eBook - ePub

World War II

People, Politics, and Power

Britannica Educational Publishing, William Hosch

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World War II

People, Politics, and Power

Britannica Educational Publishing, William Hosch

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

World War II was a very different war than had previously been fought in the course of history—new technologies and ideas were employed making way for widespread death and new atrocities. This book is a valuable resource that follows the war from the rise of Hitler to the dropping of the atomic bombs, through blitzkrieg and bombings, to the treaty that finally ended it all, noting the effects upon future world politics.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is World War II an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access World War II by Britannica Educational Publishing, William Hosch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE ORIGINS OF WORLD WAR II, 1929–39

The 1930s were a decade of unmitigated crisis culminating in the outbreak of a second total war. The treaties and settlements of the first postwar era collapsed with shocking suddenness under the impact of the Great Depression and the aggressive revisionism of Japan, Italy, and Germany. By 1933 hardly one of the economic structures raised in the 1920s still stood. By 1935 Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime had torn up the Treaty of Versailles and by 1936, the Locarno treaties as well. Armed conflict began in Manchuria in 1931 and spread to Abyssinia in 1935, Spain in 1936, China in 1937, Europe in 1939, and the United States and U.S.S.R. in 1941.

The context in which this collapse occurred was an “economic blizzard” that enervated the democracies and energized the dictatorial regimes. Western intellectuals and many common citizens lost faith in democracy and free-market economics, while widespread pacifism, isolationism, and the earnest desire to avoid the mistakes of 1914 left Western leaders without the will or the means to defend the order established in 1919.

The militant authoritarian states on the other hand—Italy, Japan, and (after 1933) Germany—seemed only to wax stronger and more dynamic. The Depression did not cause the rise of the Third Reich or the bellicose ideologies of the German, Italian, and Japanese governments (all of which pre-dated the 1930s), but it did create the conditions for the Nazi seizure of power and provide the opportunity and excuse for Fascist empire-building. Hitler and Benito Mussolini aspired to total control of their domestic societies, in part for the purpose of girding their nations for wars of conquest, which they saw, in turn, as necessary for revolutionary transformation at home. This ideological meshing of foreign and domestic policy rendered the Fascist leaders wholly enigmatic to the democratic statesmen of Britain and France, whose attempts to accommodate rather than resist the Fascist states only made inevitable the war they longed to avoid.

THE ECONOMIC BLIZZARD

The Smoot–Hawley Tariff, the highest in U.S. history, became law on June 17, 1930. Conceived and passed by the House of Representatives in 1929, it may well have contributed to the loss of confidence on Wall Street and signaled American unwillingness to play the role of leader in the world economy. Other countries retaliated with similarly protective tariffs, with the result that the total volume of world trade spiraled downward from a monthly average of $2,900,000,000 in 1929 to less than $1,000,000,000 by 1933. The credit squeeze, bank failures, deflation, and loss of exports forced production down and unemployment up in all industrial nations. In January 1930 the United States had 3,000,000 idle workers, and by 1932 there were more than 13,000,000. In Britain 22 percent of the adult male work force lacked jobs, while in Germany unemployment peaked in 1932 at 6,000,000. All told, some 30,000,000 people were out of work in the industrial countries in 1932.

Panicky retrenchment and disunity also rendered the Western powers incapable of responding to the first violation of the post–World War I territorial settlements. On Sept. 10, 1931, Viscount Cecil assured the League of Nations that “there has scarcely ever been a period in the world’s history when war seemed less likely than it does at the present.” Just eight days later officers of Japan’s Kwantung Army staged an explosion on the South Manchurian Railway to serve as pretext for military action. Since 1928, China had seemed to be achieving an elusive unity under Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists (KMT), now based in Nanjing. While the KMT’s consolidation of power seemed likely to keep Soviet and Japanese ambitions in check, resurgent Chinese nationalism also posed a threat to British and other foreign interests on the mainland. By the end of 1928, Chiang was demanding the return of leased territories and an end to extraterritoriality in the foreign concessions. On the other hand, the KMT was still split by factions, banditry continued widespread, the Communists were increasingly well-organized in remote Jiangxi, and in the spring of 1931 a rival government sprang up in Canton. To these problems were added economic depression and disastrous floods that took hundreds of thousands of lives.

