![]()

1

ROME AND OTHER CITIES

It was nothing new for emperors to consider and decide that Rome would not do any longer as the political and military centre of the empire. Panegyrists plaintively felt that Rome should once again become the imperial capital1 but there was no chance that this would happen. In consequence, there was a long pre-Constantinian history of the planting of imperial headquarters in other cities. As Herodian had already observed in the second century AD, ‘Where Caesar is, there Rome is.’2

Yet Rome was still all-powerful at that epoch. In the third century, however, Gallienus had established his headquarters at Mediolanum (Milan), when his father Valerian had gone east to fight the Persians.3 Mediolanum was conveniently equidistant from the northern frontier and Rome – and the location of major road crossings from the provinces – and northern Italy was more appropriate than Rome for combating the Germans on the Rhine and Danube. Rome was a long way away from them, and was easily cut off from the sea. For all practical purposes, therefore, the capital moved out of the city. The walls of Rome were greatly strengthened by Aurelian (270–5),4 but its role as political and miliary capital of the empire was over. ‘The old empire … of Rome and Italy as queen of the provinces was dead or dying.’5 It was not at Rome, for example, but at Mediolanum, that Maximian felt it necessary to rule;6 while his senior colleague Diocletian only visited Rome upon a single occasion, namely his twentieth anniversary (vicennalia)7 The ancient city, as capital of the empire, was already an anachronism.

And in 410 it was sacked, by Alaric I the Visigoth. The event appalled St Augustine. And it caused great distress to St Jerome, far away in Palestine.

I was so stupefied and dismayed that day and night that I could think of nothing but the welfare of the Roman community. It seemed to me that I was sharing the captivity of the saints, and I could not open my lips until I received some more definite news. All the while, full of anxiety, I wavered between hope and despair,

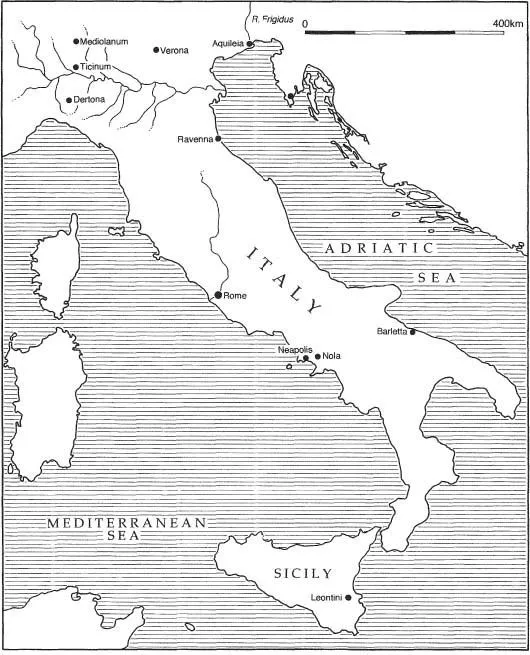

Map 1 Italy and Sicily

torturing myself with the misfortunes of others. But when I heard that the bright light of all the world was quenched, or rather that the Roman empire had lost its head and that the whole universe had perished in one city, then indeed ‘I became dumb and humbled myself and kept silence from good words.’8

The British or Irish theologian, or ‘heretic’ Pelagius was equally disturbed.

It happened only recently and you heard It yourself. Rome, the mistress of the world, shivered, crushed with fear, at the sound of the blaring trumpets and the howling of the Goths… . Everyone was mingled together and shaken with fear; every household had its grief, and an all-pervading terror gripped us. Slave and noble were one. The same spectre of death stalked before us all.9

Yet in spite of the disaster – and, Indeed, even after the final demise of the western empire In 476 – Rome remained highly privileged, and it was also still the spiritual and cultural and traditional centre of the world.

