eBook - ePub

Medieval Philosophy

From 500 CE to 1500 CE

Britannica Educational Publishing, Brian Duignan

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Medieval Philosophy

From 500 CE to 1500 CE

Britannica Educational Publishing, Brian Duignan

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Philosophers of the Middle Ages endeavored to reconcile two seemingly incompatible concepts: religion and reason. By drawing extensively from the work of their predecessors, like Plato and Aristotle, medieval philosophers were able to find logical bases for their theological beliefs, thus using rationality to better comprehend their faith. This fascinating volume looks at the individuals who pioneered these new schools of thought and their lasting effects on our understanding of the nature of reality.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Medieval Philosophy an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Medieval Philosophy by Britannica Educational Publishing, Brian Duignan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophie & Philosophie des Mittelalters & der Renaissance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE ROOTS OF MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY

Medieval philosophy designates the philosophical speculation that occurred in western Europe during the Middle Ages—i.e., from the fall of the western Roman Empire in the late 5th century CE to the Renaissance of the 15th century. During the European Middle Ages philosophy was closely connected to Christian thought, particularly theology, and the chief philosophers of the period were churchmen.

The roots of medieval philosophy lie in the thought of philosophers and theologians who lived during the last three centuries of the ancient period, especially Plotinus (205–270 CE) and the early Church Fathers—notably Origen (c. 185–c. 254), Victorinus (died c. 304), Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335–c. 394), Ambrose (339–397), Nemesius of Emesa (flourished 4th century), Augustine of Hippo (354–430), Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (flourished c. 500), and Maximus the Confessor (c. 580–662). In the late 3rd and 4th centuries CE, Victorinus, Ambrose, and Augustine, among others, began to assimilate Neoplatonism—a mystical development of the thought of Plato (c. 428–c. 348 BCE)—into Christian doctrine in order to arrive at a rational interpretation of Christian faith. Thus, medieval philosophy was born of the confluence of Greek (and to a lesser extent of Roman) philosophy and Christianity. Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism, was already deeply religious, having come under the influence of Middle Eastern religions. Medieval philosophy continued to be characterized by this religious orientation. Its methods were at first those of Plotinus and, much later, those of Aristotle (384–322 BCE). But it developed within faith as a means of throwing light on the truths and mysteries of faith. Thus, religion and philosophy fruitfully cooperated in the Middle Ages. Philosophy, as the “handmaiden of theology,” made possible a rational understanding of faith. Faith, for its part, inspired Christian thinkers to develop new philosophical ideas, some of which became part of the philosophical heritage of the West.

Toward the end of the Middle Ages, this beneficial interplay of faith and reason started to break down. Philosophy began to be cultivated for its own sake, apart from—and even in contradiction to—Christian religion. This divorce of reason from faith, made definitive in the 17th century by Francis Bacon (1561–1626) in England and René Descartes (1596–1650) in France, marked the birth of modern philosophy.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The term Middle Ages refers to a period in European history that extended from the collapse of western Roman civilization in the 5th century CE to the Renaissance (variously interpreted as beginning in the 13th, 14th, or 15th century, depending on the region of Europe and on other factors). The term and its conventional meaning were introduced by Italian humanists engaged in a revival of classical learning and culture; their intent was self-serving, in that the notion of a thousand-year period of darkness and ignorance separating them from the ancient Greek and Roman world served to highlight the humanists’ own work and ideals. In a sense, the humanists invented the Middle Ages in order to distinguish themselves from it. The Middle Ages nonetheless provided the foundation for the transformations of the humanists’ own Renaissance.

This illustration shows Alaric before he invaded Rome. Bob Thomas/Popperfoto/Getty Images

The sack of the city of Rome by Alaric the Visigoth in 410 CE had enormous impact on the political structure and social climate of the Western world, for the Roman Empire had provided the basis of social cohesion for most of Europe. Although the Germanic tribes that forcibly migrated into southern and western Europe in the 5th century were ultimately converted to Christianity, they retained many of their customs and ways of life; the changes in forms of social organization they introduced rendered centralized government and cultural unity impossible. Many of the improvements in the quality of life introduced during the Roman Empire—such as a relatively efficient agriculture, extensive road networks, water-supply systems, and shipping routes—decayed substantially, as did artistic and scholarly endeavours. This decline persisted throughout the so-called Dark Ages (also called Late Antiquity, or the Early Middle Ages), from the fall of Rome to about the year 1000, with a brief hiatus during the flowering of the Carolingian court during the rule of Charlemagne (747–814). Apart from that interlude, no large kingdom or other political structure arose in Europe to provide stability. The only force capable of providing a basis for social unity was the Roman Catholic Church. The Middle Ages, therefore, present the confusing and often contradictory picture of a society attempting to structure itself politically on a spiritual basis. This attempt came to a definitive end with the rise of artistic, commercial, and other activities anchored firmly in the secular world in the period just preceding the Renaissance.

