eBook - ePub

The History of Northern Africa

Britannica Educational Publishing, Amy McKenna

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The History of Northern Africa

Britannica Educational Publishing, Amy McKenna

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Alternately identified with either the countries of the Mediterranean, those of the Middle East, or other African territories, the nations of northern Africa occupy a unique physical and historical place. After centuries of fielding various foreign invaders, northern Africans have absorbed and co-opted Greek, Roman, and Arab peoples and traditions, among others. Under the pervasive turmoil that has ensued after colonial rule and internecine warfare, readers will encounter a region of various traditions that stands at a unique crossroads between several very different worlds.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The History of Northern Africa an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The History of Northern Africa by Britannica Educational Publishing, Amy McKenna in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'Afrique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire de l'AfriqueCHAPTER 1

EARLY HISTORY

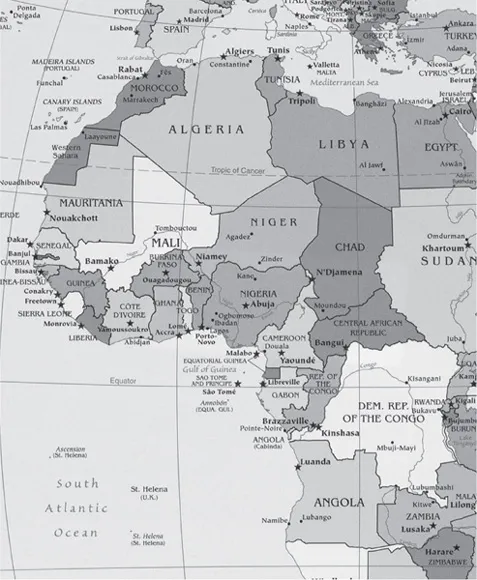

The northern region of the African continent is subject to various methods of definition. It has been regarded by some as stretching from the Atlantic shores near Morocco in the west to the Suez Canal and the Red Sea in the east. This region is commonly referred to as northern Africa and comprises the modern countries of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Sudan, as well as the territory of Western Sahara—all of which are included in this book.

The designation North Africa is also associated with this region of the continent. It refers to a smaller geographical area than that embraced by the term northern Africa—namely the countries of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, a region known by the French during colonial times as Afrique du Nord and by the Arabs as the Maghrib (“West”). The most commonly accepted definition of North Africa, and one that is also used in this book, includes the three above-mentioned countries as well as Libya. The regions here designated North Africa, however, have also been called Northwest Africa.

The ancient Greeks used the word Libya (derived from the name of a tribe on the Gulf of Sidra) to describe the land north of the Sahara, the territory whose native peoples were subjects of Carthage, and also as a name for the whole continent. The Romans applied the name Africa (of Phoenician origin) to their first province in the northern part of Tunisia, as well as to the entire area north of the Sahara and also to the entire continent. The Arabs used the derived term Ifrīqiyyah in a similar fashion, though it originally referred to a region encompassing modern Tunisia and eastern Algeria.

2008 map produced by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, highlighting the northern region of Africa. Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

In all likelihood, the Arabs also borrowed the word Barbar (Berber) from the Latin barbari to describe the non-Latin-speaking peoples of the region at the time of the Arab conquest, and it has been used in modern times to describe the non-Arabic-speaking population called Berbères by the French and known generally as the Berbers (although their term for themselves, Amazigh [plural: Imazighen], is now preferred). As a result, Europeans have often called North Africa the Barbary States or simply Barbary. (A frequent usage refers to the non-Phoenician and non-Roman inhabitants of classical times, and their language, as Berber. It should be stressed, however, that the theory of a continuity of language between ancient inhabitants and the modern Imazighen has not been proved; consequently, the word Libyan is used here to describe these people in ancient times.)

The countries of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia have also been known as the Atlas Lands, for the Atlas Mountains that dominate their northern landscapes, although each country, especially Algeria, incorporates sizable sections of the Sahara. Farther east in Libya, only the northwestern and northeastern parts of the country, called Tripolitania and Cyrenaica respectively, are outside the desert.

