![]()

THREE

Improvement for some: poverty and social exclusion among older people and pensioners

Demi Patsios

Broader policy and research context

Research into older people and pensioners1 has garnered a lot of academic and policy attention during the past decade. There are of course good reasons for this. From a demographic or population ageing perspective the sheer number of older people in the UK is at the highest level it has ever been in both absolute and relative terms. Estimates place the proportion of people aged 65 years or older at approximately 22% of the population which equates to roughly 13 million persons (ILC-UK, 2013). The number of pensioners has also increased dramatically last 20 years, with an estimated 26 million having reached state pension age (SPA).2 While longevity is a cause for celebration, it is also important to recognise that the UK’s rapidly ageing society offers a number of short- and long-term policy challenges (McKee, 2010). Although the main policy focus to date has been on care and pensions, great strides have been made in improving the financial situation of older people and pensioners, particularly those on lower incomes who are reliant on state pensions and other age- or disability-related benefits (for example, housing benefit, pension credit guarantee, council tax benefit, disability living allowance, carer’s allowance) to make ends meet. A lot has been written over the past decade or so regarding the generally improved economic, material and social position of pensioners and older people in the UK. At the time of the UK Poverty and Social Exclusion Survey 2012 (PSE-UK 2012), the proportion of pensioners living in low-income poverty was at the lowest level it had been for almost thirty years (MacInnes et al, 2013). Pensioners are now less likely to be in financial poverty than the majority of non-pensioners after housing costs (McKee, 2010). McKee goes on to suggest that although this progress should be welcomed, ‘much less progress has been made in helping those pensioners in more severe and persistent poverty’ (2010, p 20). In short, the poorest pensioners have fallen further behind middle-income pensioners, although inequality within most of the top half of the pensioner income distribution has changed little (Cribb et al, 2013). In addition, the measurement of social exclusion is a relatively recent endeavour, with little attention paid to older people (Price, 2008). Past studies of social exclusion have tended to focus on children, young people and families. However, research has emerged which suggests that older people might be more susceptible to social exclusion due to diminishing material and social resources, lower economic and social participation, and poorer outcomes in quality of life measured in terms of health and well-being, and deteriorating conditions in their living environment (Scharf et al, 2005; Barnes et al, 2006; Patsios, 2006; Becker and Boreham, 2009; Kneale, 2012). For example, Becker and Boreham’s (2009) study showed that 50% of all those aged 60 and older experienced multiple risk markers of social exclusion as found in Bristol Social Exclusion Matrix (B-SEM) (such as, poor access to services and to transport, were physically inactive, had a fear of their local area after dark, had low social support, and had poor general and emotional health). The older old (aged 80 years and over)3 are more likely to experience multiple risk markers than their younger counterparts. Taken together, much is known separately about how poverty and social exclusion affects – and is experienced by – older people, but very few studies exist which are able to look simultaneously at both as well as key differences between and within pensioner households using a large nationally representative sample of older people.

Overview of the chapter

This chapter adds to the rapidly evolving evidence base of poverty and social exclusion among older people and pensioners by analysing data from the PSE-UK 2012 using the B-SEM conceptual model (Levitas et al, 2007). The sample size and B-SEM sub-themes available in the PSE-UK 2012 provide a unique opportunity to look more closely at the relationship between poverty and social exclusion and how it affects the situation of a broad group of older people living in different pensioner household types. Each section begins with an overview of key literature/themes, followed by findings from the PSE-UK 2012. The chapter concludes with a discussion of key findings and implications for further policy.

Resources

Having adequate material, economic and social resources is central to personal well-being and these resources are important elements in understanding poverty and social exclusion among older people. According to Zaidi, ‘while social exclusion for older people can take many forms, being excluded from material resources is the key initial catalyst, which either starts the process of involuntary detachment from participation in society or serves as the identifier for other forms of social exclusion’ (2011, p 2). Lack of income and an inability to afford the types of goods and services that most people in a society have access to or to participate in common social activities figure centrally in exclusion from material and economic resources in B-SEM. Access to affordable and adequate public and private services, and community-based health and social services is a key resource older adults can draw on in order to live independently and well in their own homes. Social networks and social support are also key components of older people’s social resources, and when these informal networks are lacking (or weak) this can result in isolation, loneliness, poor health and well-being, less satisfaction with relationships and lower overall satisfaction with life.

Material and economic resources

Low income (at-risk-of-poverty)

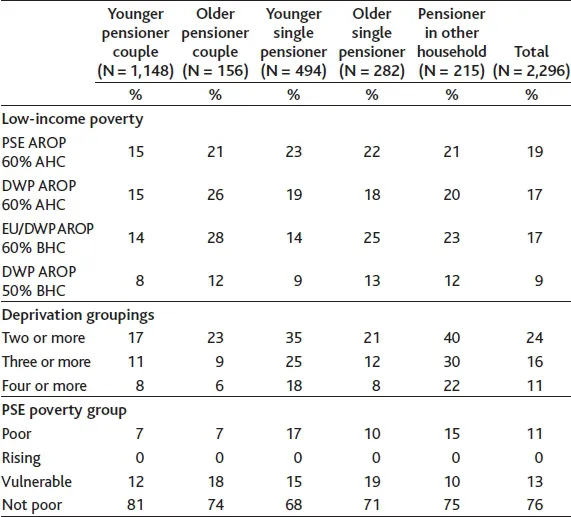

Low-income poverty is defined as people living in households with income below 60% of the median for that year. The UK government’s preferred measure of low income for pensioners is based on equivalised incomes measured after housing costs (AHC), as around three quarters of pensioners own their own home (DWP, 2013a). Considering pensioners’ incomes compared to others after deducting housing costs allows for more meaningful comparisons of income between working-age people and pensioners, and for pensioners over time (DWP, 2013a). The PSE-UK 2012 findings show that relative low-income poverty varies according to older adults living in various pensioner household types, as well as the poverty measure used (see ‘Low-income poverty’ in Table 3.1). Across the various low-income measures, younger pensioner couples are least likely to be at-risk-of-poverty (AROP), whereas single pensioners (younger and older, as well as pensioners living in other households) are relatively more likely to be AROP according to PSE and Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) AHC measures. Before housing costs (BHC) measures fall only slightly below AHC measures across households.

