![]()

1

Iran-zamin

Iran-zamin, "the land of Iran," means more than a place of habitation and extends beyond the present political entity. For Iranians, Iran-zamin is that area where Iranian peoples have maintained their special way of life through centuries of invasion, social change, and political and religious trumoil. Iran-zamin is the birthplace and home of a unique Iranian culture—the product of an ancient relationship between diverse peoples and their homeland.

The Physical Environment

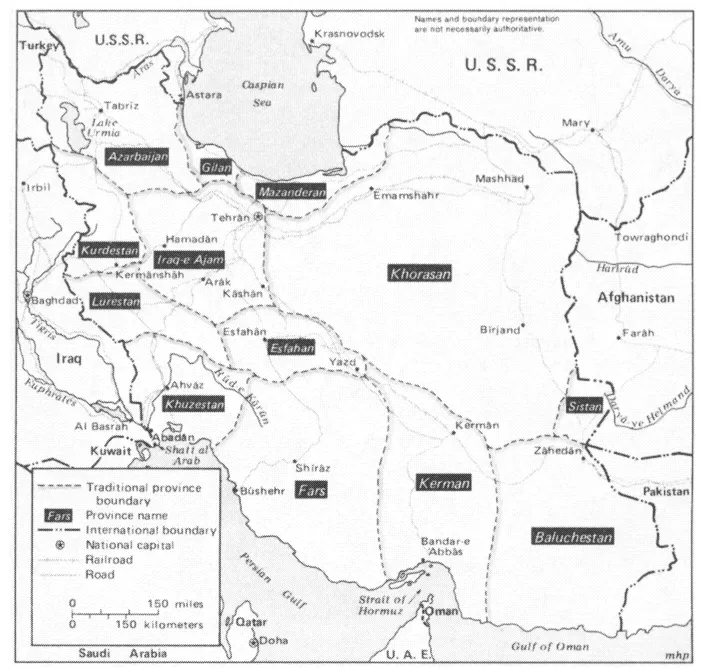

Map 1.1 shows the approximate frontiers of Iran-zamin, which includes peoples of many languages, religions, and customs and extends beyond the political boundaries of Iran into areas where non-Iranian peoples traditionally lived under Iranian political and cultural influence. On the west, the area identified as "Greater Iran" begins in the foothills of the highlands east of the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. In the northwest, the transition occurs in the Armenian and Kurdish highlands of eastern Anatolia. In the north, the frontier of Iran-zamin lies in the southern and eastern Caucasus and in the steppes and mountains of central Asia. The regions of Yerevan, Baku, and Shirvan (west of the Caspian Sea) and of Bukhara and Samarkand (east of the Caspian) are within this frontier. The eastern boundary lies in present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. The frontier is well-defined only in the south, where the northern shore of the Persian Gulf marks the beginning of Iran-zamin. (It could even be considered to include some of the gulf islands and coastal settlements on the Arabian Peninsula, where Iranian influences are strong.) In the southwest, Iran-zamin includes Khuzestan, that part of the Mesopotamian lowlands historically under Iranian rule.

MAP 1.1 Greater Iran: Periphery and heartland

The Heartland

As shown in Map 1.1, modern Iran includes almost all of the traditional heartland and parts of the periphery of Iran-zamin. Those artistic and cultural features historically considered "Persian" belong to the Iranian heartland, stronghold of the nation's culture—the home of the Persian language, Iranian Shi'ism (with its great shrines at Mashhad, Qom, and Shiraz), the ornate shahr-baf ("city-woven") Persian carpet, Persian painting and architecture, and traditional Persian town planning, gardens, and classical music. Within this area, too, are the monuments of the great Iranian empires of the past and most of the ancient Iranian cities, the setting for the nation's cultural life.

The Iranian heartland is a plateau, a region of mountains, deserts, and irrigated agricultural land. On the north, the Alborz (Elburz) Mountains divide the plateau from the coastal lowlands of the Caspian Sea and from the Turkoman steppe. On the south, southwest, and west, parallel ranges of the Zagros Mountains separate the heartland from the lowlands of the Persian Gulf coast and Khuzestan and from the mountainous tribal areas of Lorestan (Lurestan) and Kurdestan. To the east and southeast, the plateau region gradually merges into the highlands of Afghanistan and the deserts of Baluchestan.