It remained the centre of western society, and its refugees were particularly vocal and influential Above all, Rome was the symbol of a whole civilization. It was as if an army had been allowed to sack Westminster Abbey or the Louvre… . Rome symbolized the security of a whole civilized way of life. To an educated man, the history of the world culminated quite naturally in the Roman empire, just as, to a nineteenth century man, the history of civilization culminated in the supremacy of Europe.10

In addition, Rome even now remained the home of the senate. But the character of that body had changed. It decided nothing – it was the emperors who decided everything; nor were they necessarily keen to be near the senators. These were largely rich landowners, who were, it is true, extremely Influential: though often they did not bother to come to the meetings of the senate at all, but stayed on their enormous estates. The tradition of their opposing the emperor still existed – and some emperors were afraid of it – but it had greatly diminished.

So if the rulers no longer ruled from Rome, where were they? ‘Where Caesar is, there Rome is’, as we have seen; and Caesar was in a good many different places. Mediolanum has already been mentioned: the new concept of imperial defence had also made Aquileia and Verona more important. It was right that Mediolanum (like Verona) should become a colonia Gallieniana,11 because Gallienus (253–68) was based there, making it his capital, as we saw. In 268 Aureolus was proclaimed emperor in the city12 (though he did not last). Aurelian (270–5) fortified Mediolanum at the same time as he built the walls of Rome; traces of his construction are still visible.13 Mediolanum was rising as a great political centre, largely because of pressure from the Germans, but also for the other reasons that have been stated. Maximian, it may be repeated, reigned there; and he abdicated there (305; for a time); Valentinian II (375–92) moved his court to the city. Ambrose was bishop of Mediolanum, and it was there that he won his great victory for the Church.14

But Mediolanum was not the only imperial centre in north Italy Aquileia and Verona have been mentioned, and Gallienus, when he established his residence at Mediolanum, had his military headquarters at Ticinum (Ticino), which, moreover, replaced Mediolanum as a mint under Aurelian (274). In 402 the emperor Honorius decided to establish himself at Ravenna, where there was landward protection from the marshes, and easy maritime facilities in case escape to the east became necessary

The later story of the monk Fulgentius is also illuminating.

One day in the year 500 the African monk Fulgentius, later bishop of the small town of Ruspe, fulfilled a life’s ambition in visiting Rome… .

Rome, centre alike of law and the tradition of human authority and of Christian orthodoxy and primacy, had beckoned to him. He had read in the pagan poets their eulogies of this city, elevated to the status of a goddess, to be revered and justly revered throughout the world. But what he saw amazed him. “How wonderful’, he is said to have exclaimed, ‘must be the heavenly Jerusalem, if this earthly city can shine so greatly!’15

For Rome was the centre, the city, the lawgiver, the fact that had dominated and made the world men knew. From Iraq to Wales, from the Baltic to the Sudan, she had fashioned and left all in her image. On the countryside her language had left the place-names men used; in the towns men lived by her organization, her law, her peace. ‘What was once a world, you have but one city’, a poet of the previous century, Rutilius Namatianus, had declared.16

The good monk, from the small white towns on the edge of the desert … could yet know that he was at home. All this was the work of time. Rome was now in the thirteenth century of her foundation, and in the eleventh of her domination, a matter to move men’s minds in awe.17

For one thing, Rome was the headquarters of the Pope, who now became increasingly important. And, as we have seen, it was still the meeting-place of the senate.

Another very important centre in the west was Augusta Trevirorum (Trier) on the River Mosella (Moselle). Not only was it the capital of the diocese (group of provinces) of Gaul, and residence of the Prefect, containing one of the best universities of the west (attended by St Jerome), but it was the capital of Constantius I Chlorus (305–6), who contracted for the construction of his fleet there, and it remained the capital of his son Constantine I the Great until 312; then he moved to a fifty-room villa-palace on the Mosella, five miles out of the city. Subsequently, Augusta Trevirorum still figured as an imperial town for at least another century.18 Valentinian I (364–75) made the place his headquarters for operations against the Germans, and his son Gratian (c. 380) lived there.

