eBook - ePub

The Legislative Branch of the Federal Government

Purpose, Process, and People

Britannica Educational Publishing, Brian Duignan

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Legislative Branch of the Federal Government

Purpose, Process, and People

Britannica Educational Publishing, Brian Duignan

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Legislative Branch, created by Article I of the Constitution, is comprised of the House of Representatives and the Senate, which together form the United States Congress. This book not only studies the powers of the legislative branch and the organization of both houses of Congress, but also examines the legislative process and how a bill ultimately can become a law. This book gives readers a detailed look at how their government really works to both create and pass lasting legislation.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Legislative Branch of the Federal Government an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Legislative Branch of the Federal Government by Britannica Educational Publishing, Brian Duignan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Role of the Legislature

The characteristic function of all legislatures is the making of law. In most political systems, however, legislatures also have other tasks, such as selecting and criticizing the government, supervising administration, appropriating funds, ratifying treaties, impeaching officials of the executive and judicial branches of government, accepting or refusing executive nominations, determining election procedures, and conducting public hearings on petitions. Legislatures, then, are not simply lawmaking bodies. Neither do they monopolize the function of making law. In most systems the executive has a power of veto over legislation, and, even where this is lacking, the executive may exercise original or delegated powers of legislation. Judges, also, often share in the lawmaking process, through the interpretation and application of statutes or, as in the U.S. system, by means of judicial review of legislation. Similarly, administrative officials exercise quasi-legislative powers in making rules and deciding cases that come before administrative tribunals.

Legislatures differ strikingly in their size, the procedures they employ, the role of political parties in legislative action, and their vitality as representative bodies. In size, the British House of Commons is among the largest; the Icelandic lower house, the New Zealand House of Representatives, and the Senate of Nevada are among the smallest.

A legislature may be unicameral, with one chamber, or bicameral, with two chambers. Unicameral legislatures are typical in small countries with unitary systems of government—i.e., systems in which local or regional governments may exist but in which the central government retains ultimate sovereignty. Federal states, in which the central government shares sovereignty with local or regional governments, usually have bicameral legislatures, one house usually representing the main territorial sub-divisions. The United States is a classic example of a federal system with a bicameral legislation; the U.S. Congress consists of a House of Representatives, whose members are elected from single-member districts of approximately equal population, and a Senate, consisting of two persons from each state elected by the voters of that state. The fact that all states are represented equally in the Senate regardless of their size reflects the federal character of the American union. The federal character of the Swiss constitution is likewise reflected in the makeup of the country’s national legislature, which is bicameral.

A unitary system of government does not necessarily imply unicameralism. In fact, the legislatures of most countries with unitary systems are bicameral, though one chamber is usually more powerful than the other. The United Kingdom, for example, has a unitary system with a bicameral legislature, which consists of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. The Commons has become by far the more powerful of the two chambers, and the cabinet is politically responsible only to it. The Lords has no control over finances and only a modest suspensory veto with respect to other legislation (it may delay the implementation of legislation but not kill it). The parliaments of Italy, Japan, and France also are bicameral, though none of those countries has a federal form of government. Although in the United States all 50 states except Nebraska have bicameral legislatures, their governmental systems are unitary. In the 49 U.S. states with bicameral legislatures, the two houses have equal legislative authority, but the so-called upper houses—usually called senates—have the special function of confirming the governors’ appointments.

The procedures of the U.S. House of Representatives, which derive from a manual of procedure written by Thomas Jefferson, are among the most elaborate of parliamentary rules, requiring study and careful observation over a considerable period before members become proficient in their manipulation. Voting procedures worldwide range from the formal procession of the division or teller vote in the British House of Commons to the electric voting methods employed in the California legislature and in some other American states. Another point of difference among legislatures concerns their presiding officers. These are sometimes officials who stand above party and, like the speaker of the British House of Commons, exercise a neutral function as parliamentary umpires; sometimes they are the leaders of the majority party and, like the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, major political figures; and sometimes they are officials who, like the vice president of the United States in his role as presiding officer of the Senate, exercise a vote to break ties and otherwise perform mainly ceremonial functions.