The major physical features of this heartland plateau are its rim of mountain ranges and its interior basin of two great deserts, the Dasht-e-Lut and the Dasht-e-Kavir. Water from the surrounding mountains drains into the interior basins; what is not used for agriculture and settlements is lost in the deserts. The Dasht-e-Kavir, located in the north of the interior basin, is mostly saline mud covered with a hardened salt crust. The Kavir, which lies at an altitude above 3,000 feet, separates Isfahan (Esfahan) and the central province from Khorasan. The Dasht-e-Lut is an immense depression in the southern part of the interior basin. Ringed by mountains, its lowest part lies less than 1,000 feet above sea level. The Lut, a region of saltwater, sand dunes, and high winds, forms a difficult barrier between Kerman and the neighboring regions of Khorasan and Baluchestan.1

Two factors—terrain and water—have controlled the distribution of population in the Iranian heartland. Most settlement has been on communication routes and in agricultural areas between the mountains and deserts. Rainfall is generally insufficient for dry farming, so most farmers must rely on irrigation water; only the Isfahan region benefits from the water supply of a major perennial river, the Zayandeh-Rud. Other towns are located where the inhabitants could construct underground canals (qanats), using the existing slope of the land to bring water from higher elevations. This topography and irrigation method has confined permanent settlement to a relatively narrow band of territory between mountain and desert. Settlements too high on the mountain would be located above the qanat exit, and towns located too far from the mountains would be beyond the range of qanat water and exposed to encroachment of nearby deserts.2

Where water is available, settlement has occurred in a variety of climates, each having a characteristic agriculture and economic life. The sardsir ("cold lands") lie above 6,000 feet in northwest Fars, the western parts of Isfahan and Iraq-e-Ajam, and the mountainous regions of Khorasan. Typical sardsir agriculture consists of cereals, apples, plums, pears, melons, and walnuts. In the southern half of the country, usually below an elevation of 3,000 feet, lie the garmsir ("warm lands"). This climate is subtropical, and production of cereals gives way to citrus and dates in the lower valleys of Fars (Kazerun, Jahrom, and Darab), in the Tabas depression of Khorasan, and at Bam at the eastern edge of Kerman Province. Since climatic extremes in the sardsir and garmsir limit permanent agriculture, both regions are important areas of pastoralism and home to most of Iran's nomadic population.

Most of the major urban centers and agricultural areas of the Iranian heartland are located in the mo'tadel ("temperate") zone, at elevations generally between 3,000 and 6,000 feet above sea level. Teheran (Tehran), Isfahan, and Shiraz are all within this zone. Mashhad, in the northeast, is on the border of the temperate zone and the sardsir. Mo'tadel region agriculture includes cultivation of cereals, vegetables, and a wide variety of fruits including grapes and pomegranates. Since the climate is better suited to permanent, settled agriculture, pastoralism is relatively rare in this zone.

Map 1.2 shows the traditional provinces of Iran within the country's modern boundaries. On the great plateau, settlement and communication are delicately balanced between desert and mountain. Since communication routes had to avoid both extremes of terrain, the main roads linking the centers of major agricultural areas pass through transition zones between mountain and desert. The settlements north of the great salt desert, on the east-west highroad between Mashhad and Teheran, lie in one of these transition zones at elevations most suitable for bringing water by qanat from the neighboring Alborz Mountains. Towns such as Shahrud (now Emamshahr) and Nishapur lie in cultivated areas settled since early Islamic times, if not earlier. Although these modern cities do not always occupy the exact sites of the earlier towns, traces of older settlements are usually found within a few miles of the modern urban centers. The ancient "desert towns" of central Iran, such as Kashan, Na'in, and Yazd, are also balanced between mountain and desert. They are located on the northeastern side of the Zagros Mountains, where the combination of water and elevation allows permanent agriculture. The terrain permits easy northwest-to-southeast communication on a route between the central deserts and the mountains.

