![]()

PART

I

GENERAL ISSUES

![]()

Caste Status and Intellectual Development

John U. Ogbu

Pamela Stern

University of California, Berkeley

Social scientists have long observed that the racial stratification in the United States is organized along the principles of caste (Berreman, 1960, 1966; Davis, Gardner, & Gardner, 1965; Dollard, 1957; Lyman, 1973; Mack, 1968; Warner, 1965, 1970). In the 1970s, the first author of this chapter suggested that observed differences between Black and White Americans in cognitive development and IQ test scores could be explained by using the principle of caste organization (Ogbu, 1974, 1978). This was in response to the intensified nature-nurture debate that followed Jensen’s (1969, 1971, 1972, 1973) statements regarding the profound influence of genetics in the determination of IQ. This debate continues to underlie much of the current research on intellectual development (cf. Benasich & Brooks-Gunn, 1996; Bouchard, 1997; Brody & Stoneman, 1992; Brooks-Gunn, Klebanov, & Duncan, 1996; Loehlin, Horn, & Willerman, 1997; Singh, 1996).

We remain dissatisfied with the conventional nature-nurture debate for three reasons. First, it is a debate with no possible resolution. Second, it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate White American beliefs about Black American intelligence from the “scientific theories” of differences in Black and White intelligence or IQ test scores. And finally, cross-cultural research increasingly casts doubt on both genetic and environmental explanations, but especially on the genetic explanation.

For these reasons, Ogbu offered the hypothesis that Black-White differences in IQ are due to different cognitive requirements of their respective positions or different ecocultural niches under an American caste system. The ascribed status of Black Americans (as a pariah caste), which until recently excluded most from participating fully in American technology, economy, and other institutions, also prevented Black Americans from developing to the same extent some of the cognitive or intellectual skills enhanced by the technological, economic, and other opportunities open to White Americans (Ogbu, 1974). Because IQ tests consist of the types of skills valued and promoted by middle-class, White culture, the scores of Blacks and other caste-like minorities tend to fall below the means of those in the majority. A cross-cultural study of caste-like minorities in six societies demonstrated that minority status rather than race was the critical factor in predicting IQ test scores. Across cultures, the caste-like minorities had lower IQ test scores than the dominant group both when the pariah caste and the dominant caste belong to the same race and when they belonged to different races (Ogbu, 1978).

Although some psychologists have taken note of our hypothesis (Herrnstein & Murray, 1994; Jensen, 1994; Neisser et al., 1996), no one has undertaken to test it. One difficulty we face in writing this chapter is the tendency of other researchers to confound caste with socioeconomic status. Consequently, one of our objectives is to clarify the difference between caste stratification and class stratification. Another objective is to discuss the social effects of caste positioning to the intellectual development of Black Americans.

The chapter is divided into six main sections: the relationship between intelligence and IQ; amplifiers of intelligence or origins of intellectual skills in a population; distinctions between caste, class, racial stratification, and minority statuses; Caste status, cognitive development, and IQ; the case of Black Americans; conclusions.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INTELLIGENCE AND IQ

Conventional Definitions

A cursory examination of the psychological literature on the subject of intelligence and IQ might lead the naïve reader to conclude that there is little consensus among psychologists regarding what is meant by intelligence. This view, however, is somewhat erroneous. Although psychologists cannot agree as to what intelligence or IQ means, there is an overarching belief that the two are synonymous (Helms, 1992). Some, like Jensen (1969), consider IQ to be a technical term to label whatever intelligence tests test. To others, IQ reflects the “global ability to absorb complex information, or grasp and manipulate abstract concepts” (Travers, 1982, p. 235). Still other psychologists define intelligence as information processing (i.e., how people interpret or process the information they receive; Kyllonen, 1994). One thing that students of intelligence of virtually all persuasions agree on is that it can be measured. So, when they refer to intelligence they mean IQ, which is what they measure. As Jensen (1969) put it, “intelligence (i.e., IQ) is what intelligence tests test” (p. 5).

An Alternative “Intelligence”?

