eBook - ePub

New Firms and Regional Development in Europe

David Keeble, Egbert Wever, David Keeble, Egbert Wever

This is a test

Share book

- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Firms and Regional Development in Europe

David Keeble, Egbert Wever, David Keeble, Egbert Wever

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

When originally published in 1986, this book was one of the first to deal solely with the urban and regional incidence and development implications of new firm formation in particular EU countries. It reviews the extent of and reasons for geographical variation in numbers of new firms, examines the nature of such firms and assesses the regional impact and policy implications in various EC countries.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is New Firms and Regional Development in Europe an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access New Firms and Regional Development in Europe by David Keeble, Egbert Wever, David Keeble, Egbert Wever in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Pequeñas empresas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter one

INTRODUCTION

David Keeble

Egbert Wever

Egbert Wever

Introductory Remarks

Differences in the extent of unemployment between regions are regarded as a problem in most Western European countries. The regional policies which have resulted aim to bring the number of workers in a region more into line with the number of jobs available there. In most countries, this has involved a strategy of taking ‘work to the workers’. By applying particular policy measures, governments have attempted to create additional employment in those regions where the shortage of jobs is greatest. The object has generally been to make such regions more attractive as a location for ‘new’ firms and employment. Until recently this meant persuading existing companies to relocate their activities in a problem assisted area, or more commonly to establish a branch plant there. Initially preoccupied with manufacturing activities, regional policy has since the 1960s been extended to embrace certain service industries, so far with only limited success.

In all European countries, the policy of finding an external solution for regional employment problems has however in recent years become less and less successful. Deepening recession and a generally poor economic climate have greatly reduced opportunities for attracting branch plants. The number of relocations of existing plants to problem areas has also diminished. One reason for this is that the most important push-factor for long-distance industrial migration, a shortage of labour in the major origin areas, has disappeared. Another closely connected reason is the growth of high unemployment in the traditional origin areas, such as the big cities of northern Europe, themselves. Local authorities there are often now actively promoting the retention of local industry and employment, in contrast to the situation only a decade or so ago. The result of these changes is that no region, least of all the problem areas, can rely any longer solely on an external solution for solving their employment problems.

In consequence, regional policies are increasingly emphasising the need to harness the indigenous potential of the problem areas. One approach to this is by stimulating innovation (in a very broad sense) within the region’s existing plants. This reorientation is to a certain extent reflected in the growing attention economic geographers are now giving to the relations between innovation, technology and regional development. The other approach to increasing the indigenous economic potential of a region is to stimulate local entrepreneurship. The growing interest in the phenomenon of new firm formation within the framework of regional policy provides much of the context for this book. However, the interest shown by economic geographers and regional economists in new firm formation is not only prompted by the role new firms play in regional policy. Perhaps even more important is the broadly-accepted argument that large corporations will not be able, at least in the foreseeable future, to provide enough jobs for the working populations of our European countries. Since David Birch published his research on ‘the job generation process’ in 1979, many other commentators have also suggested that newly-created small firms can make an important contribution to the creation of new jobs. Even when such expectations are pitched too high, which they often are, this possibility explains the interest in new firm formation shown by politicians, development agencies, journalists and scientists.

New Firm Formation: A Framework

This book focusses on new firms and research by economic geographers and regional economists on their spatial distribution in the countries of the European Community. Essentially, however, we can distinguish two different sorts of new firms. Both play an important role in regional policies. The first category consists of the relocated firm and the newly-established branch plant of a firm already operating elsewhere. For the destination region these are new firms, although the companies to which they belong did already exist elsewhere before. This category is the more traditional focus of regional policy. Much geographical and economic research has already been devoted to these firms and their importance for economic development and employment in destination regions. Some of the more characteristic research questions investigated by economic geographers include the following:

– does this category of new firms contribute to the diversification of the regional economy?

– what impacts do these firms exert on the destination region by the salaries paid to local workers, by the material and non-material linkages, etc.?

– are there negative effects on the destination region because of external control?

– what are the motives for relocation (push and pull factors) and what factors influence the locational choice of branch plants?

– what was the nature of the search procedure for the new location?

– did the relocated firm meet problems in its new location and was its choice on balance satisfactory?

The considerable volume of firm migration which occurred in Europe in the 1960s and early 1970s stimulated a great deal of research into the above questions, as for example that reported in Klaassen and Molle (1983). In view of our already-extensive knowledge of migrant new firms, this category will not be considered further here.

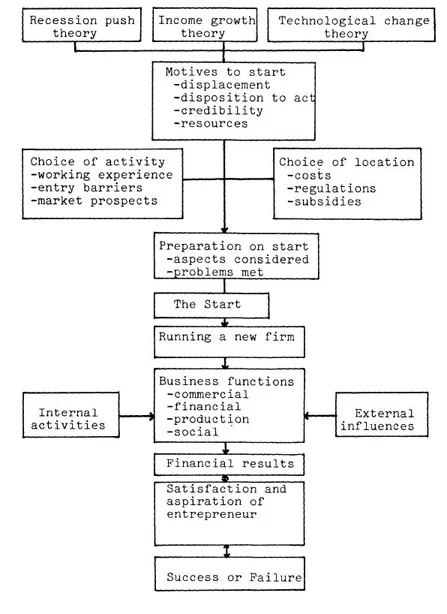

The central theme of this book concerns the second category of new firms, namely those which did not exist before and which are set up by their founders as independent businesses. Connected with this kind of new firms is the concept of the ‘entrepreneur’. In considering the importance of new independent firms of this type for urban and regional economic development, several aspects can be distinguished. Moreover, each of these aspects has a spatial dimension. Fig. 1 gives an overview of the discussion in the remainder of this section.