After the dissolution of the western Roman Empire, the idea arose of Europe as one large church-state, called Christendom. Christendom was thought to consist of two distinct groups of functionaries, the sacerdotium, or ecclesiastical hierarchy, and the imperium, or secular leaders. In theory, these two groups complemented each other, attending to people’s spiritual and temporal needs, respectively. Supreme authority was wielded by the pope in the first of these areas and by the emperor in the second. In practice the two institutions were constantly sparring, disagreeing, or openly warring with each other. The emperors often tried to regulate church activities by claiming the right to appoint church officials and to intervene in doctrinal matters. The church, in turn, not only owned cities and armies but often attempted to regulate affairs of state.

Europe and the Mediterranean Lands about 1190 – from the Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1926. Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

During the 12th century a cultural and economic revival took place; many historians trace the origins of the Renaissance to this time. The balance of economic power slowly began to shift from the region of the eastern Mediterranean to western Europe. The Gothic style developed in art and architecture. Towns began to flourish, travel and communication became faster, safer, and easier, and merchant classes began to develop. Agricultural developments were one reason for these developments; during the 12th century the cultivation of beans made a balanced diet available to all social classes for the first time in history. The population therefore rapidly expanded, a factor that eventually led to the breakup of the old feudal structures.

The 13th century was the apex of medieval civilization. The classic formulations of Gothic architecture and sculpture were achieved. Many different kinds of social units proliferated, including guilds, associations, civic councils, and monastic chapters, each eager to obtain some measure of autonomy. The crucial legal concept of representation developed, resulting in the political assembly whose members had plena potestas—full power—to make decisions binding upon the communities that had selected them. Intellectual life, dominated by the Roman Catholic Church, culminated in the 11th century in Scholasticism, a systematized and elaborately structured style of philosophy and philosophical instruction that dominated medieval universities until the early 15th century. Thomas Aquinas (c. 1224–74), the preeminent exponent of Scholasticism, achieved in his writings on Aristotle and the Church Fathers (the great Christian teachers and theologians of the 2nd to the 6th centuries CE) one of the greatest syntheses in Western intellectual history.

The breakup of feudal structures, the strengthening of city-states in Italy, and the emergence of national monarchies in Spain, France, and England, as well as such cultural developments as the rise of secular education, culminated in the birth of a self-consciously new age with a new spirit, one that looked all the way back to classical learning for its inspiration and that came to be known as the Renaissance.

ANCIENT PRECURSORS OF MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY

From the beginning of medieval philosophy, the natural aim of all philosophical endeavour to achieve the “whole of attainable truth” was clearly meant to include also the teachings of Christian faith. Although the idea of including faith had been expressed already by Augustine and the early Church Fathers, the principle was explicitly formulated by the pivotal, early 6th-century scholar Boethius (c. 470–524).

BOETHIUS

Born in Rome and educated in Athens, Boethius was one of the great mediators and translators, living in a narrow no-man’s-land that divided late ancient philosophy from early medieval philosophy. His famous book, De consolatione philosophiae (Consolation of Philosophy), was written while he, indicted for treachery and imprisoned by King Theodoric the Goth, awaited his own execution. It is true that the book is said to be, aside from the Bible, one of the most translated, most commented upon, and most printed books in world history; and that Boethius made (unfinished) plans to translate and to comment upon, as he said, “every book of Aristotle and all the dialogues of Plato.” But his reputation as one of the founders of medieval philosophy refers to quite another side of his work. Strictly speaking, it refers to the last sentence of a very short tractate on the Holy Trinity, which reads, “As far as you are able, join faith to reason.” Instead of “faith,” such concepts as revelation, authority, or tradition could be (and, indeed, have been) cited; and “reason,” though unambiguously meant to designate the natural powers of human cognition, could also be granted (and, in fact, has been granted) very different meanings. In any case, the connection between faith and reason postulated in this principle was from the beginning and by its very nature a highly explosive compound.

The consul Boethius holding sceptres in his left hand, ivory diptych, Byzantine, 5th–6th century; in the Museo Civico Cristiano, Brescia, Italy. SCALA/Art Resource, New York

Boethius himself already carried out his program in a rather extraordinary way: although his Opuscula sacra (“Sacred Works”) dealt almost exclusively with theological subjects, there was not a single biblical quotation in them: logic and analysis was all.

