eBook - ePub

The World of Words (Routledge Revivals)

An Introduction to Language in General and to English and American in Particular

- 354 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The World of Words (Routledge Revivals)

An Introduction to Language in General and to English and American in Particular

About this book

First published in 1939, this book provides a brief but comprehensive view of language in general, and of English and American language in particular. It is suitable for beginners and those who wish to learn about the basics of linguistics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The World of Words (Routledge Revivals) by Eric Partridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter I

Families of Languages

SO long ago as 1822, that great German thinker and linguist, Wilhelm von Humboldt, stated, and exactly a century later Otto Jespersen, the famous Danish writer on language, repeated, that languages are so different in form that it is impossible to classify them both accurately and comprehensively, or to divide the languages of the world into groups or families in such a way as to account satisfactorily for absolutely all of them.

That is true. But we can, after all, account satisfactorily for most of them; and this 'most' includes all the important languages. So why despair? No method of grouping, no 'system of classification' (as the learned prefer to call it) is, because no method can, for certain, be perfect or complete: but the fact that we cannot get £1,000 is a poor reason for refusing £900: we must make the best of what is available, in languages as in life.

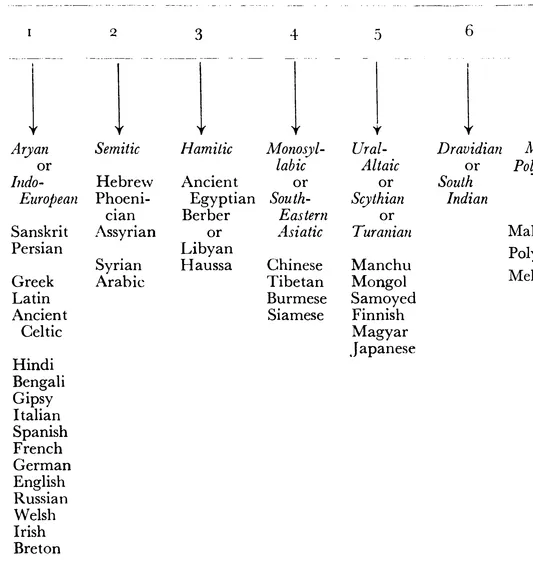

Originally there may well have been only three or four languages in all; it is barely possible, though extremely improbable, that there may have been one language and one only. But we have no proof that there were ever so few as even three or four languages. It is easy to theorize—to build up all sorts of wild ideas—when there are no facts to contradict us. If, however, we keep to the facts and hold fast to what is known, we see that there are either thirteen or fourteen linguistic groups, thirteen or fourteen families of languages. It is not to be assumed that the various members of any one family do not, as it were, stand on their own feet: do not possess certain perhaps very important qualities and defects that are theirs alone: are not as individual as the persons forming an ordinary family. We do not deny but emphasize the strength and the reality of a human family when we point out how individual is each member of that family. In the same way, we do not lessen the reality and the usefulness of a linguistic family if we admit that there is a great deal of truth in Humboldt's opinion that each separate language and even the lowliest dialect1 should be looked upon as a whole with a life of its own; that each language, each dialect, is different from all other languages or dialects; that it expresses the character of the people speaking it; that it is the outward expression of that nation's soul; and that it points to the particular way in which that nation tries to reach its ideal of speech—a speech that, to the nation concerned, seems to be the best it can have. But some (often many) words in a language are thrust upon that language from outside or inherited from a people once related to it or connected with it: and these words form one of the means by which we are enabled to divide languages into groups and discover which are the members of a family.

To relate precisely how these groups have been arrived at, how these families have been gathered together, lies beyond our scope: for the excellent reason that such a relation can be readily understood only by those who have an advanced knowledge of philology (or linguistics), as the science of language— that body of knowledge which concerns the speech of human beings—is generally called. It is best for the younger, as for the less erudite, among us to take for granted the various reasons for the grouping of the world's languages into groups or families: but that there are families of speech is certain. The older we are or the more deeply we think, the more clearly do we see that it is both a convenience and a necessity to assume that, so far as has been discovered, certain things are facts—certain things are true: it is neither bluff to assert nor folly to believe that there are facts: in language generally and in languages particularly.

