![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

The twentieth-century vision of urban transport contained five crucial elements. First, the vision itself was of unimpeded, individual, motorized mobility. Along with this promise of individual mobility, went speed. Vehicles should at all times be able to travel at speeds consistent both with their design capacities and a reasonable level of safety for the drivers and passengers. Second, however, the attempt to realize this promise for all who could drive provoked traffic congestion, which then became the dominant transport problem of the twentieth century. Time lost moving at less than the optimum speed was time, and therefore money, wasted: the cost of congestion. Third, the solution to traffic congestion was to build more and better roads to accommodate private vehicles moving at speed. The higher the speed of the vehicles, the greater the separation between them necessary for the safety of people in cars, and so the more road space was required. Fourth, as realization of the promise became a historical fact, a simple technology was developed to project the growth of ‘demand’ for individual motorized mobility, and predict the road space needed to meet it. The fifth and final element was the implicit assumption that the planetary environment would for ever provide the necessary resources to fuel the vision and absorb its wastes.

This vision is powerful because it taps the human urge for freedom. ‘Of all the specific liberties’, wrote the philosopher Hannah Arendt, ‘which may come into our minds when we hear the word “freedom”, freedom of movement is historically the oldest and also the most elementary. Being able to depart for where we will is the prototypical gesture of being free’ (Arendt, 1955: 9). The first half of the twentieth century was full of the ideology of human emancipation by the private car (see Davison, 2004: 112–116). The vision is strongly compatible with liberal capitalism: freedom of consumer choice, the free market and, above all, the free movement of labour. The transport vision grew within the shell of free market economics, which in turn emerged from the powers that shaped the eighteenth century philosophy of the Enlightenment. So perhaps it is fair to talk of the ‘traffic enlightenment’.

The twentieth-century vision has nowhere been achieved, not even in that urban icon of the twentieth century, Los Angeles. Indeed the Urban Mobility Report, 2010, of the Texas Transportation Institute which tracks congestion in American cities reports Los Angeles as the most congested of the 15 largest US conurbations with 515 million hours travel delay in 2009 (Texas Transportation Institute, 2010). But in England the transformation of the urban environment necessary for its achievement was considered in the ‘Buchanan Report’, Traffic in Towns. In a portion of central London (east of Euston Road and north of Tottenham Court Road),

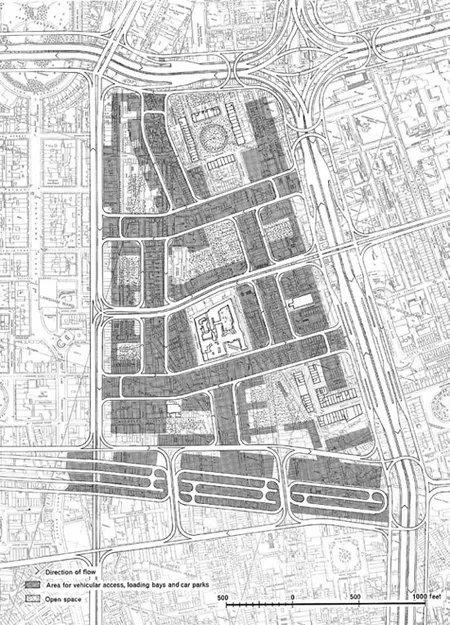

Figure 1.1 Buchanan’s design for partial redevelopment

Source: Traffic in Towns, A Study of the long term problems of traffic in urban areas, Report of the Working Group (led by Colin Buchanan) HMSO 1963 Figure 192, Page 147 ‘The design for partial redevelopment – plan at ground level showing the primary, district and local distributor road system together with the parking and service areas.’

the Buchanan team calculated the consequences ‘if every person should seek to go to work by car, every shopper to use a car, and the residents to have all they desired in the way of cars and parking spaces’ (Working Group, 1963: 130). Their conclusion: ‘when we considered the consequences for the primary [road] network of a vast continuous spread of areas similar to our study area, for this is what the middle of London really comprises, we realized that the network would become impossibly large and complicated’ (ibid.). Nevertheless the Buchanan team decided to try out a compromise version: not what might be needed within the area itself, but ‘what could be practically contrived in the way of a network to bring traffic to and from the area’ (ibid.). The radical transformation required for even this compromise is shown in Figure 1.1. It was a shocking wholesale demolition of the urban fabric, and its reconstruction around a pattern of motorways and ‘urban rooms’ segregated from the main flows of road traffic.

