Scholars have long lamented the tenuous connection between normative claims and empirical facts in the transitional justice field. The lack of theorising, the posing of unverified claims as universal truths, the muddled and inconsistent use of terms and variables, and the mixing of causes and consequences are but some of the valid criticisms that have surfaced in recent years. A decade ago, David Mendeloff (2004) warned against overstating the importance of transitional justice in post-war reconstruction. Similarly, using the war on the Balkans as her empirical backdrop, Jelena Subotic correctly notes that the most serious failing of the transitional justice literature is ‘the lack of serious theorizing about the causes and consequences of many of these [transitional justice] projects’ (2009, 25). Paul Gready, basing his analysis on the case of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, questions whether claims about transitional justice effectiveness ‘are backed up by evidence’ (2010, 5). Drawing on their empirical experience of transitional justice processes in different parts of the world, these scholars, and many more, draw attention to the same crucial question: Does transitional justice really matter – or do we just assume that it does?

Building on the emerging literature, this book asks how we can most effectively assess the impact of various transitional justice initiatives on complex social processes such as democratisation and peacebuilding. We define transitional justice as processes and mechanisms for dealing with past atrocities, covering a range of formal as well as informal mechanisms developed in post-authoritarian and post-conflict situations, including prosecution through courts, truth-telling through truth commissions, victims’ reparations, amnesties, vetting, lustration, institutional reform, and memorial projects. 1 While transitional justice has long been emphasised as a route to peace and democracy after conflict, there are still many unsubstantiated claims and conflicting findings in the literature regarding the impact of various transitional justice mechanisms (TJMs). The reason is partly the inherently complex set of causal relationships and varied real-life situations, which are seldom captured in a literature based mainly on single-case studies or large-n studies. Specific country experiences make for weak generalisations, while quantitative studies generally lack sensitivity to context and therefore tend to oversimplify their findings.

To start filling this gap in the literature, this book develops an analytical framework for understanding the impact of transitional justice on the larger societal goals of peace and democracy. It focuses on four central TJMs: trials, truth commissions, reparations, and amnesty laws. 2 The book examines the importance of the national, regional, and global contexts and of other key factors such as ‘world time’ for the outcome of transitional justice processes through stringent comparative analysis in a small-n study. The four case studies of Uruguay, Peru, Rwanda, and Angola were chosen from different categories of current transitional justice cases (post-authoritarian, post-conflict, and mixed) and from two regions (Latin America and Africa) where many transitional justice processes have been launched since the beginning of the 1980s.

The case studies address several questions. How does context matter for understanding the performance or impact of transitional justice processes in post-authoritarian or post-conflict situations? How and when do the multiple cross-cutting (and sometimes contradictory) goals and processes of transitional justice help enhance peace and strengthen democracy? Conversely, under what circumstances is it likely that allowing massive crimes to go unpunished will undermine the prospects for peace and democracy? These are not only theoretical and normative questions, but also very practical concerns of politicians, practitioners, and donors. When countries such as Colombia, Sudan, or the Democratic Republic of the Congo grapple with how to end a violent conflict without erasing accountability for past crimes, what models or lessons can they build on?

Transitional justice impact: the claims

There has been plenty of wishful thinking with respect to what transitional justice processes can and should achieve. Claims are made regarding the expected impact of individual TJMs on truth, justice, and reconciliation, on the one hand, and on long-term societal peace and democracy, on the other. As we will show, some of these claims are purely normative. Some are philosophical. Only a few are empirically grounded.

The overall assumption in the literature is that transitional justice plays an important role in transitions from authoritarian rule to democracy, or from situations of armed conflict to peace. However, the dominant views on impact have changed over time, reflecting important shifts in international factors such as prevalent human rights norms and practices and an expansion of the transitional justice toolbox. This has taken place over the course of what Ruti Teitel (2003) usefully refers to as the three phases of transitional justice. Phase I, between the end of World War II and the onset of the Cold War, was characterised by interstate cooperation, war crimes trials, and sanctions, as seen in the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials. Then came a period of almost four decades with little or no transitional justice. Phase II, the post-Cold War phase, coincided with the ‘third wave of democratization’ (Huntington 1991). The transitional justice discourse expanded from an almost exclusive focus on legal responses, intended primarily to ensure the rule of law, to a more diverse focus on ‘truth’ and ‘justice’, with reconciliation as a desired outcome. This period saw diversification of the formal mechanisms employed to bring about transitional justice, including a series of non-legal mechanisms such as truth commissions.

In Phase III, the current phase, transitional justice has become an established component of post-conflict processes. Discussions of transitional justice frequently begin even before a conflict has ended. A particular feature of this phase is an increased interest in local or traditional processes of justice and reconciliation. Another feature of the third phase is diversification of actors: in addition to local actors, including ordinary citizens at the grassroots level, there has been a proliferation of donors eager to contribute to a ‘justice cascade’ (Sikkink 2011). Human rights and international legal norms are increasingly cited by both academics and practitioners.

The transitional justice literature was initially dominated by legal scholars and political scientists. More recent contributions from philosophers, anthropologists, criminologists, sociologists, historians, psychologists, and development scholars, among others, have made the field truly interdisciplinary. As a result, the discourse has become increasingly complex. From an initial focus on retributive justice and the rule of law, the discussion of transitional justice has broadened to include other elements such as the meaning of key concepts (e.g. truth, justice, reconciliation) and the relationships between them, as well as methodological issues involved in evaluating the impact of transitional justice.