Legislative parties are of various types and play a number of roles or functions. In the U.S. House of Representatives, for example, the party is responsible for assigning members to all standing committees; the party leadership fills the major parliamentary offices, and the party membership on committees reflects the proportion of seats held by the party in the House as a whole. The congressional party, however, is not disciplined to the degree found in British and some other European legislative parties, and there are relatively few “party line” votes in which all the members of one party vote against all the members of the other party. In the House of Commons, party-line voting is general; indeed, it is very unusual to find members voting against their party leadership, and, when they do, they must reckon with the possibility of penalties such as the loss of their official status as party members.

THE LEGISLATURE OF THE UNITED STATES

The U.S. Congress, the legislative branch of the American federal system, was established under the Constitution of 1789 and is separated structurally from the executive and judicial branches of government. As noted previously, it consists of two houses: the Senate, in which each state, regardless of its size, is represented by two senators, and the House of Representatives, to which members are elected on the basis of population. Among the express powers of Congress as defined in the Constitution are the power to lay and collect taxes, borrow money on the credit of the United States, regulate commerce, coin money, declare war, raise and support armies, and make all laws necessary for the execution of its powers.

The United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., is the meeting place of the U.S. Congress. © Corbis

THE CONTINENTAL AND CONFEDERATION CONGRESSES

The Congress established in 1789 was the successor of the Continental Congress, which met in 1774 and 1775–81, and of the Confederation Congress, which met under the Articles of Confederation (1781–89), the first constitution of the United States. The First Continental Congress was convened in Philadelphia in 1774 in response to the British Parliament’s passage of the Intolerable (Coercive) Acts, which were intended as punishment for the Boston Tea Party and other acts of colonial defiance. Fifty-six deputies in a single chamber represented all the colonies except Georgia. Peyton Randolph of Virginia was unanimously elected president, thus establishing usage of that term as well as “Congress.” Other delegates included Patrick Henry, George Washington, John and Samuel Adams, and John Jay. Meeting in secret session, the body adopted a declaration of personal rights, including life, liberty, property, assembly, and trial by jury, and denounced taxation without representation and the maintenance of the British army in the colonies without their consent.

Before the Second Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia in 1775, hostilities had already broken out between Americans and British troops at Lexington and Concord, Mass. New members of the Second Congress included Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. John Hancock and John Jay were among those who served as president. The Congress “adopted” the New England military forces that had converged upon Boston and appointed Washington commander in chief of the American army. It also acted as the provisional government of the 13 colony-states, issuing and borrowing money, establishing a postal service, and creating a navy. On July 2, 1776, with New York abstaining, the Congress “unanimously” resolved that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states.” Two days later, it solemnly approved this Declaration of Independence. The Congress also prepared the Articles of Confederation, which, after being sanctioned by all the states, became the first U.S. constitution in March 1781.

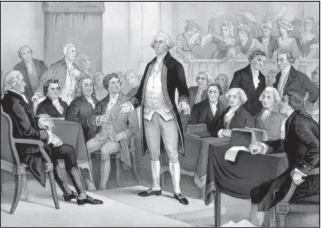

George Washington (centre) surrounded by members of the Continental Congress. Lithograph by Currier & Ives, c. 1876. Currier & Ives Collection, Library of Congress, Neg. No. LC-USZC2-3154

The Articles placed Congress on a constitutional basis, legalizing the powers it had exercised since 1775. This Confederation Congress continued to function until the new Congress, elected under the present Constitution, met in 1789.

THE CONGRESS OF 1789

The Constitutional Convention (1787) was called by the Confederation Congress for the purpose of remedying certain defects in the Articles of Confederation. But the Virginia Plan, presented by the delegates from Virginia and often dubbed the large-state plan, went beyond revision and boldly proposed to introduce a new, national government in place of the existing confederation. The convention thus immediately faced the question of whether the United States was to be a country in the modern sense or would continue as a weak federation of autonomous and equal states represented in a single chamber, which was the principle embodied in the competing New Jersey Plan, presented by several small states (and hence has been referred to as the small-state plan). This decision was effectively made when a compromise plan for a bicameral legislature—one chamber with representation based on population and one with equal representation for all states—was approved in mid-June.