Japan, meanwhile, suffered from the Depression because of its dependence on trade, its ill-timed return to the gold standard in 1930, and a Chinese boycott of Japanese goods. But social turmoil only increased the appeal of those who saw in foreign expansion a solution to Japan’s economic problems. This interweaving of foreign and domestic policy, propelled by a rabid nationalism, a powerful military-industrial complex, hatred of the prevailing distribution of world power, and the raising of a racist banner (in this case, antiwhite) to justify expansion, all bear comparison to European Fascism. It was when the parliamentary government in Tokyo divided as to how to confront this complex of crises that the Kwantung Army acted on its own, invading Manchuria. Mancuria, rich in raw materials, was a prospective sponge for Japanese emigration (250,000 Japanese already resided there) and the gateway to China proper. The Japanese public greeted the conquest with wild enthusiasm.

China appealed at once to the League of Nations, which called for Japanese withdrawal in a resolution of October 24. But neither the British nor U.S. Asiatic fleets (the latter comprising no battleships and just one cruiser) afforded their governments (obsessed in any case with domestic economic problems) the option of intervention. The tide of Japanese nationalism would have prevented Tokyo from bowing to Western pressure in any case. In December the League Council appointed an investigatory commission under Lord Lytton, while the United States contented itself with propounding the Stimson Doctrine, by which Washington merely refused to recognize changes born of aggression. Unperturbed, the Japanese prompted local collaborators to proclaim, on Feb. 18, 1932, an independent state of Manchukuo, in effect a Japanese protectorate. In March 1933, Japan announced its withdrawal from the League of Nations, which had been tested and found impotent, at least in East Asia.

The League also failed to advance the cause of disarmament in the first years of the Depression. The London Naval Conference of 1930 proposed an extension of the 1922 Washington ratios for naval tonnage, but this time France and Italy refused to accept the inferior status assigned to them. In land armaments, the policies of the powers were by now fixed and predictable. Fascist Italy, despite its financial distress, was unlikely to take disarmament seriously, while Germany, looking for foreign-policy triumphs to bolster the struggling Republic, demanded equal treatment. Either France must disarm, they said, or Germany must be allowed to expand its army. The League Council nonetheless summoned delegates from 60 nations to a grand Disarmament Conference at Geneva beginning in February 1932. When Germany failed to achieve satisfaction by the July adjournment it withdrew from the negotiations.

Negotiations were delayed by a sudden initiative from Mussolini in March. He called for a pact among Germany, Italy, France, and Britain to grant Germany equality, revise the peace treaties, and establish a four-power directorate to resolve international disputes. Mussolini appears to have wanted to downgrade the League in favour of a Concert of Europe, enhancing Italian prestige and perhaps gaining colonial concessions in return for reassuring the Western powers. The French watered down the plan until the Four-Power Pact signed in Rome on June 7 was a mass of anodyne generalities. Any prospect that the new Nazi regime might become part of collective security agreements disappeared on Oct. 14, 1933, when Hitler denounced the unfair treatment accorded Germany at Geneva and announced its withdrawal from the League of Nations.

THE TREATY OF VERSAILLES IS SHREDDED

THE RISE OF HITLER

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazis) exploited the resentment and fear stemming from Versailles and the Depression. Its platform was a clever, if contradictory, mixture of socialism, corporatism, and virulent assertion in foreign policy. The Nazis outdid the Communists in forming paramilitary street gangs to intimidate opponents and create an image of irresistible strength, but unlike the Communists, who implied that war veterans had been dupes of capitalist imperialism, the Nazis honoured the Great War as a time when the German Volk had been united as never before. The army had been “stabbed in the back” by defeatists, they claimed, and those who signed the Armistice and Versailles agreements had been criminals. What was worse, they claimed, was the continued conspiracy against the German people by international capitalists, Socialists, and Jews. Under Nazism alone, they insisted, could Germans again unify under “ein Reich, ein Volk, ein Führer” and get on with the task of combating Germany’s real enemies. This amalgam of fervent nationalism and rhetorical socialism, not to mention the charismatic spell of Hitler’s oratory and the hypnotic pomp of Nazi rallies, was psychologically more appealing than flaccid liberalism or divisive class struggle. In any case, the Communists (on orders from Moscow) turned to help the Nazis paralyze democratic procedure in Germany in the expectation of seizing power themselves.

