![]()

1

Introduction and conceptual considerations

This book is about European societies, their structures and change. The main objectives are to describe contemporary European societies along a broad range of dimensions, highlight commonalities as well as variations, understand processes of integration and characterise the ongoing transformation of the European social space. To talk about European societies in the plural means that we not only focus on European unity or ways to achieve it, as some scholars do, but view European societies as national and European at the same time. However, we emphasise that within the European context, and particularly with the nascent European polity, national societies have been challenged and transformed fundamentally and are no longer independent entities, but closely interwoven and connected.

Taking the national and European context into consideration poses a true challenge. Most research on patterns of social change, inequality and social stratification focuses on nation-states. Core concepts of research on social stratification, for example, class, profession, income distribution, mobility and education, have been developed within the framework of the nation-state and national society. By the same token, Favell (2007: 122) states that most sociological research is still wedded to national society and that it seems to be ‘very difficult to systematically study pan- or transnational social structures, because of the way nation-states have carved up the world and its populations, statistically speaking’. However, as a result of processes of European integration, globalisation and internationalisation, the world of European nation-states has been shaken up. Hitherto focused on national societies, social science is not equipped to do justice to these processes, and this is particularly true for the process of Europeanisation. Sociology as a whole, and research into social stratification and inequality in particular, have therefore been accused of ‘methodological nationalism’ (Agnew and Corbridge, 1995: 122), since they unquestioningly assume a congruence of territorial, political, cultural, economic and social boundaries:

The methodological nationalism of the sociology of inequality and research on the welfare state is as obvious as the self-containing relation between these two sociological disciplines. The basic assumption is the nation-state as the basic unit of social conflicts and their regulation by the state, generally without giving a singly thought to the presuppositions which guide research.… Thanks to this analytical mindset, this kind of theory and research is blind to Europe. The result is the failure to appreciate that the mixing, blurring and redrawing of boundaries between Member States, and also between Europeans and their others, has far-reaching implications for the pan-European conflict dynamic – for the question of recognition, social inequality and societal redistribution. Likewise the problems and dilemmas resulting from the intersection of these issues are not appreciated. (Beck and Grande, 2007: 174)

In this textbook, we will argue that the European Union is an important frame of reference for analysing European societies. Through European integration, that is, through exchange, integration and the development of new forms of solidarity and conflict, a new space of societal relations is being created, redefining fields of activity that previously fell within the compass of the nation-state (Heidenreich, 2006a). The EU is not just an intergovernmental arrangement for the harmonisation of markets, but also a supranational entity sui generis, which has major social consequences for the lives of people in the member countries and their chances of prosperity. As Medrano (2008: 4) puts it:

The new European Union has a tremendous impact on the lives of Europe’s citizens, whether they know it or not. The European Union is a multi-tiered polity, where government competences are distributed or shared by European, national, and subnational institutions. It is thus worth exploring what impact these dramatic institutional transformations have had on Europe’s social structures rather than focus exclusively, as political scientists have done so far, on the impact of European social structures on the institutionalization process of the European Union.

A comprehensive sociological description of overall societal interdependency, a description of the social, economic and political effects of the unification process on the development of a European society and its social structure, remains a desideratum of sociological research. Systematic research on the Europeanisation of national societies as well as on Europe as a whole is lacking. What is also needed, moreover, is a sociological approach to the EU and Europe that not only focuses on culture and social theory, but would ‘reintroduce social structural questions of class, inequality, networks and mobility, as well as link up with existing approaches to public opinion, mobilization and claims-making in the political sociology of the EU’ (Favell and Guiraudon, 2009: 550).