Although geographically proximate to the other countries of northern Africa, Egypt’s ancient civilization and long historical continuity—one marked by the ebb and flow of major religions, cultural trends, and foreign powers—is traditionally treated as a separate entity, one ultimately closer in distance and culture to the countries of the Middle East than to the countries to its west. Its role in this region of Africa, however, is undeniable. Sudan too is a place traditionally treated as atypical within its immediate geographic context, with its northern regions, today dominated by Islam and the Arabic language, closer to the Mediterranean world than its southern parts, where African languages and cultures hold the greatest sway. Sudan and Egypt are places where multifarious cultures have met, mixed, and clashed; they are the crossroads of the cultures and regions surrounding them. The histories of the two countries are also tightly bound. They may be in northern Africa, but they are not comfortably of that region. Their presence in this book, however, helps to underscore their often overlooked connections to the African countries nearby to them.

EARLY HUMANS AND STONE AGE SOCIETY

Although there is uncertainty about some factors, Aïn el-Hanech (in Algeria) is the site of one of the earliest traces of hominin occupation in the Maghrib. Somewhat later but better-attested are sites at Ternifine (near Tighenif, Alg.) and at Sidi Abd el-Rahmane, Mor. Hand axes associated with the hominin Homo erectus have been found at Ternifine, and Sidi Abd el-Rahmane has produced evidence of the same hominin dating to at least 200,000 years ago.

ARAB

Before the spread of Islam and, with it, the Arabic language, Arab referred to any of the largely nomadic Semitic inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula. In modern usage, it embraces any of the Arabic-speaking peoples living in the vast region from Mauritania, on the Atlantic coast of Africa, to southwestern Iran, including the entire Maghrib of North Africa, Egypt and Sudan, the Arabian Peninsula, and Syria and Iraq.

This diverse assortment of peoples defies physical stereotyping, because there is considerable regional variation. The early Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula were predominantly nomadic pastoralists who herded their sheep, goats, and camels through the harsh desert environment. Settled Arabs practiced date and cereal agriculture in the oases, which also served as trade centres for the caravans transporting the spices, ivory, and gold of southern Arabia and the Horn of Africa to the civilizations farther north. The distinction between the desert nomads, on the one hand, and town dwellers and agriculturists, on the other, still pervades much of the Arab world.

Islam, which developed in the west-central Arabian Peninsula in the early 7th century CE, was the religious force that united the desert subsistence nomads—the Bedouins—with the town dwellers of the oases. Within a century, Islam spread throughout most of the present-day Arabic-speaking world, and beyond, from Central Asia to the Iberian Peninsula. Arabic, the language of the Islamic sacred scripture (the Qur’an), was adopted throughout much of the Middle East and North Africa as a result of the rapidly established supremacy of Islam in those regions. Other elements of Arab culture, including the veneration of the desert nomad’s life, were integrated with many local traditions. Arabs of today, however, are not exclusively Muslim; some of the native speakers of Arabic worldwide are Christians, Druzes, Jews, or animists.

Traditional Arab values were modified in the 20th century by the pressures of urbanization, industrialization, detribalization, and Western influence. This is particularly evident with Arabs who live in cities and towns, where family and tribal ties tend to break down, and where women, as well as men, have greater educational and employment opportunity. It is not as evident with Arabs who continue to live in small, isolated farming villages, where traditional values and occupations prevail, including the subservience and home seclusion of women.

Succeeding these early hand ax remains are the Levalloisian and Mousterian industries similar to those found in the Levant. It is claimed that nowhere did the Middle Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) evolution of flake tool techniques reach a higher state of development than in North Africa. Its high point in variety, specialization, and standard of workmanship is named Aterian for the type site Bi’r al-‘Atir in Tunisia; assemblages of Aterian material occur throughout the Maghrib and the Sahara. Radiocarbon testing from Morocco indicates a date of about 30,000 years ago for early Aterian industry. Its diffusion over the region appears to have taken place during one of the periods of desiccation, and the carriers of the tradition were clearly adept desert hunters. The few associated human remains are Neanderthal, with substantial differences between those found in the west and those in Cyrenaica. In the latter area a date of about 45,000 years ago for the Levalloisian and Mousterian industries has been obtained (at Haua Fteah, Libya). The tools and a fragmentary human fossil of Neanderthal type are almost identical to those of Palestine.