At this high point of the ‘traffic enlightenment’ in the 1960s, when popular belief in the virtue of the private car was strongest, the modernist architecture of reconstruction was still fashionable, the level of oil field discovery was peaking, and the ‘environment’ meant merely the local physical space, the Buchanan Report was a tipping point of sorts, or perhaps a Janus gateway between the past and the future, facing two ways, at once recognizing the impossible cost of the vision yet still hankering after its partial realization.

Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century in the developed world, there were many complaints and protests launched against implementation of the ‘traffic enlightenment’ vision of motorized individual mobility. But they gained little traction. Commenting on the Buchanan Report, Peter Self, then chairman of the Town and Country Planning Association, sensibly observed, ‘Should we not utilize the best means of transport for each particular purpose? For city centres, this would imply heavy use and almost complete reliance upon public transport, which is particularly well suited to this task. Conversely, the best prospects for motorization surely lie in the conception of a regional complex of new and expanded towns, each relatively small’ (Self, 1963: 1228). But by the 1960s an institutional carapace of organizations, policies, beliefs and practices had, throughout the developed world, been built around the vision, protecting it from challenge from without.

It was never enough to show that implementation of the vision had serious negative side effects or externalities. It was never enough to show that the vision was not equally applauded by everybody, that some sections of the population were losers from its pursuit. It was not enough to point out the vision’s large opportunity costs. It was not enough to demonstrate that pursuit of the vision in urban areas was destructive of the quality of the urban environment. It was not enough to show that building or improving roads only added to traffic on the road system. The policy path was sufficiently entrenched to brush off such challenges. Despite more subtle arguments to the contrary, the conventional wisdom continues to assert that fighting congestion is in the public interest, that the public are voting with their wallets to buy and use cars, and that the rest are vested interests with axes to grind. If the result is traffic congestion, the common sense solution is to build more road space to free up bottlenecks. It is politically ‘courageous’ to oppose such popular trends.

What has finally exposed the glorious vision as a lying mirage are two discoveries of the last century whose consequences have yet to be fully confronted by the state apparatuses of our times. These are the catastrophe of climate change induced by combustion of fossil fuel (Weart, 2003, provides a fine and readable account of the discovery of human induced climate change), and the peak and subsequent decline of the oil supply (Deffeyes, 2002; Campbell, 2005).1 Whatever the individual pleasures – and they are many – of the use of private motor vehicles, a vision in which their use is the dominant mode of urban transport cannot be defended when only a small rich minority will be able to afford it, and when its pursuit causes climate change. The world today stands on the threshold of a mobility catastrophe. The peak of oil production and climate change immediately confront the world, and governments around the world have yet to offer a robust and truly effective solution. It is not enough to argue that vehicles will have to change. Rather urban transport, and possibly our habits of mobility, will have to change. The forces preventing that change are now shown to be deeply irrational.

Many different kinds of values, some of them contradictory, are usually rolled up in the term ‘sustainable’ (Low, 2003). They will not be debated here. Suffice it to say that a transport vision that does not recognize and is not adapted to the realities of climate change and peak oil is not sustainable. The purpose of this book is to report an investigation of the institutional barriers preventing the development of a new vision compatible with these realities and in those terms ‘sustainable’.