MAP 1.2 Iran: Traditional provinces

Settlement follows a different pattern in Fare, where parallel ranges of the Zagros Mountains divide the region into numerous narrow valleys. Elevation, not latitude, makes the climate of these valleys sardsir, garmsir, or mo'tadel. The broken, mountainous terrain and the absence of vast deserts and plains mean that wells, springs, and streams often replace qanats as the major source of water. Although there are perennial rivers in Pars (the Mand and the Kur), the major urban centers of the province have historically been located away from the rivers. The variety of climate and the mountainous terrain make Fars nomad country par excellence. The migratory tribes move from their winter quarters near the Persian Gulf to the summer pastures in the highland districts of Ardakan and Semirom. Most of these migrations take the nomads through or near Shiraz, the major city of the province. Although founded in early Islamic times as a military camp, Shiraz is now a transit point and market town for the nomads of Fars.

The mountainous topography of Fars has isolated its various settled regions and, with the exception of Shiraz, has kept the towns small. Settlement in Fars is not firmly welded to the pattern of desert, mountain, and qanat as towns grew as the political centers of regions important for their agriculture, their military position, or their location on a strategic trade route. Lar and Jahrom, for example, two relatively "recent" towns, grew in response to trade-route changes within the last six centuries. The recently (1971) completed Shiraz-Bushehr road has bypassed the ancient town of Kazerun, which may suffer because of this rerouting of traffic.

Iraq-e-Ajam, the region northwest of Isfahan, is another exception to the pattern of settlement determined by desert, mountain, and qanat. Mountain ranges surround high, spacious plains that are broken by low, irregular ridges. Relatively abundant rainfall permits dry farming on the open plains and in areas watered by mountain streams. Much of this area is sardsir; the major cities of Arak and Hamadan are famous for their cold winters and mild summers. The towns in this region are mostly centers of agriculture and transporation. Hamadan, one of the oldest continually inhabited sites in Iran, is located on the historic highroad from the Iranian plateau to the Mesopotamian lowlands.

The Periphery

Regions on the periphery of Iran-zamin, such as Azarbaijan, Mazanderan, and Sistan, have ancient historical links to the heartland, but the influence of Persian culture is weaker in these areas. The most obvious sign of this culture—the Persian language—disappears as a spoken idiom and is replaced by dialects of Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish, Baluchi, Lori, and Gilaki. The hold of Shi'a Islam also weakens in some areas of the periphery as there are numerous followers of Sunnism among the inhabitants of Kurdestan, the Persian Gulf coast, Baluchestan, and the Turkoman steppe.

Azarbaijan

Azarbaijan, with its rich agriculture, dense population, strategic location, and active trade and industry, is the most important of Iran's frontier regions. Historically, it has borne the brunt of foreign incursions into Iran by expansionist neighbors to the north and west—Romans, Byzantines, Turks, Caucasians, and Russians. The area has been a defense bastion, a guardian of Iranian tradition, a center of political activity, an economic center, and a stronghold of Shi'a Islam.

Azarbaijan is one of the most heavily urbanized regions of Iran, and the combination of its cold and temperate climates and its relatively heavy rainfall make it a productive area for cereals, dairy products, meat, fruits, and vegetables. It contains three major towns—Tabriz, Urumiyeh (Urmia, formerly Reza'iyeh), and Ardabil—and numerous small towns, such as Marand and Maragheh, which lie in prosperous agricultural areas. Azarbaijan is dominated by two mountain systems. In the east, about twenty miles west of Ardabil, the peak of Sabalan rises to 14,000 feet. Sahand, south of Tabriz, rises to 12,000 feet and provides water to settlements both north and south of the mountain.

The history of Azarbaijan has always been closely linked to the history of Iran. By tradition, it was the homeland of the prophet Zoroaster and the location of the holy fires that are so important in his religion. Alexander the Great never conquered the region (which was known to the Greeks as Media Atropatane), so it was less influenced by Hellenism than other Iranian regions. In the ninth century a.d., Azarbaijan was the center of a violent, anti-Arab and anti-Islamic movement called the Khorram-din, but Ardabil was the ancestral home of the Safavid dynasty, which made Shi'a Islam the Iranian state religion in the sixteenth century, and today Azarbaijan remains a stronghold of Iranian Shi'ism.