The earliest blade industry of the Maghrib, associated as in Europe with the final supersession of Neanderthals by modern Homo sapiens, is named Ibero-Maurusian or Oranian (type site La Mouilla, near Oran in western Algeria). Of obscure origin, this industry seems to have spread along all the coastal areas of the Maghrib and Cyrenaica between about 15,000 and 10,000 BCE. Following the Ibero-Maurusian was the Capsian, the origin of which is also obscure. Its most characteristic sites are in the area of the great salt lakes of southern Tunisia, the type site being Jabal al-Maqta‘ (El-Mekta), near Gafsa (Capsa, or Qafṣah). The climate during both Ibero-Maurusian and Capsian times appears to have been relatively dry and the fauna one of open country, ideal for hunting. Between about 9000 and 5000 BCE upper Capsian industry spread northward to influence the Ibero-Maurusian and also eastward to the Gulf of Sidra. Since there is much evidence that the Neolithic culture of the Maghrib was introduced not by invasion but through the acceptance of new ideas and technologies by the Capsian peoples, it is probable that they were the ancestors of the Libyans known in historic times.

The spread of early Neolithic culture in Libya and the Maghrib occurred during the 6th and 5th millennia BCE and is characterized by the domestication of animals and the shift from hunting and gathering to self-supporting food production (often still including hunting). The pastoral economy, with cattle the chief animal, remained dominant in North Africa until the classical period. Although the new type of economy may have originated in Egypt or the Sudan, the character of the flint-working tradition of the Maghribian Neolithic argues in favour of the survival of much of the earlier culture, which has been called Neolithic-of-Capsian tradition. Accordingly, the technology of the transition, if not of independent local origin, is best explained by the gradual diffusion of new techniques rather than by the immigration of new peoples.

The Neolithic-of-Capsian tradition in the Maghrib persisted at least into the 1st millennium BCE with relatively little change and development; there was no great flourishing of late Neolithic culture and little that can be described as a Bronze Age. North Africa was wholly lacking in metallic ores other than iron, hence most tools and weapons continued to be made of stone until the introduction of ironworking techniques.

Prehistoric rock carvings have been found in the southern foothills of the Atlas Mountains south of Oran and in the Ahaggar and Tibesti ranges. While some are relatively recent, the great majority appear to be of the Neolithic-of-Capsian tradition. Some show animals now locally or even totally extinct, such as the giant buffalo, elephant, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus, in areas now covered by desert. While Egyptian-like patterns may be discerned, the character of the rock art is so different from that of Egypt that it can hardly be said to derive from it. On the other hand, it is very much later than the rock paintings of Paleolithic times in southwestern Europe, and an independent development is probable. The art is primarily that of a culture that continued to depend largely—though not exclusively—on hunting and that survived on the Saharan fringes until historical times.

There are many thousands of large, stone-built surface tombs in North Africa that appear to have no connection with earlier megalithic structures found in northern Europe, and it is unlikely that any of them is earlier than the 1st millennium BCE. Large structures in Algeria such as the tumulus at Mzora (177 feet [54 metres] in diameter) and the mausoleum known as the Medracen (131 feet [40 metres] in diameter) are probably from the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE and show Phoenician influence, though there is much that appears to be purely Libyan.

THE CARTHAGINIAN PERIOD

North Africa (with the exception of Cyrenaica) entered the mainstream of Mediterranean history with the arrival in the 1st millennium BCE of Phoenician traders, mainly from Tyre and Sidon in modern Lebanon. The Phoenicians were looking not for land to settle but for anchorages and staging points on the trade route from Phoenicia to Spain, a source of silver and tin. Points on an alternative route by way of Sicily, Sardinia, and the Balearic Islands also were occupied. The Phoenicians lacked the manpower and the need to found large colonies as the Greeks did, and few of their settlements grew to any size. The sites chosen were generally offshore islands or easily defensible promontories with sheltered beaches on which ships could be drawn up. Carthage (its name derived from the Phoenician Kart-Hadasht, “New City”), destined to be the largest Phoenician colony and in the end an imperial power, conformed to the pattern.

