Chapter 1

Introduction: The Australian Census, Religious Diversity and the Religious ‘Nones’ among Indigenous Australians

James L. Cox and Adam Possamai

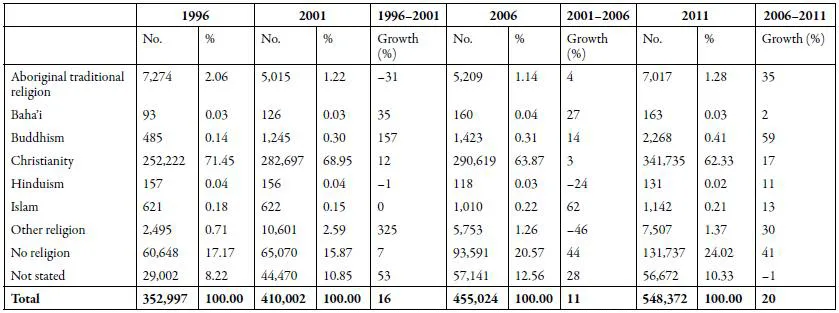

The motivation for this book originated from data reported in the 2011 Australian National Census, in which the number of Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders who claimed to have no religion or who did not state a religion was more than 130,000, approximately 24 per cent of the total Indigenous population. Between the prior census, in 2006, and the 2011 Census, there was a close to 41 per cent increase in the number of Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders in the ‘No Religion’ category, whereas for the whole Australian population the increase was notably less (29.41 per cent). Close to 99 per cent of Indigenous people who declared that they had ‘no religion’ did not provide any further specification. The remaining 1 per cent reported a variety of affiliations, including agnostic, atheist, humanist and rationalist (Onnudottir et al. 2013: 95).

This chapter analyses the meaning of these statistics in the light of a large body of literature that suggests that Aboriginal Australians have been mixing or blending their traditions with Christianity for well over a century, and, more recently, with Islam. The increase in the number of people identifying with the ‘No Religion’ category adds a further dimension to the study of the dynamic responses of Aboriginal people to powerful outside forces, including secularisation, urbanisation and technological advances. These and numerous other contemporary events focus our attention on the question which many chapters in this book address: Is the Indigenous population, like the wider Australian society, becoming increasingly secularised and irreligious, or can other factors be identified that explain the high percentage of Aboriginal people stating they have ‘no religion’? In order to provide an overarching theory according to which we can analyse these questions, we introduce, later in this chapter, the concept of ‘cultural hybridity’. Finally, we outline the structure of the book by briefly summarising how the contributors to this volume, coming from various academic fields with a variety of methodological and disciplinary approaches, offer diverse perspectives on the complex issues associated with Indigenous culture and its expressions in contemporary Australia.

Australian Census Data at a Glance

From 1996 to 2006, the number of Indigenous people claiming to be part of an Aboriginal Traditional Religion decreased from 7,274 to 5,209. The 2011 Census showed a reversal of this trend, with an increase of 35 per cent from the 2006 Census. The total is now 7,017 people, which is still less than shown in the 1996 Census, and represents a small percentage of the Indigenous population (1.28 per cent). We estimate this to be an under-representation, as Aboriginal Australians who are following both the traditional ways and Christianity (see below) may perhaps assume that Christianity, as a Western religion, is the correct answer to give in the census, a Western tool of measurement. We test this hypothesis in Chapter 9, where we analyse field studies undertaken among Australian Aboriginal groups in both urban and rural settings.

Reported adherence to Islam showed a significant increase (62 per cent) among Indigenous respondents in 2006, increasing from 622 people in 2001 to 1,010 in 2006. This growth continued, but at a much lesser rate (13 per cent), to reach a total number of 1,142 Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders who claimed Islam as their religion in the 2011 Census. The numbers of Indigenous people claiming to follow the Baha’i faith (n= 163) and Hinduism (n=131) are very small, even if the former group has seen constant growth. Buddhism had a strong peak in 2001 (157 per cent growth) and its Indigenous following has since continued to grow steadily (2,268 people in 2011). Of the major religions, Buddhism had the greatest increase in the number of adherents (57 per cent) for 2011.

The number of Indigenous people indicating they were Christian increased from 252,222 in 1996 to 290,619 in 2006, and further to 341,735 by 2011. Although this represents an increase in real numbers, in terms of the percentage of Indigenous people claiming allegiance to some form of Christianity, it actually reflects a decrease. Whereas, in 1996, 71.45 per cent of the Indigenous population asserted that they were from a Christian background, the percentage had fallen to 62.33 per cent in 2011. This decline in percentage is explained by the fact that there has also been a growth in absolute numbers of people who identify themselves as Indigenous, from 3 52,997 in 1996 to 548,373 in 2011. A comparison of the data for the Indigenous population for 2006 and 2011 with data for the entire Australian population for the same years reveals that the percentages of people claiming to be Christians are almost the same (Indigenous population: 64 per cent in 2006, 62 per cent in 2011; total Australian population: 64 per cent in 2006, 61 per cent in 2011).