The Constitution, as it emerged after a summer of debate, embodied a much stronger principle of separation of powers than was generally to be found in the state constitutions. The chief executive was to be a single figure (a composite executive was discussed and rejected) and was to be elected by an electoral college, meeting in the states. This followed much debate over the Virginia Plan’s preference for legislative election of the executive. The principal control on the chief executive, or president, against violation of the Constitution was the threat of impeachment (a criminal proceeding instituted by a legislative body against a public official). The Virginia Plan’s proposal that representation be proportional to population in both houses was severely modified by the retention of equal representation for each state in the Senate. But the question of whether to count slaves in the population was abrasive. After some contention, antislavery forces gave way to a compromise by which three-fifths of the slaves would be counted as population for purposes of representation and direct taxation (for representation purposes “Indians not taxed” were excluded). Slave states would thus be perpetually overrepresented in national politics; provision was also added for a law permitting the recapture of fugitive slaves (though in deference to republican scruples the word “slaves” was not used).

Contemporary political theory expected the legislature to be the most powerful branch of government. Thus, to balance the system, the executive was given a veto, and a judicial system with powers of review was established. It was also implicit in the structure that the new federal judiciary would have power to veto any state laws that conflicted either with the Constitution or with federal statutes. States were forbidden to pass laws impairing obligations of contract—a measure aimed at encouraging capital—and the Congress could pass no ex post facto law (typically, a law that retroactively makes criminal an act that was not criminal when performed). But the Congress was endowed with the basic powers of a modern—and sovereign—government. The prospect of eventual enlargement of federal power appeared in the clause, giving the Congress powers to pass legislation “necessary and proper” for implementing the general purposes of the Constitution.

By June 1788 the Constitution had been ratified by nine states, as required by Article VII. After elections held late that year, the first Congress under the new Constitution convened in New York on March 4, 1789.

POWERS AND FUNCTIONS OF THE MODERN CONGRESS

Although the two chambers of Congress are separate, for the most part, they have an equal role in the enactment of legislation, and there are several aspects of the business of Congress that the Senate and the House of Representatives share and that require common action. Congress must assemble at least once a year and must agree on the date for convening and adjourning. The date for convening was set in the Constitution as the first Monday in December. However, in the Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution, the date was changed to January 3. The date for adjournment is voted on by the House and the Senate.

Congress must also convene in a joint session to count the electoral votes for the president and vice president. Although not required by the Constitution, joint sessions are also held when the president or some visiting dignitary addresses both houses.

Of common interest to both houses of Congress are also such matters as government printing, general accounting, and the congressional budget. Congress has established individual agencies to serve these specific interests. Other agencies, which are held directly responsible to Congress, include the Copyright Royalty Tribunal, the Botanic Garden, and the Library of Congress.

The term of Congress extends from each odd-numbered year to the next odd-numbered year. For its annual sessions, Congress developed the committee system to facilitate its consideration of the various items of business that arise. Each house of Congress has a number of standing (permanent) committees and select (special and temporary) committees. Together the two chambers of Congress form joint committees to consider subjects of common interest. Moreover, because no act of Congress is valid unless both houses approve an identical document, conference committees are formed to adjust disputed versions of legislation.

At the beginning of a session, the president delivers a State of the Union address, which describes in broad terms the legislative program that the president would like Congress to consider. Later, the president submits an annual budget message and the report on the economy prepared by the president’s Council of Economic Advisors. Inasmuch as congressional committees require a period of time for preparing legislation before it is presented for general consideration, the legislative output of Congress may be rather small in the early weeks of a session. Legislation not enacted at the end of a session retains its status in the following session of the same two-year Congress.

In terms of legislation, the president may be considered a functioning part of the congressional process. The president is expected to keep Congress informed of the need for new legislation, and government departments and agencies are required to send Congress periodic reports of their activities. The president also submits certain types of treaties and nominations for the approval of the Senate. One of the most important legislative functions of the president, however...