Heinrich Brüning resigned as chancellor in May 1932, and the July elections returned 230 Nazi delegates. After two short-lived rightist cabinets foundered, German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor on Jan. 30, 1933. The president, parliamentary conservatives, and the army all apparently expected that the inexperienced, lower-class demagogue would submit to their guidance. Instead, Hitler secured dictatorial powers from the Reichstag and proceeded to establish, by marginally legal means, a totalitarian state. Within two years the regime had outlawed all other political parties and coopted or intimidated all institutions that competed with it for popular loyalty, including the German states, labour unions, press and radio, universities, bureaucracies, courts, and churches. Only the army and foreign office remained in the hands of traditional elites. But this fact, and Hitler’s own caution at the start, allowed Western observers fatally to misperceive Nazi foreign policy as simply a continuation of Weimar revisionism.

Adolf Hitler, leader of the Nazi Party, arrives at a rally in Nürnberg in September of 1933. Officers, including Rudolf Hess, follow closely behind. Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hitler’s worldview dictated a unity of foreign and domestic policies based on total control and militarization at home and war and conquest abroad. In Mein Kampf he ridiculed the Weimar politicians and their “bourgeois” dreams of restoring the Germany of 1914. Rather, the German Volk could never achieve their destiny without Lebensraum (“living space”) to support a vastly increased German population and form the basis for world power. Lebensraum, wrote Hitler in Mein Kampf, was to be found in the Ukraine and intermediate lands of eastern Europe. This “heartland” of the Eurasian continent (so named by the geopoliticians Sir Halford Mackinder and Karl Haushofer) was especially suited for conquest since it was occupied, in Hitler’s mind, by Slavic Untermenschen (subhumans) and ruled from the centre of the Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy in Moscow. By 1933 Hitler had apparently imagined a step-by-step plan for the realization of his goals. The first step was to rearm, thereby restoring complete freedom of maneuver to Germany. The next step was to achieve Lebensraum in alliance with Italy and with the sufferance of Britain. This greater Reich could then serve, in the distant third step, as a base for world dominion and the purification of a “master race.” In practice, Hitler proved willing to adapt to circumstances, seize opportunities, or follow the wanderings of intuition. Sooner or later politics must give way to war, but because Hitler did not articulate his ultimate fantasies to the German voters or establishment, his actions and rhetoric seemed to imply only restoration, if not of the Germany of 1914, then the Germany of 1918, after Brest-Litovsk. In fact, his program was potentially without limits.

To be sure, Mussolini was gratified by the triumph of the man he liked to consider his younger protégé, Hitler, but he also understood that Italy fared best while playing France and Germany against each other, and he feared German expansion into the Danubian basin. In September 1933 he made Italian support for Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss conditional on the latter’s establishment of an Italian-style Fascist regime. In June 1934 Mussolini and Hitler met for the first time, and in their confused conversation (there was no interpreter present) Mussolini understood the Führer to say that he had no desire for Anschluss. Yet, a month later, Austrian Nazis arranged a putsch in which Dollfuss was murdered. Mussolini responded with a threat of force (quite likely a bluff) on the Brenner Pass and thereby saved Austrian independence. Kurt von Schuschnigg, a pro-Italian Fascist, took over in Vienna. In Paris and London it seemed that Mussolini was one leader with the will and might to stand up to Hitler.