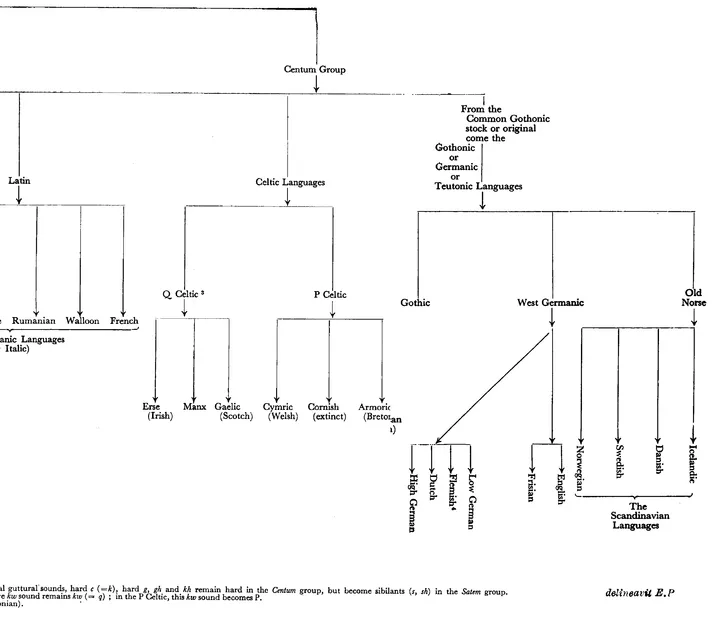

It is, on the other hand, well to note that variation in speech, differences in language, are a result of the movements of population and the migrations of peoples. There may originally have been one race upon earth; more probably there were several or many races or primitive nations. They, like the later racial divisions and communities, have, 'from point to point through the whole life of man on the earth', not only 'spread and separated' but jostled against or interfered with one another; have 'conquered and exterminated' 1, or conquered and absorbed, or mingled with one another and thus formed new units: and these spreadings and separations, jostlings and interferences, conquests and peaceable minglings have had a tremendous influence upon the various languages of the races affected. So long as evidence of original unity is discoverable, we speak of the languages concerned as being 'related' and combine them into a family. A family of languages is simply a group of languages that have descended from 'one original tongue'. Now 'of some families we can follow the history . . . a great way back into the past; their structure is so highly developed as to be traced with confidence everywhere; and their territory is well within our reach. . . . But these are the [comparatively] rare exceptions; in the . . . majority of cases we have only the languages as they now exist.' (See the first diagram.)

Yet, to digress for a moment, a classification of languages is not precisely the same thing as a classification of races or nationalities. Languages are, in many ways, as much institutions as a country's religion or its law is an institution. Languages can be, sometimes

I. THE FAMILIES AND THEIRE OF LANGUAGES OF MEMBERS

are, transferred: circumstances force them to be transferred. 'Individuals of widely differing races are often found in one community: yet they all speak the language of that community. The most conspicuous example ... is that of the Romanic countries of southern Europe'—Italy, France, Spain, Portugal— all using variations of a language that, '2,500 years ago, was itself the insignificant dialect of a small district in central Italy'; it is only fair to add that the inhabitants of that district, the Romans, were a people so remarkable that they have changed the whole history of Europe. 'Such are the results of the contact and mixture of races and languages. . . . Mixture of race and mixture of speech are . . . connected processes; the latter never takes place without something of the former; but the one is not [an exact] measure of the other, because circumstances may give to the speech of the one element' or part 'of population 'a power and a widespread use quite out of proportion with the size of that element of population—as we have seen it do in Italy. There remains in French only a small trace of Celtic, at one time the language of the most populous and important people in Gaul or France; French as we know it is, in the main, a modern form of the language spoken by 'the Latin conquerors of Gaul'; French was adopted by the Normans, who were originally Norsemen; these Normans conquered England, and their language became mixed in with Old English (or Anglo-Saxon as it is still called not very accurately)—but that mixing is another story, told, as it happens, in the next chapter.

To return to the groups of speech, the families of languages. Such a classification is a classification of languages only, although it may, and often does, also throw light on 'movements of community', movements that, in their turn, 'depend more or less upon movements of races'. And it must be remembered that language families as important as some of those set down here may have disappeared; certainly some families remain in a very incomplete form.

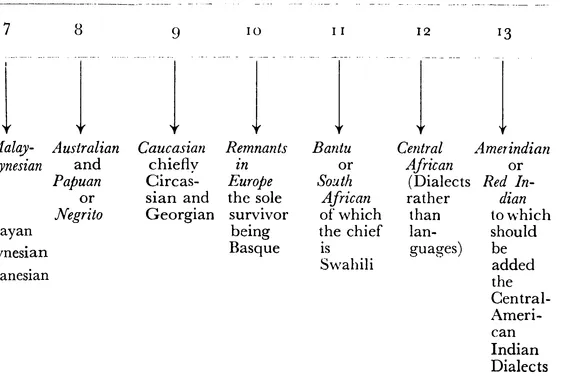

I. By far the most important family is the Indo-European 1 or, as it used to be called very inaccurately by over-ambitious German philologists, the Indo-Germanic; some prefer to call it the Aryan family. This group includes virtually all the modern European languages, as well as Greek and Latin and Ancient Celtic; and the Asiatic Indian languages (Hindi, Bengali, original Gypsy), themselves related to Persian; Sanskrit (often spelt Sanscrit), the easternmost, and oldest, known member of the Indo-European family; Armenian; Russian and allied languages; Albanian.2 To this 'family' belong those nations who have, for many centuries, been the leaders in the history of the world; its literatures, especially in modern times, are among the greatest; the records of its achievements are the fullest; its development has been much the most varied, much the richest. These 'advantages3 have made Indo-European language the training-ground of comparative philology' (the study of various

II. THE INDO-EUROPEAN (OR ARYAN) FAMILY OF LANGUAGES

languages in their relation one with another), 'and its study will [probably] always remain the leading branch of that science

2. Undoubtedly second in importance is the Semitic group, comprising Hebrew1 (the language of the Bible and the Talmud), Syrian and Assyrian, Arabic, Aramaic, Phoenician. This family may originally have been part of the Indo-European family, but this conjecture has not been incontestably proved. The Semites were that ' race of mankind which includes most of the peoples mentioned in Gen[esis], x, as descended from Shem, Son of Noah' (The Shorter Oxford Dictionary).

3. The Hamitic family, of which easily the most important member is ancient Egyptian; the Berber (or Libyan) languages of northern Africa; the Ethiopic languages of eastern Africa, including Haussa —a language spoken in the Sudan and even more valuable than Swahili (in group n) as a means of communication in Africa. This family bears certain resemblances to the Semitic: therefore Hamitic, Semitic, Indo-European may all have been, originally, dialects of the one language, or rather some one primitive language may have branched off into these three. The name comes from Ham, the second son of Noah.

4. The Monosyllabic Group or South-Eastern Asiatic family. The leading member...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Part V

- Appendix: Phonetic Symbols

- Index