Census data are the best available source of information for understanding religious trends among Aboriginal Australians at a national scale but are, unfortunately, not perfect, as they do not capture multiple approaches – such as a person’s being Christian and being involved in Aboriginal Traditional Religion at the same time (see below) – as the census question only asks and allows for a single answer. Further, there are significant issues to consider when using such data. As Schmidt (2014) points out, the census does not capture the daily customs of people and their vernacular religions. There are also problems of validity and reliability to take into account (Voas 2014). However, this type of data on religion is certainly invaluable when one is exploring general trends within a society (Wallis 2014) and is the best national instrument at our disposal.

An important conclusion we can draw from the results of the 2011 Census is that its findings undermine the colonial construct of what defines an ‘authentic’ Indigenous person. The statistics lead us to conclude that the contemporary everyday life of Aboriginal Australians is not restricted to their traditional spirituality and Christianity. Various groups of Australians, especially those with a New Age inclination, see Indigenous people as deeply spiritual (Muir 2007, 2013). While this may be true for some within the Indigenous population, the actual results of the census reveal this assumption to be based on ideas that tend to romanticise the customary beliefs, practices and way of life of Aboriginal peoples. Overall, according to census data, Indigenous Australians are more likely to identify as religious ‘nones’ than are non-Indigenous Australians.

Literature on the Mixture of Religions and Worldviews

One negative aspect of data derived from the census arises from the fact that the questions asked do not allow people to claim to follow more than one religion. As a result, the information provided does not unfortunately take into consideration the possibility that individuals may identify with two or more religions or that they may have fused elements of different religions to form a new religion, either as individuals or as part of a new religious movement. In Chapter 9, we use qualitative methods to analyse interviews that suggest that many Aboriginal Australians, both in urban and in rural contexts, mayclaim allegiance to aparticular

Table 1.1 Religious Affiliation of Indigenous Population in Australia, 1996–2011

religion at one moment while participating in another religion at another time, or may in other instances appear indifferent or even antagonistic to religion. This response is discussed in Part III of this book, in the contributions by Hart Cohen, Steve Bevis and Theresa Petray. In order to overcome the inflexibility of responses, as reflected in the census data, we have chosen to interpret the responses of our informants, which display the complexity of religious pluralism and changing religious allegiances, through the notion of cultural hybridity. In Chapter 9 we relate this concept to the actual interviews conducted and also to Cox’s definition of religion, as presented in Chapter 2, but in this present chapter it is necessary to explain what is meant by ‘cultural hybridity’ and to indicate why, as an analytical tool, we prefer this notion to its related concept, syncretism. Before presenting and examining the theory of cultural hybridity, we review some of the literature that refers to and exemplifies cultural mixing or blending of religious traditions with other traditions, or with the forces of modernity that have produced the ‘no religion’ response to the census question.

In the classic book on the ‘religious business’ of Aboriginal Australians, edited by Max Charlesworth, F. Brennan, a Roman Catholic priest, published a study on land rights and religion. Brennan (1998) only addresses Traditional Aboriginal Spirituality with regard to its connectedness with the land, and does not make reference to any possible synthesis with Christianity. As this author is a Christian priest, this might seem paradoxical. Schwarz and Dussart (2010: 8) discuss the bigger picture:

Aboriginal people involved in native title claims described themselves as committed to both Christianity and the Law. Trigger and Asche suggest that anthropologists have downplayed the presence of Christian belief and practice in preparing cases precisely because they feared that such acknowledgements would be antithetical to the interests of the claimants in the eyes of the court. Trigger and Asche call for a more sophisticated theory of change that can account for the complexity of Aboriginal people’s engagement with Christianity and their indigenous pasts.

Issues linking ‘authentic’ Aboriginal spiritualities to the land have been further complicated when ‘New Age’ spiritualities have been perceived to permeate traditional ones, as happened during the hearing of the Simpson Desert (Wangkangurru) Land Claim in Alice Springs in 1997 (Sutton 2009). Blending of New Age and Aboriginal spiritualities is not well reflected in the census data but is considered in the literature (for example, Hume 1996, Muir 2007, Possamai 2007, Sutton 2010).

