eBook - ePub

Culture, Ideology and Politics (Routledge Revivals)

Essays for Eric Hobsbawm

Raphael Samuel, Gareth Stedman Jones, Raphael Samuel, Gareth Stedman Jones

This is a test

Share book

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Culture, Ideology and Politics (Routledge Revivals)

Essays for Eric Hobsbawm

Raphael Samuel, Gareth Stedman Jones, Raphael Samuel, Gareth Stedman Jones

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1982, this book is inspired the ideas generated by Eric Hobsbawm, and has taken shape around a unifying preoccupation with the symbolic order and its relationship to political and religious belief. It explores some of the oldest question in Marxist historiography, for example the relationship of 'base' and 'superstructure', art and social life, and also some of the newest and most problematic questions, such as the relationship of dreams and fantasy to political action, or of past and present — historical consciousness — to the making of ideology. The essays, which range widely over period and place, are intended to break new ground and take on difficult questions.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Culture, Ideology and Politics (Routledge Revivals) an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Culture, Ideology and Politics (Routledge Revivals) by Raphael Samuel, Gareth Stedman Jones, Raphael Samuel, Gareth Stedman Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia del mundo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Culture

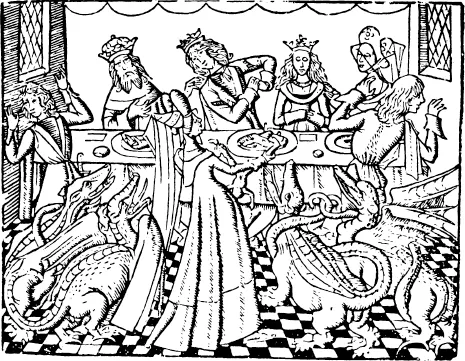

4 WOMEN AND THE FAITH IN ICONS IN EARLY CHRISTIANITY*

Judith Herrin**

The cult of icons presents several paradoxes. It runs directly counter to the Old Testament prohibition of ‘graven images’, which was binding on early Christian communities, and it represents an essentially pagan art form, the commemoration of the dead, ancestors, rulers, heroes and divinities both mortal and immortal. This prompts the question: how did icons come to hold such a central position in Christian art? Had the church simply ignored the heathen roots and Mosaic interdiction of this type of representative art? Or had it justified a Christian adaptation and re-employment of older art forms by theological argument? One answer was given in the eighth century, when the Byzantine empire tried to resolve the apparent contradiction built into this early Christian art by destroying icons and figurative art. A different one was developed by the western church, which was not prepared to do away with its own tradition, supported by no less an authority than Pope Gregory the Great: ‘For what writing [scriptura] presents to readers, this a picture [pictura] presents to the unlearned who behold, since in it even the ignorant see what they ought to follow: in it the illiterate read. Hence, and chiefly to the nations [gentibus], a picture is instead of reading.’1 The challenge of iconoclasm revealed a deep commitment to Christian art, both in the East where icon veneration finally triumphed and in the West where destruction was rejected outright. When under attack the icons found intense support throughout the church, although this iconophile response differed in important respects. In this paper I shall be primarily concerned with the eastern response, that faith in icons which represents a more personal type of dedication to Christian images.

Posing this problem means, in effect, seeking the origins of Christian art, a topic far too large and complex for a short paper. But within this long development the role of the icon is significant and merits special consideration. Icons centre attention on one of the basic problems of the early church, the representation of holy persons, while simultaneously revealing features of the non-Christian antecedents of this art. I am concerned with this tradition. My approach will not be that of an art historian, nor will I deal with the theological debates over the propriety of figurai imagery. I will discuss the place of icons in worship, their character and the way they came to symbolize the holy and mediate between earth and heaven. In particular, as icons became a vivid focus of devotion, they began to embody human relations with God the Creator and Ruler of the entire Christian world. And I will argue that women played a notable part in this developing cult of icons.

So without denying the theological dilemma of Christian representational art, I want to concentrate on some features of Late Antique Mediterranean culture, shared by Jews and Gentiles, pagan and Christian alike. These provided a common social experience within which the artistic evolution of the Christian church took place. In particular, the first part of this chapter will be devoted to a discussion of funerary art, for this represents one of the most striking ways whereby Christians transmitted pagan rituals and artistic forms to their new faith. In the second part, I will examine some of the reasons for the preservation of these forms, once assimilated to a Christian mode, when they came under attack in the East, and will ask how much that response informs us about the role of women in the cult of icons.

I

It is characteristic of human societies to treat death, the possibility of life after death and obligations to dead ancestors as a major concern. The finality of material existence in this world is regularly contrasted with more eternal values and the completely immaterial hereafter. Burial rituals and funerary monuments everywhere reveal a basic concern shared by societies as different as nomadic Siberia and Pharaonic Egypt. While some leave more direct evidence in the form of written accounts of mourning or in particularly impressive tomb architecture, none totally discount the needs of the dead in whatever other world they have passed on to.