Although strongly Iranian in culture, present-day Azarbaijan is not Persian in speech. Following migrations of Turks into Azarbaijan in the eleventh century, almost all the inhabitants of the region, by a process still obscure to historians, became speakers of a Turkish dialect called Azari or Azarbaijani. The Azarbaijani language is spoken beyond the official boundaries of the provinces, in the town of Qazvin, which is about 75 miles west of Teheran, in villages around Hamadan and Saveh (about 80 miles southwest of the capital), and in some regions along the Caspian coast. The original Iranian language of Azarbaijan survives as the Tati language, which is spoken in isolated villages and in the Talesh hills near the southwestern corner of the Caspian Sea.3

Gilan and Mazanderan

Gilan and Mazanderan are the two provinces of the Caspian coastal region. This region, known in medieval times as Tabarestan, includes the coastal plain, which varies in width from two to thirty miles; the foothills on the north side of the Alborz Mountains; and the eastern slopes of the Talesh hills. Abundant rainfall and a temperate climate make this region unique in Iran for its greenery and forests. It produces all of Iran's tea, most of its rice, and is an important center of citrus, silk, and cotton production.

Although isolated from the Iranian plateau by the steep slopes of the Alborz, the Caspian region has always been important in Iranian history. Its unique climate, forests, and wildlife have earned it a special place in national folklore, and its productivity makes it a vital part of the Iranian economy. Because of its isolation, the Caspian region was less affected by the Arab invasions of the seventh century than the rest of Iran. The coastal lowlands were not conquered by the Muslims until the middle of the eighth century, and the highlands resisted the invaders for another 100 years.4 The mountains and forests of the Caspian region have provided its people with a refuge against outside invasions and cultural influences and have allowed the region's inhabitants to preserve their unique folk culture of languages, music, costumes, and cuisine found nowhere else in Iran.

The Turkoman Steppe

To the east of Mazanderan, the Caspian coastal plain gradually merges into the Turkoman steppe, a fertile region straddling the frontier of Iran and the USSR. This area, including the towns of Gonbad-e-Kavus, Bojnurd, and Shirvan, is inhabited by farmers and Turkoman horse nomads. The western part of this region is an open plain less than 500 feet above sea level, lying between the Alborz Mountains and the Atrak River. Farther east, the steppe is enclosed between two mountain ranges and reaches elevations of between 3,000 and 4,000 feet. In addition to its Turkoman inhabitants, Kurdish tribes, brought to the region in the seventeenth century, live in the east around Bojnurd.

Sistan and Baluchestan

Sistan and Baluchestan lie to the southeast of the heartland, separated from Kerman by the southern reaches of the Dasht-e-Lut. This area is characterized by low rainfall, high temperatures, scattered settlements, and poor communications. In Baluchestan the parallel ranges of the Zagros Mountains become irregular ridges in a desert terrain. The few small towns of this area are either on the coast—e.g., Minab, Jask, and Chahbahar—or, like Zahedan, at road junctions. The Sistan basin and its center Zabol lie less than 2,000 feet above sea level in an area that was once very productive but has recently suffered from severe drought. This region now supports only a limited amount of oasis agriculture, and much of the population has emigrated to more prosperous areas of Iran or to the Persian Gulf emirates in search of better economic opportunities.

The Persian Gulf Coast

The people living on the coastal plain of the Persian Gulf and on the southern slopes of the Zagros Mountains have traditionally remained very distant from the life of the heartland. Misrule, neglect, poverty, religious differences, and isolation have made these people culturally and economically closer to the Indian subcontinent and the Arabian Peninsula than to the Iranian plateau. Many Iranians consider coastal towns such as Bushehr and Bandar Abbas (Bandar-e-Abbas) to be places of exile. The gulf coastal plain and mountains are another of Iran's areas of refuge, in this case for Sunni Muslims living in the coastal towns and in the rem...