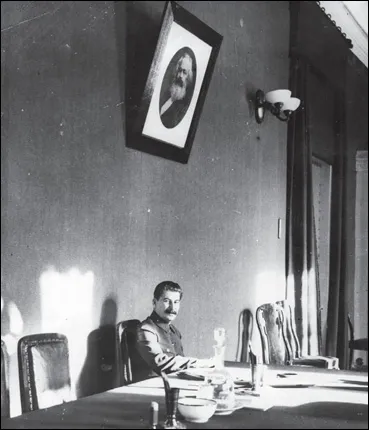

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin at work in his office. A portrait of German philosopher Karl Marx, whose theories are credited as the foundation for communism, hangs on the wall over Stalin’s head. James Abbe/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Joseph Stalin, meanwhile, had repented of the equanimity with which he had witnessed the Nazi seizure of power. Before 1933, Germany and the U.S.S.R. had collaborated, and Soviet trade had been a rare boon to the German economy in the last years of the Weimar Republic. Still, the behaviour of German Communists contributed to the collapse of parliamentarism, and now Hitler had shown that he, too, knew how to crush dissent and master a nation. The Communist line shifted in 1934–35 from condemnation of social democracy, collective security, and Western militarism to collaboration with other anti-Fascist forces in “Popular Fronts,” alliance systems, and rearmament. The United States and the U.S.S.R. established diplomatic relations for the first time in November 1933, and in September 1934 the Soviets joined the League of Nations, where Maksim Litvinov became a loud proponent of collective security against Fascist revisionism.

Thus, French foreign minister Louis Barthou’s plan for reviving the wartime alliance from World War I and arranging an “Eastern Locarno” began to seem plausible—even after Oct. 9, 1934, when Barthou and King Alexander of Yugoslavia were shot dead in Marseille by an agent of Croatian terrorists. The new French foreign minister, the rightist Pierre Laval, was especially friendly to Rome. The Laval–Mussolini agreements of Jan. 7, 1935, declared France’s disinterest in the fate of Abyssinia in implicit exchange for Italian support of Austria. Mussolini took this to mean that he had French support for his plan to conquer that independent African country. Just six days later the strength of German nationalism was resoundingly displayed in the Saar plebiscite. The small, coal-rich Saarland, detached from Germany for 15 years under the Treaty of Versailles, was populated by miners of Catholic or social democratic loyalty. They knew what fate awaited their churches and labour unions in the Third Reich, and yet 90 percent voted for union with Germany. Then, on March 16, Hitler used the extension of French military service to two years and the Franco-Soviet negotiations as pretexts for tearing up the disarmament clauses of Versailles, restoring the military draft, and beginning an open buildup of Germany’s land, air, and sea forces.

In the wake of this series of shocks Britain, France, and Italy joined on April 11, 1935, at a conference at Stresa to reaffirm their opposition to German expansion. Laval and Litvinov also initialed a five-year Franco-Soviet alliance on May 2, each pledging assistance in case of unprovoked aggression. Two weeks later a Czech-Soviet pact complemented it. Laval’s system, however, was flawed; mutual suspicion between Paris and Moscow, the failure to add a military convention, and the lack of Polish adherence meant that genuine Franco-Soviet military action was unlikely. The U.S.S.R. was in a state of trauma brought on by the Five-Year Plans; the slaughter and starvation of millions of farmers, especially in the Ukraine, in the name of collectivization; and the beginnings of Stalin’s mass purges of the government, army, and Communist Party. It was clear that Russian industrialization was bound to overthrow the balance of power in Eurasia, hence Stalin was fearful of the possibility of a preemptive attack before his own militarization was complete. But he was even more obsessed with the prospect of wholesale rebellion against his regime in case of invasion. Stalin’s primary goal, therefore, was to keep the capitalist powers divided and the U.S.S.R. at peace. Urging the liberal Western states to combine against the Fascists was one method. Exploring bilateral relations with Germany, as in the 1936 conversations between Hjalmar Schacht and Soviet trade representative David Kandelaki, was another.

Italy and Britain looked askance at the Franco-Soviet combination, while Hitler in any case sugar-coated the pill of German rearmament by making a pacific speech on May 21, 1935, in which he offered bilateral pacts to all Germany’s neighbours (except Lithuania) and assured the British that he, unlike the Kaiser, did not intend to challenge them on the seas. The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of June 18, which countenanced a new German navy though limiting it to not larger than 35 percent the size of the British, angered the French and drove a wedge between them and the British.

ITALIAN AGGRESSION

The Stresa Front collapsed as soon as Paris and London learned the price Mussolini meant to exact for it. By 1935 Mussolini had ruled for 13 years but had made little p...