THE PHOENICIAN SETTLEMENTS

Tradition dates the foundation of Gades (modern Cádiz; the earliest known Phoenician trading post in Spain) to 1110 BCE, Utica (Utique) to 1101 BCE, and Carthage to 814 BCE. The dates appear legendary, and no Phoenician object earlier than the 8th century BCE has yet been found in the west. At Carthage some Greek objects have been found, datable to about 750 or slightly later, which comes within two generations of the traditional date. Little can be learned from the romantic legends about the arrival of the Phoenicians at Carthage transmitted by Greco-Roman sources. Though individual voyages doubtless took place earlier, the establishment of permanent posts is unlikely to have taken place before 800 BCE, antedating the parallel movement of Greeks to Sicily and southern Italy.

Material evidence of Phoenician occupation in the 8th century BCE comes from Utica and in the 7th or 6th century BCE from Hadrumetum (Sousse, Sūsah in Tunisia), Tipasa (east of Cherchell, Alg.), Siga (Rachgoun, Alg.), Lixus, and Mogador (Essaouira, Mor.), the last being the most distant Phoenician settlement so far known. Finds of similar age have been made at Motya (Mozia) in Sicily, Nora (Nurri), Sulcis, and Tharros (San Giovanni di Sinis) in Sardinia, and Cádiz and Almuñécar in Spain. Unlike the Greek settlements, however, those of the Phoenicians long depended politically on their homeland, and only a few were situated where the hinterland had the potential for development. The emergence of Carthage as an independent power, leading to the creation of an empire based on the secure possession of the North African coast, resulted less from the weakening of Tyre (the chief city of Phoenicia) by the Babylonians than from growing pressure from the Greeks in the western Mediterranean; in 580 BCE some Greek cities in Sicily attempted to drive the Phoenicians from Motya and Panormus (Palermo) in the west of the island. The Carthaginians feared that, if the Greeks won the whole of Sicily, they would move on to Sardinia and beyond, isolating the Phoenicians in North Africa. Their successful defense of Sicily was followed by attempts to strengthen limited footholds in Sardinia; a fortress at Monte Sirai is the oldest Phoenician military building in the west. The threat from the Greeks receded when Carthage, in alliance with Etruscan cities, checked the Phocaeans off Corsica about 540 BCE and succeeded in excluding the Greeks from contact with southern Spain.

CARTHAGINIAN SUPREMACY

By the 5th century BCE active military participation in the west by Tyre had doubtlessly ceased; from the latter half of the 6th century Tyre had been under Persian rule. Carthage thus became the leader of the western Phoenicians and in the 5th century formed an empire of its own, centred on North Africa, which included existing Phoenician settlements, new ones founded by Carthage itself, and a large part of modern Tunisia. Nothing is known of resistance from the indigenous North African populations, but it was probably limited because of the scattered nature of local societies and the lack of state formation. The actual stages of the growth of Carthaginian power are not known, but the process was largely completed by the beginning of the 4th century. The whole of the Sharīk (Cap Bon) Peninsula was occupied early, ensuring Carthage a fertile and secure hinterland. Subsequently it extended its control southwestward as far as a line running roughly from Sicca Veneria (El-Kef) to the coast at Thaenae (Thyna, or Thīnah; now in ruins). Penetration occurred south of this line later, Theveste (Tbessa, Tébessa) being occupied in the 3rd century BCE. In the Sharīk Peninsula, where the Carthaginians developed a prosperous agriculture, the native population may have been enslaved, while elsewhere they were obliged to pay tribute and furnish troops.

Carthage maintained an iron grip on the entire coast, from the Gulf of Sidra to the Atlantic coast of Morocco, establishing many new settlements to protect its monopoly of trade. These were mostly small, probably having only a few hundred inhabitants. The Greeks called them emporia, markets where native tribes brought articles to trade, which could also serve as anchorages and watering places. Permanent settlements in modern Libya were few and date to after the attempt by the Greek Dorieus to plant a colony there. Though in time fishing and agriculture played a part in their wealth, Leptis Magna with...