an even higher intensification. The breeding of larger and longer Holstein cows has meant that many dairy ‘cubicle’ sheds are now inadequate as, when the cows stand in their cubicles, their hind feet have to rest on the slurry-covered floor behind the cubicle rather than in the cubicle itself. Rates of 20% to 50% lameness per annum are regularly revealed in Western dairy herds (Webster 2005). A study in the Netherlands found that more than 83% of cows examined suffered lameness (Broom 2007). If not treated swiftly and well, the pain from lameness can be ‘severe and enduring’ (Webster 1987).

The actual shape of the cow has also been altered to give an ever-larger udder so that they can produce more milk. This is also one of the contributory factors to increasingly high levels of mastitis, painful udder inflammation. At any given time half of all US dairy cattle have mastitis (Adcock 1995). A wide-ranging investigation into the incidence of mastitis in dairy herds found 71 cases of mastitis per 100 cows per year in England and Wales. The authors estimated 47–65 cases of mastitis per 100 cows per year as the likely average (Bradley et al. 2007).

This extreme breeding has had adverse impacts on the calves born to such cows. Nearly all calves born to dairy cows are removed from their mothers within two days and the cows are milked to capacity for the dairy trade. Sadly, the bull calves are not favoured by the beef trade, being long and bony like their mothers, so many are killed shortly after birth and others are reared for a few months for veal. With most European veal farming centred in the Netherlands, Belgium and France, calves are exported to these countries in large numbers from eastern Europe and from the UK, subjecting them to long and stressful journeys.

Beef cattle

The ‘Belgian Blue’ breed of cattle is one extreme example of selective breeding for excessive muscle development (British breeders now refer to the ‘British Blue’). Breeders latched on to a ‘natural’ mutation in a gene which produced ‘double-muscled’ animals. Now these mighty creatures with their enormous hindquarters are highly prized for the large quantity of meat yielded by each animal. The downside is that the females don’t have a sufficiently expanding pelvic region to be able to give birth to their calves, and many births are by caesarean section (SCAHAW 2001).

Pigs

Modern breeds of pigs in the West are usually based on the genetics of two breeds, the Landrace and Large White. They have been selectively bred for high reproductive performance, often doubling the litter size of their ancestors. This can put a strain on the sow which has to produce enough milk and it can lead to more, weaker piglets, with a poorer survival rate. As with the chickens, faster growth rates can strain the metabolism and put pressure on heart and lungs. Leaner carcasses and paler skin make outdoor rearing, with all its welfare benefits, harder to achieve with such breeds, as they can be more susceptible to cold and heat stress and sunburn. Their longer bodies can put increased stress on their back legs (Arey and Brooke 2006, Ch. 10).

Confinement and Overcrowding

All animals on factory farms are confined in some way, either in individual pens, sometimes chained or tied by the neck, or confined to a small area of floor space in crowded pens, houses or cages. Natural behaviour and social groupings – as well as normal exercise – are thwarted in such conditions.

Veal calves

One of the most notorious examples of individual confinement is the keeping of calves in individual crates from the age of one week to slaughter at 4–6 months for veal production. For most o...