Boethius was destined to be for almost a millennium the last layperson in the field of European philosophy. His friend Cassiodorus (490–c. 585), author of the Institutiones, (an unoriginal catalog of definitions and subdivisions that nevertheless served as a sourcebook for the following centuries) occupied a position of high influence at the court of Theodoric (as did Boethius himself) and was also deeply concerned with the preservation of the intellectual heritage of the ancient world. Cassiodorus decided in his later years to quit his political career and to live with his enormous library in a monastery. This fact again is highly characteristic of the development of medieval philosophy: intellectual life needs not only teachers and students and not only a stock of knowledge to be handed down; there is also needed a certain guaranteed free area within human society, a kind of sheltered enclosure within which the concern for “nothing but truth” can exist and unfold. The Platonic Academy, as well as (for a limited time) the court of Theodoric, had been enclosures of this kind; but in the politically unsettled epoch to come “no plant would thrive except one that germinated and grew in the cloister.”

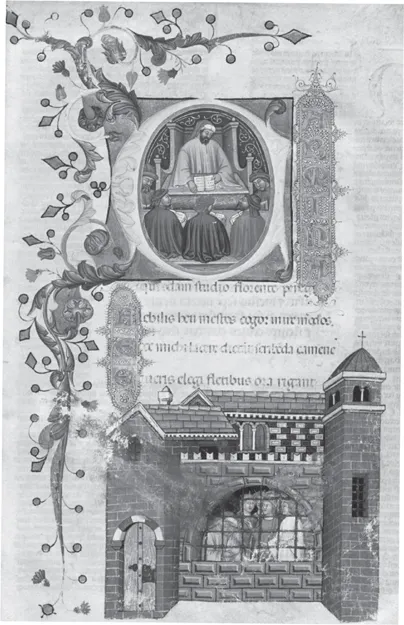

This illustration on vellum from “De Consolatione Philosophiae cum Commento,” shows Boethius in prison with students before his execution. Glasgow University Library, Scotland/The Bridgeman Art Library/Getty Images

PSEUDO-DIONYSIUS

The principle of the conjunction of faith and reason, which Boethius had proclaimed, and the way in which he himself carried it out were both based on a profound and explicit confidence in the natural intellectual capacity of human beings—a confidence that could possibly lead one day to the rationalistic conviction that there cannot be anything that exceeds the power of human reason to comprehend, not even the mysteries of divine revelation. To be sure, the great thinkers of medieval philosophy, in spite of their emphatic affirmation of faith and reason, consistently rejected any such rationalistic claim. But it must nonetheless be admitted that medieval philosophy on the whole, especially the systematic philosophies known as Scholasticism, contained within itself the danger of an overestimation of rationality, which recurrently emerged throughout its history.

On the other hand, there had been built in, from the beginning, a corrective and warning, which in fact kept the internal peril of rationalism within bounds—viz., the corrective exercised by the “negative theology” of the so-called Pseudo-Dionysius (flourished c. 500 CE), around whose writings revolved some of the strangest events in the history of Western culture. The true name of this protagonist is, in spite of intensive research, unknown. Probably it will remain forever an enigma why the author of several Greek writings (among them On the Divine Names, “On the Celestial Hierarchy,” and The Mystical Theology) called himself “Dionysius the Presbyter” and, to say the least, suggested that he was actually Dionysius the Areopagite, a disciple of Paul the Apostle. In reality, almost all historians agree that Pseudo-Dionysius, as he came to be called, was probably a Syrian Neoplatonist, a contemporary of Boethius. Whatever the truth of the matter may be, his writings exerted an inestimable influence for more than 1,000 years by virtue of the somewhat surreptitious, quasi-canonical authority of their author, whose books were venerated, as has been said, “almost like the Bible itself.” A 7th-century Greek theologian, Maximus the Confessor (c. 580–662), wrote the first commentaries on these writings; Maximus was followed over the centuries by a long succession of commentators, among them Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–80) and Aquinas. The main fact is that the unparalleled influence of Pseudo-Dionysius’s writings preserved in the Latin West an idea, which otherwise could have been repressed and lost (since it cannot easily be coordinated with rationality)—that of a “negative” theology or philosophy that could act as a counterbalance against an excessive emphasis on the powers of human reason. It could be called an Eastern idea present and effective in the Occident. But after the break between the Eastern and Western churches in the Great Schism (1054), which erected a wall between East and West that lasted for centuries, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, having become himself (through translations and commentaries) a Westerner “by adoption,” was the only one among all of the important Greco-Byzantine thinkers who penetrated into the schools of Western Christendom. Thus. ...