More recently, the scholarly debates have shifted from a principal focus on normative claims to an increasing concern with their empirical verification. Which mechanisms work – if any – is a question raised by academics as well as by practitioners and donors. As more and more money pours into transitional justice, and as more and more actors enter the field – including non-governmental organ-isations (NGOs), transitional justice programmes, and activist networks – the concern with measurement and usefulness of transitional justice has grown apace.

In spite of growing concern with impact, the scholarly literature remains largely dominated by unsubstantiated claims about the positive consequences of various processes. Among the outcomes, the three meta-goals of truth, justice, and reconciliation – which have been aptly referred to as the ‘triumvirate’ of transitional justice (Gready 2010) – dominate the literature. Claims regarding the relationships between these three overarching goals have shifted over time, as have the claims about the links (and possible tensions) between the immediate goals of ‘truth and justice’, on one hand, and the long-term goals of ‘peace and democracy’, on the other (Leebaw 2008).

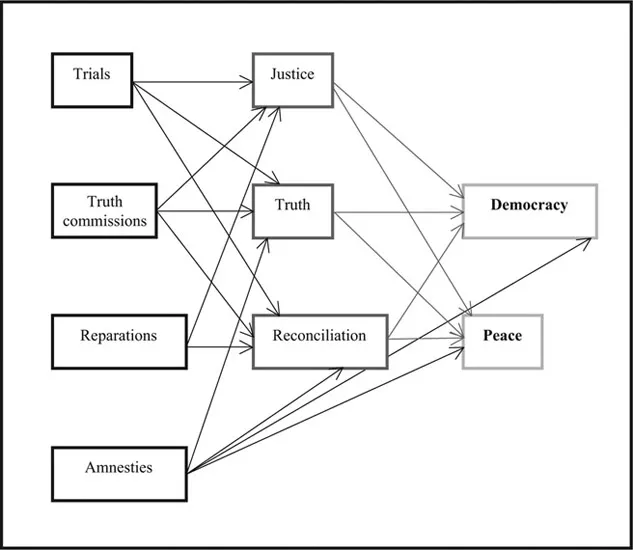

Each of the four central mechanisms examined in this book – trials, truth commissions, victims’ reparations, and amnesty laws – is commonly associated with a series of objectives and goals (Figure 1.1). Taking this as the starting point for our analysis, we position the four transitional justice mechanisms in the left causal field and explore their impact on peace and democracy via three intervening variables: justice, truth, and reconciliation. Critically examining the claims implicit in these pathways is the task of this book. As Figure 1.1 shows, some impact seems to flow directly from the individual TJMs to ‘peace’ and ‘democracy’ (terms that we deliberately leave undefined for now). Other kinds of impact are assumed to flow via the intervening variables.

Figure 1.1 Claims associated with transitional justice mechanisms

Figure 1.1 does not provide an exhaustive list of potential causal links. Both the order of variables and the potential links between them are open to dispute. We have consciously grouped ‘justice, truth, and reconciliation’ together and ‘democracy and peace’ together. Other scholars might argue that peace must come before reconciliation or that justice and peace should go together. 3 The arrows illustrate only a selection of the potential causal connections between individual transitional justice mechanisms and their main anticipated or hoped-for achievements.

The causal field is, as noted above, complex, and it is not obvious what leads to what. For a start, transitional justice mechanisms are not the only factors that contribute to peace or democracy, nor are they necessary to bring about these transitions. Economic development and regional stability, or their absence, are among the many factors that affect democratisation and peacebuilding processes. Arguably, electoral democracy can be established and survive in the aftermath of dictatorship and war without the adoption of TJMs – as in Spain, Portugal, and Mozambique. Similarly, we have seen in several cases that short-term peace, in the sense of an absence of fighting and violence, can be achieved after civil war through a peace agreement that is respected by both parties, even when transitional justice is not part of the peacebuilding package. However – and this is a hypothesis of this book – to ‘mend the social fabric’ of society and achieve what we will later refer to as ‘positive peace’ in the long term may require different mechanisms or tools, such as transitional justice. The international community and donors today certainly believe that implementing transitional justice in contexts of political and democratic transitions is a good thing. There is often a big international push for transitional justice when countries are emerging from conflict. One of the questions we explore is whether and how transitional justice mechanisms feed into and strengthen the processes of democratisation and peacebuilding.

Below we identify the principal claims in the causal pathways outlined in Figure 1.1. Many of the claims regarding impact that are based on moral assumption and normative preferences, prevalent in the early years of transitional justice, have given way to more empirically based claims, often linked to a specific country’s experience with transitional justice. The overview is not exhaustive but illustrates the frequently contentious nature of the impact claims that flourish in the field. 4

Claims for the impact of trials on democracy and peace

Scholars and practitioners who support trials for gross human rights violations consider criminal accountability to be necessary or desirable for complex moral, legal, and institutional reasons. Supposedly, punishment creates accountability, restores justice and dignity to the victims of abuse, establishes a clear break with past regimes, contributes to reconciliation, demonstrates respect for democratic institutions (particularly the judiciary), and (re-)establishes the rule of law, thereby helping to ensure that similar atrocities will never happen again. If hideous crimes go unpunished, it is claimed, people in newly established or re-established democracies will be unable to trust the state in g...