Many cases examined in the literature refer to how Christianity and Indigenous religions have been seen as complementary rather than antagonistic. For example, Bill Edwards (2002) makes reference to Tjamiwa, a Pitjantjatjara preacher who employed Aboriginal knowledge to explain the Christian Bible. Reid (1983) describes some Aboriginal Australians adhering to Christian teachings while continuing to observe Yolngu religious law and ceremonies. Swain (1991) comments on the fact that Christian and traditional beliefs are often understood as working together rather than conflicting, to the point that some Aboriginal Australians in the desert regions follow ‘two laws’. Hume (1996) describes the Reverend Eddie Law, a Uniting Church minister and an Aboriginal Australian who seemed to see no inconsistency between Aboriginal traditional practices and Christian teaching. Victoria Grieves’s (2009) research focuses on Aboriginal spirituality and well-being in the light of what she describes as perceptions of ‘authentic’ Aboriginal spirituality, but she includes a brief reference linking it to Christianity. Sutton (2009: 71) provides a telling account of an exchange that illustrates one personal viewpoint concerning the relationship between Indigenous beliefs and the Christian teaching about life after death:

In the 1970s I once asked Silas Wolmby, a Wik man of Cape York Peninsula, what happened to people after death. He had been born in the bush between the wars at Kawkey, near Cape Keerweer, to semi-nomadic parents; he was multilingual, and had been initiated. He was also a mission-educated ex-stockman and had become, by then, a Presbyterian Reverend. He first gave me the standard Christian reply: if you’ve been good you go up to heaven; if you’ve been bad, you go down to hell. But, he added, he also believed ‘his’ way: your personal spirit-image (koethethmaayn) is sent by mourners to a localised spirit-centre in or close to your clan estate, and your inner spirit or soul (koetheth) goes west over the seas of the Gulf of Carpenteria to the place of the dead, Onchen. He had no trouble with this combination of Wik and Christian post-mortem cosmologies.

There is also a movement called the Rainbow Spirit Theology that integrates the traditions of Aboriginal culture with those of Christianity (Charlesworth et al. 2005). Cox (2014) studied this movement and claims that this theology has elevated traditional Aboriginal stories to the same level as the Old Testament. In ‘traditional’ Christianity, the stories of the Old Testament are used as a valid source of inspiration for the New Testament. It has been argued that for this Indigenous form of Christianity in Australia the same validity applies to the traditional Aboriginal stories, which are interpreted as an Indigenous equivalent to the Old Testament. The traditional story of creation, according the Rainbow Spirit Elders, primarily focuses on what they call the Rainbow Spirit, but which Cox demonstrates actually refers to the rainbow-serpent, which the anthropologist A.R. Radcliffe-Brown (1926: 24) contended was a ubiquitous symbol throughout Australia. Cox maintains that the Rainbow Spirit Elders deftly employed an intentional strategy that radically transformed Jesus Christ into the incarnation of the rainbow-serpent.

This sort of blending of Indigenous symbols with foreign religions is occurring not only in the case of Christianity, but also between Aboriginal culture and Islam (Onnudottir et al. 2013). The following comment made by an informant to a journalist illustrates this point:

[L]ots of similarities … [I]n Aboriginal culture there is a creator god, and the way I express my spirituality is through Islam. I don’t see the two as mutually exclusive. For me I choose Aboriginality as my culture and Islam as my faith. (Eugenia Flynn, in Morris 2007)

Stephenson (2010) makes reference to an extreme case of the mixing of Christianity, Islam and Aboriginal culture, and, according to Charlesworth et al. (2005), as there is not just one Aboriginal religion but a multitude, Aboriginal Australians are likely to be comfortable relating not only to numerous Aboriginal religions, but also to a variety of ‘world religions’. They even appear to resist orthodox monotheism and hold pluralist and non-exclusive beliefs.

Clearly, the census data – which show that in 2011 only 1.28 per cent of the Australian Indigenous population claimed to follow Aboriginal Traditional Religion, while 62.33 per cent were adherents of Christianity – might be subject to misunderstanding, because of the general assumption, prevalent in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, that each person should follow only one religion: that, in short, there can be only one truth, not many. This attitude is clearly reflected in the way the census is designed in Australia; it does not allow for the reporting of late-modern practices such as mixing and matching of religions (Possamai 2009) or non-Western practices of living according to more than one religion at the same time (Clarke 2006). Nor does it allow for the possibility that Aboriginal people may blend cultural traditions with secularist ideas, with the consequence that they may answer ‘no religion’ to the census question without rejecting many of their ancient Indigenous beliefs.

Aboriginal Australians and ‘No Religion’

Indigenous societies are neither static nor lost in the past. They have responded to historical changes and the forces of colonialism and Westernisation and have been deeply affected in many areas by the activitie...