Material deprivation

McKay (2010) argues that low-income (households below average income – HBAI) figures are good for measuring changes over time, but do not necessarily reflect the multidimensional nature of poverty. As such, it is better to look at more ‘indirect’ measures of poverty. The DWP measures material deprivation among people aged 65 using the Family Resources Survey (FRS)4 and estimates have been included in the HBAI report since 2011 (DWP, 2013b). However, material deprivation is not officially used in government pensioner poverty reduction targets (such as those found in the Child Poverty Act 2010) or as an official means test for allocation of benefits. HBAI figures leading up the PSE-UK 2012 showed that the percentage of those in material deprivation fell from 9% in 2010/11 to 8% in 2011/12 (DWP, 2013b). In contrast, the PSE-UK 2012 uses a final validated set of 22 items and activities in the PSE adult deprivation index (see chapter one for an overview). Overall, one out of four older adults report material deprivation on two or more items and activities, one out of six report three or more deprivations, and approximately one in ten report four or more deprivations (see ‘Deprivation groupings’ in Table 3.1). Findings also reveal differences in deprivation grouping by pensioner household type. Older adults in other household types and younger single pensioners are twice as likely to report all three deprivation groupings. Older adults in couple households are least likely to report three or more or four or more deprivations, however, older pensioner couples are more likely than younger pensioner couples to report two or more deprivations.

Low income and material deprivation

Past research suggests that low income does not automatically result in a pensioner living in material deprivation (Bartlett et al, 2013), with some pensioners managing well on a low income (Kotecha et al, 2013). Analyses of FRS data show that only 2% of older people are in both relative poverty and material deprivation (Bartlett et al, 2013). PSE-UK 2012 analysis confirms that there is little overlap (3%) between low income and three or more material deprivations.

PSE poverty measure: combined low income and material deprivation

In the PSE-UK 2012, two main poverty measures, which combined equivalised household income and number of deprivations, were created: poverty group (poor, rising, vulnerable, not poor) and poor group (poor vs. not poor) (see chapter one for an overview of how the poverty measures were constructed). Older adults in pensioner households are less than half as likely to be poor as adults in non-pensioner households according to the main PSE measure. Findings also show that PSE poverty group varies both between and within pensioner household types, particularly when gender is considered. Younger single pensioners (17%) and older adults in other households (15%) are most likely to be poor, whereas younger and older pensioner couples are more likely to be vulnerable to poverty (that is, to have an equivalised household income just above that used to allocate adults into different poverty groups) rather than poor (see ‘PSE poverty group’ in Table 3.1). Further analyses by gender reveal that younger single female pensioners are more likely to be poor than their male counterparts (20% compared with 13%) and that older single female pensioners are more likely to be poor compared with older single male pensioners (11% versus 8%), whereas the opposite is true for older women living in other households (14% of female pensioners compared with 17% of male pensioners).

Access to public and private services

Services for older people

The main focus of community-based health and social care services for older people is on promoting their independence and intervening early to prevent them from requiring long-term care and support or hospital admissions. Older people are the main users of health and social care services but sometimes services do not meet their needs, either because they are unaffordable, or unavailable or inadequate. In the PSE-UK 2012, persons 65 years of age and older (n = 1,806) were asked about a number of services for older persons5 and the extent to which they thought that the services were adequate or not (if they were used), and reasons for not using them. Over these five services the largest category is that older adults do not want to use the service or it is not relevant to them. Older single pensioners are relatively more likely to report using a chiropodist (51%), home help/home care (25%) and day centre/lunch clubs (20%) and that these services were adequate. Affordability and lack of availability also appear to be barriers to service use, particularly for younger single pensioners and for those living in other households. Single pensioners (younger and older) are relatively more likely to report that they use a chiropodist but that it is inadequate.

Social resources

Social support (affective and instrumental)

There are various types of informal social support, including emotional, informational and practical support. The amount of practical and emotional support available in times of need is a key indicator of an older adult’s social resources. Greater anticipated support (that is, the belief that others will provide assistance in the future if needed) is also associated with a deeper sense of meaning and personal well-being over time (Krause, 2007). The PSE-UK 2012 asked respondents how much support they would get in seven situations.6 Findings show that single pensioners (younger and older) are most likely to report that they would not receive any support for the practical and emotional items and pensioner couples (younger and older) are most likely to report at least some potential help (see ‘Potential support’ in Table 3.2).

Social networks: frequency and quality of contact with family members/friends

The frequency and quality of older people’s contact with their social networks is a key indicator of a person’s social resources. Social networks and relationships are central to maintaining good physical, mental health and overall well-being (Windle et al, 2011; Nicholson, 2012; Steptoe et al, 2013). Even weak social relationships, as long as they exist in some numbers, have been shown to influence older people’s well-being (Haines and Henderson, 2002). However, as people age their social networks or social ‘convoys’ contract due to retirement, separation...