The Europeanisation of societies is something fundamentally different from the globalisation processes affecting national societies. Europe, or more specifically the European Union, appears as a new level of aggregation, which, while not superseding nation-states, produces new forms of vertical and horizontal integration. Populations once isolated from each other now come into frequent contact. Borders are being deinstitutionalised and goods, services, capital and people can circulate freely. Labour markets are being Europeanised and educational institutions standardised. The European Union is also developing regulatory and redistributive forms of intervention. Whereas the globalisation perspective assumes that the scope for government action influencing the distribution of wealth and life chances is shrinking dramatically, research on Europeanisation is focusing on a new structuring formation situated between the nation and global society (Delanty and Rumford, 2005; Bach et al, 2006; Hettlage and Müller, 2006; Beck and Grande, 2007; Fligstein, 2008; Outhwaite, 2008; Eigmüller and Mau, 2010; Immerfall and Therborn, 2010). Every social scientist who examines the case of Europe must ask herself what the appropriate concepts, parameters and indicators are for a survey of European societies. Two alternatives present themselves: either one takes the individual Member States as the appropriate level at which to study social inequality and social structuration and then adopts a comparative perspective, or one refers to Europe as a whole, meaning that Europe is understood as a specific entity to be compared with other macro-societies.

Since the mid-1990s, analyses of social structure in Europe have been predominately comparative (see also Therborn, 1995; Hradil and Immerfall, 1997; Boje et al, 1999; Crouch, 1999; Immerfall and Therborn, 2010). These approaches are united by the attempt to identify the similarities and differences between European societies. In recent decades, comparative researchers and the reporting system of the European Union have compiled a substantial body of data that makes it possible to compare quite different aspects of European societies. Empirical research provided by, for example, the Eurobarometer (EB), the EU-SILC data, the European Social Survey (ESS) or the European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS) has fostered a standardisation of research instruments and thus improved comparability. In addition to these comparative approaches, in the future it will become increasingly important to examine the reciprocal effects and interactions between and across European societies (Kaelble, 1987, 2005; Fligstein, 2008). This is the perspective adopted by transnational approaches to research on Europeanisation. The main thrust of transnational approaches ‘is to identify processes and dynamics that occur in several societies and are therefore “transnational” or European. Such processes of Europeanization will in general refer to new state–society relations, especially the interconnected nature of societies’ (Delanty and Rumford, 2005: 8). They deal with the question of the extent to which, through the elimination of borders and supranational integration, a new space of social interaction is being created, so that national social structures can no longer be viewed as isolated and independent units. On the one hand, we understand the Europeanisation of national societies as referring to the process of integration and interaction between national societies; on the other hand, it refers to the process of convergence of European societies, brought about and influenced by the process of European integration.

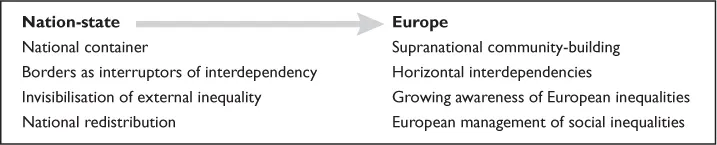

European integration, therefore, can also be described as a process by which national societies become interconnected and also build a supranational community (Figure 1.1). In the economy and politics, European integration processes are increasingly limiting the freedom of action of nation-states. Yet in the societal realm, nations are growing and interacting more closely at the level of collective actors, social groups and individuals. In addition, the European Union has itself become a political player in the arena of redistribution, managing intra-European social inequality through its regulatory and distributive measures. Finally, frames of reference are also shifting when it comes to evaluating and addressing inequality in the allocation of resources and in social positions. The context of relationships in which people and groups situate themselves is broadening. As a result of European integration, the perceptual barriers that previously obscured inequalities among countries are disappearing and Europe is becoming a frame of reference for the perception and comparison of inequality and social development. The dismantling of borders does not diminish the problem of inequality: ‘rather conflict threatens to flare up because the perceptual barriers to comparing different national situations are being removed, so that equal levels of inequality can be assessed equally and corresponding adjustments can be demanded’ (Beck and Grande, 2007: 177).

Against this background, research into societal structures and change clearly must take account of the Europeanisation of European societies, which includes the various forms of interdependence and interactions among national societies, the similarities of traditions and social and cultural resources, as well as the question of new, specifically European, lines of conflict and tension, which can no longer be understood by referring solely to the nation-state (Vobruba, 2005; Beck and Grande, 2007; Fligstein, 2008; Haller, 2008; Outhwaite, 2008; Rumford, 2008, 2009).