Research Approach

This book draws on a major research project which set out to examine one particular policy domain, transport, in order to examine how discursive and institutional structures within government influence the achievement of sustainability targets. Our research questioned how far and fast government agencies move policy towards environmental sustainability. We argued that this depends not only on plans and programmes espousing the goal of sustainability, but also on the existence of barriers to implementation, and opportunities for innovation, resulting from existing discursive and institutional structures. The central hypothesis is that ‘discourse networks’ play a key role in the paradigm shift entailed by ‘sustainable development’.

The ‘discourse network’ is a concept used to explain the interconnectedness of ideas, decision-makers and their mental models of reality: what is ‘important’, what ‘the problem’ is, and how to go about solving it. For example, existing transport policy (with an emphasis on road building and private vehicle traffic) remains essentially unchanged so long as key actors support it. These actors do not have a unique idea of why it is necessary to support it but rather express a variety of ideas, or ‘storylines’ (following Hajer, 1995) that provide reasons for current policy solutions and may also suggest directions for change. : Hajer proposes that influence flows two ways: institutions manifest their existence through the intentional acts of their members but they also form and govern those intentions, partly by influencing the conceptions on which their members act (Hajer, 1995: 42–72). These conceptions are shaped by particular belief systems or ‘storylines’ (Davies and Harré, 1990). Storylines are metaphors, analogies, historical references and clichés, which hold discourse together, but they are also ‘prime vehicles of change’ (Hajer 1995: 63). He means that the development of new policy requires the incursion of new storylines.

As the research proceeded it became clear that what we were uncovering was a condition of institutional stasis, a failure to respond adaptively to the key challenges of the twenty-first century. To understand that condition we needed to set Hajer’s conceptual insights within the broader conceptual framework of institutional path dependence mapped out by theorists such as North (1990), Pierson (2000 a and b, 2004) and Torfing (2001).

Our empirical focus is the transport policy systems of three Australian cities: Melbourne, Sydney and Perth. We show how, over a period of 50–60 years, each has been extremely resistant to adoption of the paradigm of sustainability, except in rhetoric.

Our research design comprised four parts. First, using content analysis, we analysed the policy discourse of State and federal government policy documents in the period from the making of the first major land use and transport plans and policies in the late 1950s to around the year 2000. We conducted this for road infrastructure and for public transport in each city. In addition we analysed documents put out by key non-government actors (pressure groups): both pro-road groups and pro-public transport. Second, we turned to case studies of infrastructure projects in order to deepen the investigation. We focused on three major road building projects (one in each city). We examined the environmental impact statements and other planning reports, mapping arguments and investigating their logical coherence. Third, we analysed the institutions, looking at secular change in organization charts and the rules and procedures of agencies. Finally, we conducted a series of in-depth interviews with key informants, or policy shapers, in each city. These included those who had key influence over road infrastructure and public transport decisions. They included past and present Ministers of transport and land use planning, heads of State Government roads, public transport and planning agencies, persons responsible for case study projects and leading figures in pressure groups.

Structure of the Book

A ‘sustainable’ transport system means one that meets a variety of goals other than simple mobility. Some are rather intangible such as improved quality of urban space. Others, such as distributional equity in transport, are rarely measured, though increasingly important. In Chapter 2 we first briefly review the challenges of sustainable transport. We share the view put forward by Pacala and Socolow on the climate problem (2004: 968) that a ‘portfolio of technologies’ currently exists that can meet the world’s energy needs while stabilizing greenhouse emissions (‘reduced reliance on cars’ being one option). These authors specifically address the question of climate change, but we argue that the same holds for other major challenges of sustainability such as oil depletion and risk to health. We review the contents of a green transport portfolio and show that it is feasible. What then is blocking progress towards this end? As Banister (2005: 93) points out, ‘the role of institutions is crucial to the effective implementation of challenging options on sustainable development’; but time and again it appears that institutions block the way.