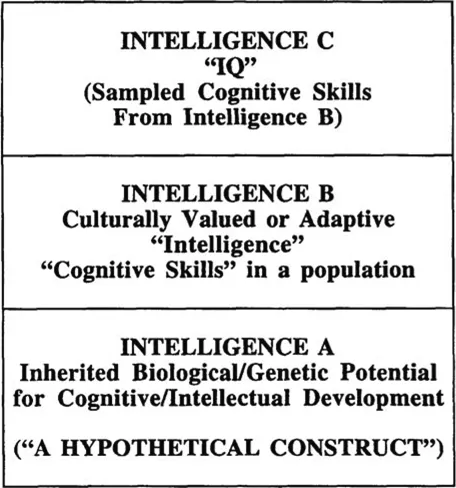

We propose an alternative definition of intelligence partly on the basis of suggestions from Baumrind (1972), Vernon (1969), and Greenfield (1998).1 From a cross-cultural perspective, intelligence is a cultural system of thought, a cultural or group’s repertoire of adaptive intellectual (or cognitive) skills. According to Vernon, there are three levels of intelligence: genotypic intelligence (Intelligence A), phenotypic intelligence (Intelligence B) and the intelligence measured by psychologists, IQ (Intelligence C). (See Fig. 1.1.)

Intelligence A, the genotype, is the innate capacity or potential (i.e., genetic endowment for intelligence) which individuals inherit from their parents. Intelligence A determines the level of intellectual abilities possible for individuals under given conditions. Similarly, the genetic potential of a population, Intelligence A, determines the extent of the intellectual skills of its members. Intelligence A is a hypothetical construct that cannot be directly observed or measured by psychologists, behavioral geneticists, or anyone. It only can be inferred or estimated from behavior, such as test scores (Jensen, 1994; Plomin, 1994; Vernon, 1969, p. 9; see also Ogbu, 1978, 1994a). What, we, following Vernon, also call Intelligence A is what Greenfield (1998, p. 81) chose to label panhuman genotypic intelligence. She defined it as the ability in all normal members of the human species to acquire competence in technology, linguistic communication, and social organization.

Intelligence B, the phenotype, is the observable behavioral manifestation of intelligence as defined in a culture. It refers to everyday observed behavior of an individual considered intelligent or not intelligent by members of his or her population. Intelligent behaviors reflect the adaptive repertoire of intellectual or cognitive skills in a population. Intelligence B is a product of both genetic potential (Intelligence A or nature) and environment. This is not the environment as defined in conventional environmental theory of IQ. Rather, environment consists of all social conditions and cultural activities in the ecocultural niche of a population that contribute to the intellectual skills of that population. Intelligence B is different for different populations partly because it is culturally defined and partly because it consists of intellectual skills adaptive to particular needs in each population’s particular ecocultural niche. For example, the kinds of behaviors considered intelligent, required, and valued in the ecocultural niche of White, middle-class Americans are somewhat different from behaviors required and valued as intelligent in the ecocultural niche of Igbo farmers of Nigeria or Inuit hunters in Canada. However, the extent and form of expression of Intelligence B in any population are determined by the same biological potential or Intelligence A, the panhuman genotype.

FIG. 1.1 Between phylogency and ontogeny: Genetic potential, cultural intelligence, and measured intelligence or IQ. Based on Vernon (1969) and Baumrind (1972).

On the basis of the first author’s experience, born to nonliterate parents in an Igbo village and now a professor at a major U.S. university, we accept Vernon’s (1969) claim that Intelligence B is not fixed. It changes when the ecocultural niche of an individual or population changes. The first author’s Intelligence B changed when he moved from his village and enrolled at a U.S. university. His experience is not unique. We are acquainted with many other individuals in similar and varying situations. Intelligence B of a population changes when its ecocultural niche changes. The introduction of formal, Western-style schooling is one type of this change. Employment by multinational manufacturing firms is another. What is important to bear in mind is that normal individuals and whole populations can and do acquire whatever intellectual skills are necessary because they possess the panhuman genotype (Greenfield, 1998).

Intelligence C, the IQ test scores or “Measured Intelligence, “ refers to a behavioral manifestation of intellectual skills selected from the adaptive intellectual skills of the White middle class. The selections are drawn from their specific Intelligence B. Intelligence C, IQ, is thus different from Intelligence B because it is only a part of the total intelligence of a population (White middle class, in this case). IQ also differs from intelligence because the intellectual skills included in IQ tests are selected for specific purposes, such as to predict academic achievement or job performance. The employment of IQ tests, in itself, is reflective of the social biases within a society, and IQ tests are often used to perpetuate social and economic inequalities (Fischer et al., 1996). In our view, IQ is NOT intelligence.