In the pre-Christian Mediterranean world a variety of beliefs was attached to the fate of the deceased, but the maintenance of family shrines and the perpetuation of the memory of ancestors through prescribed ceremonies was widely observed. The early Christian communities cannot have been unaware of their contemporaries’ customs in this respect: from the Gospel of St John (ch. 19, 40) they would have known that Christ’s body was embalmed with spices and bound with strips of linen in the Jewish fashion. In addition, the existence of classical mausolea and tombs must have been as familiar as the Egyptian habit of mummifying (which had been adopted by the first-century AD Jews of Palestine) and the Greek preference for cremation. The commemoration of dead rulers in funerary monuments and living emperors through images to which respect had to be shown, extended this practice into the daily political sphere. Tomb stones, funerary urns, sarcophagi and burial portraits provided proof of the ubiquitous concern to record and cherish the dead. The chief differences lay in the manner by which this was to be effected. Preservation of the body was naturally abhorrent to those who believed that the soul was released by death, but even they marked the final resting place of the ashes. Others, who did not practise incineration, built tombs which sometimes became public shrines. In the case of emperors, in particular, the distinction between private and public burial was almost impossible to maintain, and these tombs were rarely restricted to immediate kin.2

As the first few generations of Christians were almost all converts from other faiths, they must have brought direct knowledge of traditional burial methods with them into the church. These were strengthened by subsequent missionary activity, for even in the fifth and sixth centuries non-believers of many varieties were still adopting the faith. The influence of such customary practices and means of commemorating the dead should not be underestimated. Christian burial customs, using both cemeteries and catacombs, marking graves with a portrait of the deceased and celebrating the good fortune of ancestors with annual feasting at the tomb, followed normal, heathen practice. Only by their belief in the resurrection and the life to come did the Christians set themselves apart from their contemporaries.3 And this distinguishing feature of the faith did not preclude funerary representations considered traditional in all cults. So it is hardly surprising that Christian art is found precisely in those places reserved for graves, often next door to examples of pagan and Jewish art on the graves of non-Christians. It is possible that the private houses where these early Christian communities met to celebrate their faith were also decorated, but if so this type of art has not survived. Only one building adapted for the specific function of baptism is known from the first three centuries AD - the baptistery at Dura Europos, an eastern frontier town destroyed by a Persian army in 256 and fortunately preserved under sand in the North Syrian desert. Interestingly, this small monument is completely overshadowed by other cult buildings in the same town: the spectacular frescoes of the synagogue, large statues of Palmyrene gods in their temple and the decorated Mithraeum.4 Even if the paucity of other evidence has attributed undue prominence to the tomb art of the early church, great significance was attached to the burial rite, not only in Christianity but in most other Late Antique religions. Viewed in this perspective, catacomb art proves extremely revealing not only of Christian attitudes towards visual representation, but also of the long pre-history of burial ceremony which deeply influenced the early church.

Another aspect of funerary art which made it suitable for the early communities was that it avoided some of the most obvious, official, pagan forms of art, works displayed in public places throughout the Roman world. Greek excellence in the field of free-standing statuary and the survival of many ancient statues of gods, athletes, rulers and philosophers, often naked, may have prevented Christians from using this medium. A fourth-century emperor, on the other hand, could re-use a statue of Apollo as his own. Imperial statues and portraits in every city of the empire reminded the early Christians of the temporal rulers of the world, often persecutors, who demanded a secular worship. Recognizing this public cult celebrated in life-like paintings and life-size monuments, they shunned material images, reinforcing Christ’s command to worship their heavenly Lord in spirit and in truth. Although attempts are occasionally made to argue that the early church was not implacably hostile to human representation, attention has more often been given to the apparent reluctance to portray the Founder of the faith and the preference for symbolic decoration. Evidently there was some anxiety associated with Christian figurai art which could easily be mistaken for its pagan equivalent.5

The earliest surviving Christian graves are marked by shrines where offerings could be made, and by symbolic representations of the faith, doves of peace, loaves and fishes, the IXΘYC anagram and the chi-rho sign. In addition, Christian families sometimes displayed a portrait of the departed and an inscription recording the name and genealogy.6 For all the faithful, the duty of honouring the dead was such an important one that Christian graves were bound to attract the type of art normally set up at tombs. In this respect the Egyptian tradition of preserving the body in mummy form and the Roman practice of depicting the deceased in a most life-like fashion were very influential. The former required that the mummy should contain a portrait painted during the individual’s lifetime, usually in encaustic (wax) on wood; this was inserted into the mummy over the face (see plates 1 and 2, the complete mummy of Artemiodoros and the portrait of a young woman, pagan works of the second century AD). The latter custom identified the grave with a sculpted bust or a portrait in low relief, painting or gold glass. Both seem to have been employed by Christians with sufficient means. For the poor humbler imitations were used. There was no hesitancy about such funerary portraiture, it was the accepted manner of naming a grave and was widely adopted for private family tombs.7 In this way pre-Christian art forms were put to use in the church by those who converted from other faiths, and by those whose families had been Christian for generations. This art avoided the most obvious pagan associations of ancient statuary, but it was none the less rooted in ancient custom shared by many cults.

The tombs or places of martyrdom attached to the Christian heroes of Roman persecution naturally attracted particular attention and these gradually developed into cult sites. In their determination to honour and revere those who had suffered death for the faith, Christians of the third and fourth centuries created new centres and new forms of worship. The traditional places of death and burial of the martyrs, tombs already set apart both by their physical setting and by the character of the deceased, begin to serve a public function as martyria. Pilgrims visit these sites with a heightened sense of awe, recording in graffiti their belief that the figures enshrined would intercede for them, protecting and guiding their lesser co-religionaries.8 In the slow transition from plain grave to cult shrine a variety of means for indicating divine approval, ranging from the saint’s halo to the Hand of God receiving the martyr, were employed to emphasize the proximity of such heroes to God himself. Thus, by the early fourth century the cult of martyrs had established both the main type of Christian building and its artistic decoration (churches were still a rarity). These patterns were inherited by the first Christians who benefited from Constantine I’s decision to grant the church an official status, tolerated and equal to the many other cults of the empire.

This fundamental change in the position of the Christian communities was responsible, by and large, for the development of Christian art. Once the faith could be celebrated openly and above ground, it needed larger buildings and these required decoration. Constantine led the way in commissioning new monuments and a whole range of wealthy patrons followed his example. I should like to stress just one aspect of the growth of this official art: the importance of Constantine’s ‘discovery’...