During the same period Arelate (Constantina, Aries) also became more important;19 Constantine had lived in that city as well, in addition to other places. One of them was Naissus (Ni§), where he had probably been born. He often visited the town later, and erected splendid buildings within its precincts. It was probably the earliest permanent military camp in Moesia, possessing great strategic significance.

In 314–15, however, Constantine had moved his headquarters to Sir-mium (Sremska Mitrovica),20 which was a road junction and the most important strategic centre of the Danube region, containing arms factories, a fleet station and an imperial mint. It had been, for a time, the residence of Marcus Aurelius (161–80) and Maximinus I Thrax (235–8) and others. Claudius Gothicus (268–70) mopped up the Goths from his base at the imperial palace at Sirmium, which was also where he died. Possibly Aurelian (370–5) came from the place, and it profited from the encouragement of grape-growing by Probus (276–82), who had been born there.21 Maximian was a peasant’s son from Sirmium, and his senior colleague Diocletian spent much time at the place, promulgating numerous laws. Galerius resided for a long time at Sirmium; it was his ‘favourite city’22. Constantine, too, moved his administration from Augusta Trevirorum and Mediolanum to Sirmium, and he had seriously thought of giving his name to the last-named town, if his first war against Licinius23 had proved decisive (which it did not). It was from there, perhaps, that Licinius promulgated the Edict of Milan, published at Nicomedia 24

But subsequently Constantine, who transferred his headquarters from one place to another – including Thessalonica (Salonica), which was strong and had served as a capital25 – moved from Sirmium to Serdica (Sofia) (317/18). He liked the Balkans, because the region was pivotal for the army; he enlarged the already existing palace at Serdica, and seriously considered the place as a possible imperial capital, declaring that it was his Rome.26 But Serdica had disadvantages as well as advantages, and Constantine finally opted for somewhere else.

He did not fancy going out of Europe, because of the threat from the Germans. So the ancient and wealthy cities of Antioch and Alexandria did not attract him, despite their imperial connections, intellectual ferment, and loud noises regarding ecclesiastical affairs.27 Nor did Nicomedia (Izmit), which had been the capital (and place of abdication) of Diocletian; and Galetius, too, had resided at Nicomedia. It had a great deal in its favour, including a good harbour, large fertile territories, and a position on the trunk road from the Danube. But it was too far away from the northern frontier, being in Asia Minor; and there were other things against it too.28 Its position has been estimated as follows:

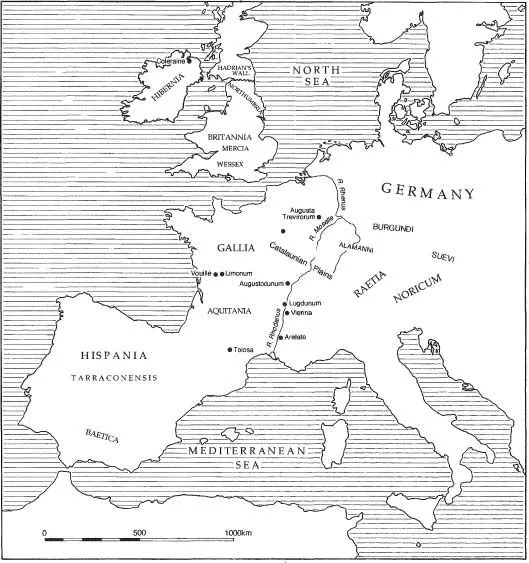

Map 2 The western provinces

The dawn of late antiquity even saw it [Nicomedia] become capital of the Roman empire, a role it was to maintain for a generation. Events of the fourth century, however … brought this moment of glory to an end, as the city resumed its old role as a major provincial centre… . The foundation of Constantinople, only sixty miles away, sealed the fate of Nicom...