Perhaps the most obvious starting-point for considering new enterprise creation and the stimulation of entrepreneurship is the question, why does someone set up his own business, despite all the risks of such a venture? Some interesting ideas here can be derived from Shapero (1983). He distinguishes four main motives which can stimulate an individual to start a firm. The first of these is called the displacement factor. This usually explains the precise timing of business formation. Sometimes the firm founder has very little choice in this respect. Many refugees, for example, start their own firm because they have no other obvious way to survive. In the same way, longterm unemployment, or the threat of it, can stimulate people to start up in business for themselves. To Shapero such negative firm formation motives are very important: ‘threat works more than incentive’. Of course there are also more positive motives for starting a new firm. It may be that these positive motives are more important than negative stimuli in our West European welfare states. Examples of positive factors are the desire to be recognised as a craftsman, the wish to use one’s capacities to the full, the ambition to be one’s own boss, and the urge to become rich.

Fig. 1. The new firm formation process.

The second main motive Shapero calls the disposition to act. Many people feel the need, for one reason or another, to change something in their lives. However, not every refugee, long term unemployed person or frustrated employee, feeling that need decides to start a firm. Those who do take that step want freedom and independence more than anything else. Therefore a good reason for wanting to start will only lead to a new firm in reality if the entrepreneur has the appropriate personality.

The third main motive is called credibility. The decision to set up a new firm will be influenced not only by the personality of the potential entrepreneur, but also by the social position and esteem enjoyed by businessmen in a particular society. In some ‘social climates’ entrepreneurship will flourish more than in others. In a society where employment in the civil service confers high social status and economic security, the pull of entrepreneurship will be diminished. Shapero himself gives the following very illustrative example: ‘In Italy, I found that a man of education who started a small business lost social status. In the USA, that man is a folk-hero’. Political opinions and attitudes can also play a role. Someone who proclaims the class struggle and moves in like-minded circles is unlikely to participate in setting-up a new capitalist enterprise. The reverse is also true. Many new firm founders come from families, a member of which is already a businessman and which provide encouragement and social support. This is especially important in the context of a Western European society in which someone who fails in business loses status.

The last main motive identified by Shapero is the availability of resources. This can be regarded as the more material stimulus provided by a given local, regional or national environment. Such stimuli can perhaps help a potential new firm to cross the notorious threshold of successful new enterprise formation by reducing risks and costs either nationally or in particular regions (for example, by special financial and tax incentives, management and marketing counselling, or subsidised housing costs). From the policy perspective, this last motive is of particular interest because of the possibility of public intervention. However, in explaining regional variations in numbers of new firms, the availability of resources appears to be a much less significant influence than the ‘ social climate’ or credibility factor. In traditional new firm studies focussing on the urban incubator hypothesis, for example, perhaps too much attention has been paid to material and too little attention to social stimuli.

The decision to set up one’s own firm leads inevitably to a further series of questions. The first of these is ‘what type of firm will I start?’ In many cases the answer to this question is already given, in that the entrepreneur has only a limited choice. The most important factor here is the previous experience of the new firm founder. The overwhelming majority of founders inevitably set up businesses in activities in which they have working experience. This also means that in general new firms conform to the existing regional economic structure. In the short-run at least, their contribution to diversification may therefore be modest. On the other hand, this does not mean that similar numbers of new firms are founded in all industrial sectors. The most important reason for this seems to be the presence or absence of barriers to entry. For a potential entrepreneur who has been a blue-collar worker in a blast furnace setting up a new firm will be more difficult than for a similar worker experienced in the clothing industry. To some extent this may also explain why the influence of demand factors appears to be relatively limited. A number of stagnating or declining sectors are for example characterised by low entry barriers and therefore by many new firm start-ups. The fact that a potential entrepreneur believes that he will succeed where others have failed will also diminish the influence of market demand on new firm formation rates. As sectors dominated by small firms are at the same time usually characterised by low entry barriers, this may be one reason why many new firm founders have gained their previous work experience in small and medium-sized firms. It may of course also be true that work experience in small firms is more varied and provides better allround training for becoming an independent businessman. In a region which possesses many small firms the credibility factor may also be important, in that there are more examples of successful ‘role models’ and mentors whom potential founders can copy than in an area where the majority are employed in one or two large companies.

The next question which the potential entrepreneur has to answer is ‘where do I set up my firm?’ To an even greater extent than with firm type, the founder usually has little choice in this respect. Most entrepreneurs set up their new firms in the area in which they already live. The new independent firm is therefore a genuinely endogenous answer to regional unemployment problems. Of course this does not mean that new firms in a particular region are only established by residents who were born and bred in the area. Many recent new firms in rural areas of northern Europe appear in fact to have been set up by migrants coming from large cities, and who have moved to these rural areas because of t...