If politics in a democracy is an ongoing game, ‘institutions’ are the game’s rule book – the organizations set up to devise solutions and implement decisions, the norms, values, beliefs, assumptions and even language which imbue the process of decision-making. A key to understanding institutional behaviour, especially ‘policy lock-in’ (mentioned in the Stern Review p. 397) is the theory of ‘path dependence’. Chapter 3 explains in practical terms what this theory means for transport planning. The interpretation of path dependence explored in this chapter considers three related elements. The first is the path created for cities by the weight of physical infrastructure: the form an urban transport system takes over a period of time shapes the future of a city (Arthur, 1988; Woodlief, 1998). The second is the organizational power of the agencies making transport policy: policy is determined by agency power (Vigar, 2002; Dudley and Richardson, 2002). The third is the discourse that defines the transport problem for policy makers: policy is shaped and supported by arguments, perspectives and storylines (Low, 2005). The empirical focus of this book is the second and third elements: institutional path dependence.

The continuity of public policy from one political administration to the next is something most people take for granted and is accounted for to a considerable degree by path dependence. Root and branch change of policy with each change of government would be chaotic if it were not also impossible. So path dependence need not be seen as necessarily a policy failure. Rather, path dependence turns into policy failure when the path of policy development becomes inconsistent with the long term public interest. This failure is symptomatic of the insufficient capacity within a polity for long term policy review and redirection. The case study of this book is Australia. Current transport policy in Australia, like that in much of the developed world, is negatively path dependent and lacks the capacity for review and redirection.

Australian urban development over the last 50 years, characterized by low density peripheral growth loosely governed by planning laws, has had much in common with the development of the cities of North America and Europe. In the first part of Chapter 4 we briefly set the Australian scene in international context, drawing attention to the particularity of Australian urban geography and political constitution. In the second part we describe the trajectory of development of Australian transport planning with particular emphasis on the important role of the federal tier of government and how federal funding and policy shaped infrastructure at State level. Australia is a federal state and the funding for transport is shared between the federal (Commonwealth) and State governments. We draw attention to the key difference between public transport expenditure which is mostly operational, paid through State budgets, and road expenditure which is mostly capital expenditure, with a substantial portion provided by the federal government. In the final part of the chapter, critical periods (‘critical junctures’) are identified in the history of Australian cities and their governance that became turning points in urban transport planning.

City form – locational patterns of activity and buildings – is shaped by large scale infrastructure (Arthur, 1988) and this shaping can be termed ‘technical’ path dependence. For instance in Melbourne the sectoral pattern of development shaped by the railways continued to influence all journeys to work long after rail travel had been replaced by car travel as the dominant mode. However the physical reality of past investment in infrastructure should not be regarded as the only factor determining current transport policy. In the dispersed cities, characteristic of Australia and North America, altering (via planning policy) the urban form and population densities sufficiently to challenge over-reliance on the car is particularly challenging to implement and routinely opposed by community interests.2 Alternative strategies focused on integrated transport networks are available for dispersed areas (see HiTrans, 2005; Mees, 2000, 2009). Moreover, the substantial differences in policy in the three Australian cities of our case study, even though they share similar histories of road infrastructure investment, suggest the existence of other forms of path dependence shaping transport policy.

Chapters 5 and 6 explore the impact that the historical development of transport planning organizations has had on transport and infrastructure policy. In these chapters we examine the rule-bound social structures that enable collective action, the separate bureaucracies of roads and public transport. In Chapter 5 the development of the road planning agencies is analysed. The approach taken first describes the structural changes that occurred from the early days up to about the year 2000. In Sydney transport planning remains fragmented with roads and public transport agencies operating in separate compartments. In Melbourne the story is one of partial integration – varying at different periods. In Perth, by contrast, there has been a strong movement to integrate roads and public transport planning, and also transport with land use planning. We describe the reduction in the number of single purpose institutions (each with its own Minister) as the State governments have tried to integrate the planning of all transport together with land use planning. The examination of legislation, however, suggests that the road planning agency in all three cities retains considerable power, despite organizational change seeking to limit this power.

Following the framework of Chapter 5 the focus turns in Chapter 6 to the history ...