AMPLIFIERS OF INTELLIGENCE

Cultural Amplifiers

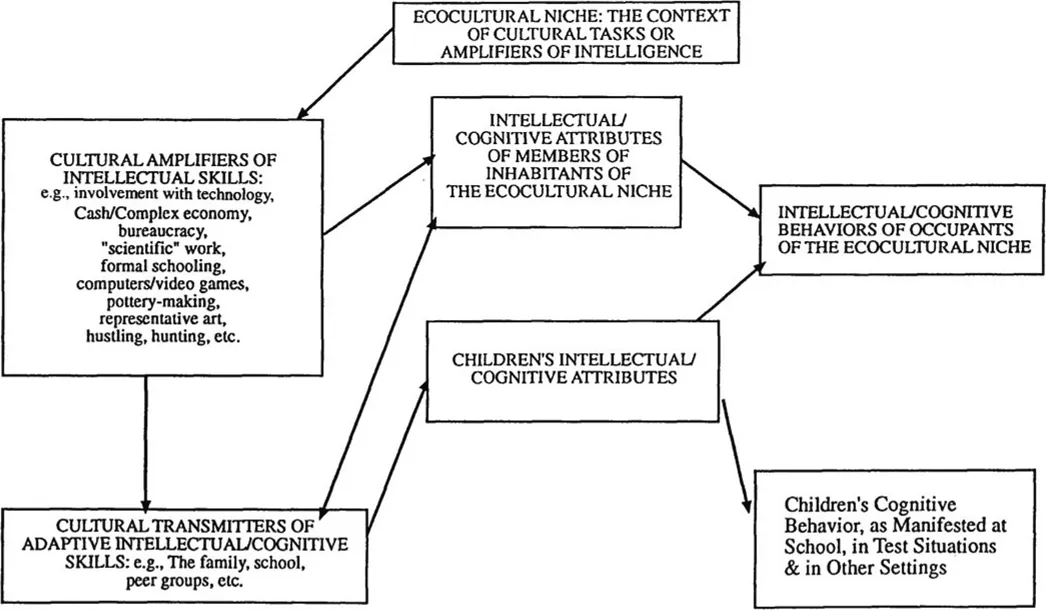

We designate as cultural amplifiers of intelligence activities or tasks in the ecocultural niche2 of a population which require and enhance intellectual skills. Cultural activities are amplifiers when they require, stimulate, increase, or expand the quantity, quality, and cultural values of adaptive intellectual skills (see Fig. 1.2). Some obvious cultural amplifiers in Western middle-class ecocultural niche include handling technology, participation in a large-scale economy, negotiating bureaucracy, and urban life. These cultural activities require and enhance intellectual skills such as abstract thinking, conceptualization, grasping relations, and symbolic thinking that permeate other aspects of life (Vernon, 1969). Each ecocultural niche presents a wide array of cultural amplifiers of the intellectual skills that are required for success in that particular niche. Different ecocultural niches requires different repertoires of intellectual skills. Some skills enhanced by activities specific to one niche may also be of value in other ecocultural niches. Other examples of cultural amplifiers and the associated intellectual skills found in various ecocultural niches are pottery making-conservation (Price-Williams, 1961; Price-Williams, Gordon, & Ramirez, 1969), market trading-mathematics (Posner, 1982; Saxe & Posner, 1983), foraging-spatial perception (Dasen, 1974); video games-spatial perception (Greenfield, 1998); and verbal games-verbal abilities (Foster, 1974; Hannerz, 1969).

FIG. 12. Origins of intelligence-cognitive skills. Based on Ogbu (1978) and Whiting (1963).

Cross-cultural studies of cultural amplifiers of intelligence suggest at least two conclusions. First, intellectual skills prevalent or considered important are not the same in all populations. They depend on the cultural amplifiers in the ecocultural niche. Second, normal members of all human populations can acquire new intellectual skills, including those included in IQ tests because all normal human beings possess the panhuman genotypic ability to do so. We observe this capability when individuals enter new ecocultural niches through migration, when formal Western schooling is introduced, and when social and economic circumstances change.

Commerce and Mathematical Skills. We might expect mathematical skills to be more prevalent and valued in a society whose economy is based on commerce than in a subsistence farming society. A comparative study of two West African communities found this to be the case (Posner, 1982; Saxe & Posner, 1983). The children of Dioula, a merchant population, had many opportunities through practice and observation to acquire mathematical skills whereas the children of the Baoule, an agricultural people, did not. Not surprisingly, when tested, Dioula children—even those who had not had Western-type schooling—performed better than Baoule children in tests of mathematical skills.

Video Games and Spatial Perception. Video games require...