This textbook constitutes a first attempt to present the social structure of Europe comparatively, at the same time taking into account the growing interdependence among European societies – of course without claiming to be able to offer a complete picture of a self-contained object of study.

Now with 27 member countries and nearly 500 million people, the majority of the countries and inhabitants of Europe are integrated into the European Union as a form of supranational community. It therefore seems justified to us to delimit our object of enquiry, namely European social structure, primarily on the basis of the current territorial area and membership of the European Union. The systematic inclusion of all member countries of the EU makes it possible to delve more deeply into differences in the East–West comparison than is the case in many publications that focus primarily on Western Europe. Readers will notice that the data in individual subsections are of varying quality. Data gathering in official, administrative circles and in the social sciences seldom deviates from the nation-state as the main object of enquiry, and forays into the analysis of European social structure are still in their infancy.

The book is divided into three main parts. We begin with a historically oriented section, which deals with issues of territorial and social order in Europe. We show how the geographical boundaries of Europe were constituted and how they have changed over time. At the same time, we trace the relationship between territorial expansion and the European population. In this historical process, Europe did not in any way present itself as a uniform and homogeneous macro-order, but rather as a horizontally segmented entity. Of decisive importance in this respect was the nation-state model of integration. This notwithstanding, one finds in Europe a broad range of commonalities and forms of exchange. For instance, one can identify a European model of industrial society, with specific social structures, with typical institutionalised forms of the relationship between the state, market and family, and specific forms of social classes and class compromise. Horizontal interconnections and the emergence of similar social structures provide the basis for seeing Europe as more than a random arrangement of geographically adjacent countries.

In the second part of the book, we adopt a comparative perspective. First, we turn our attention to different institutional arrangements in Europe, examining the organisation and design of institutions of social policy, education and industrial relations. We then compare EU countries in terms of their demographic structure – that is, population and age structure, fertility and mortality rates, and family structures. A further chapter is devoted to the changes in social structures caused by migration, and examines patterns and systems of migration. In the chapter on the labour market, we look at economic development, labour-force participation, unemployment, sectoral and occupational changes, as well as mobility in the EU labour market. This is followed by some considerations on inequality in education in Europe, and we then look at the classic parameters of social inequality such as income, gender-specific inequality, wealth and poverty. In the final chapter of Part Two, we present selected aspects of the quality of life in European countries from a comparative perspective.

The third part focuses on recent societal developments in the context of European integration. Although European integration is originally a political project, it strongly affects society, including the living conditions and life chances of individuals, and links together national regimes of inequality. At the beginning of Part Three, we present the institutional and political framework of European integration. In the subsequent chapters we explore new structures of social inequality and conflict that are emerging in the course of Europeanisation. Moreover, we examine the forms and density of horizontal Europeanisation, that is, the ways in which a European space of experience and social interaction is being constituted. In a final chapter on ‘Subjective Europeanisation’, we discuss the role played by the European Union or Europe in the minds of the people.

![]() Part 1

Part 1

The European social model from a historical perspective![]()

2

Commonalities and intra-European exchange

European integration derives its power and legitimacy from Europe’s shared history, geographical unity, common cultural achievements, similarities in society and politics, multiple forms of solidarity and exchange, and shared values. The often-vaunted ‘unity in diversity’ refers precisely to this common foundation, which is the basis of the integration process. In the following sections, these areas of commonality will be presented and discussed. We begin with the borders of Europe and their different interpretations, which is still among the most delicate issues in the process of European integration. We will also describe the internal and enduring disparities that have developed in the social and economic space of Europe. Next, we describe shared values in Europe, which form the basis for conceptions of integration and amalgamation. In the third section, we examine networks and interconnectedness within Europe from a historical perspective. We will argue that Europe, despite all its turmoils, has always been a space of social communication and exchange.

2.1 Territoriality, borders and internal structuration

Historical border demarcations

Determining the borders of the European continent is no easy task, as ‘Europe has been mapped by numerous borders, both internal and external’ (Delanty and Rumford, 2005: 31). From a historical perspective, one can differentiate between the geographical-topological determination of borders and the historical-cultural dimension (Haller, 1988). A topological determination refers first of all to a territorial unit, which is separated from adjacent territories by ...